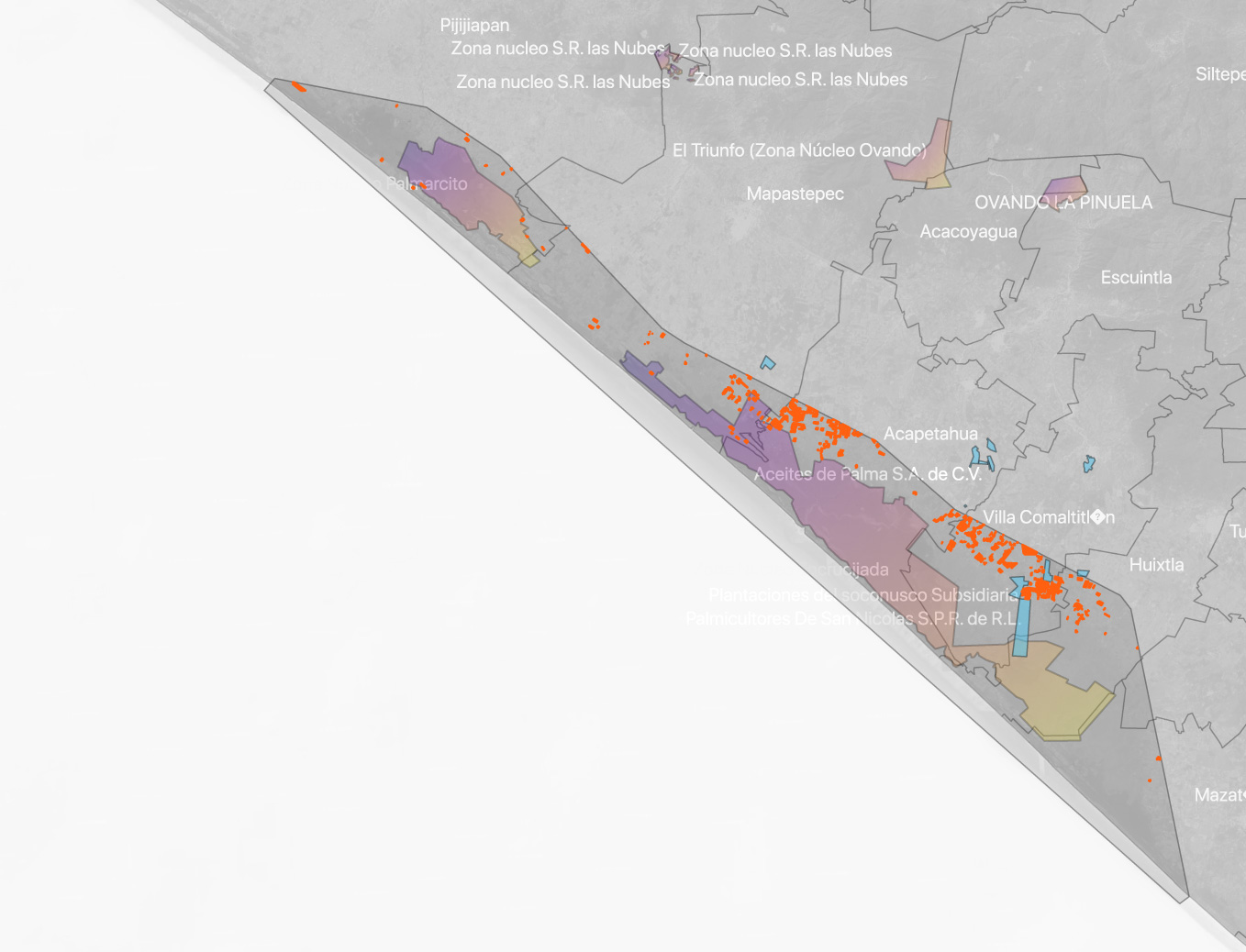

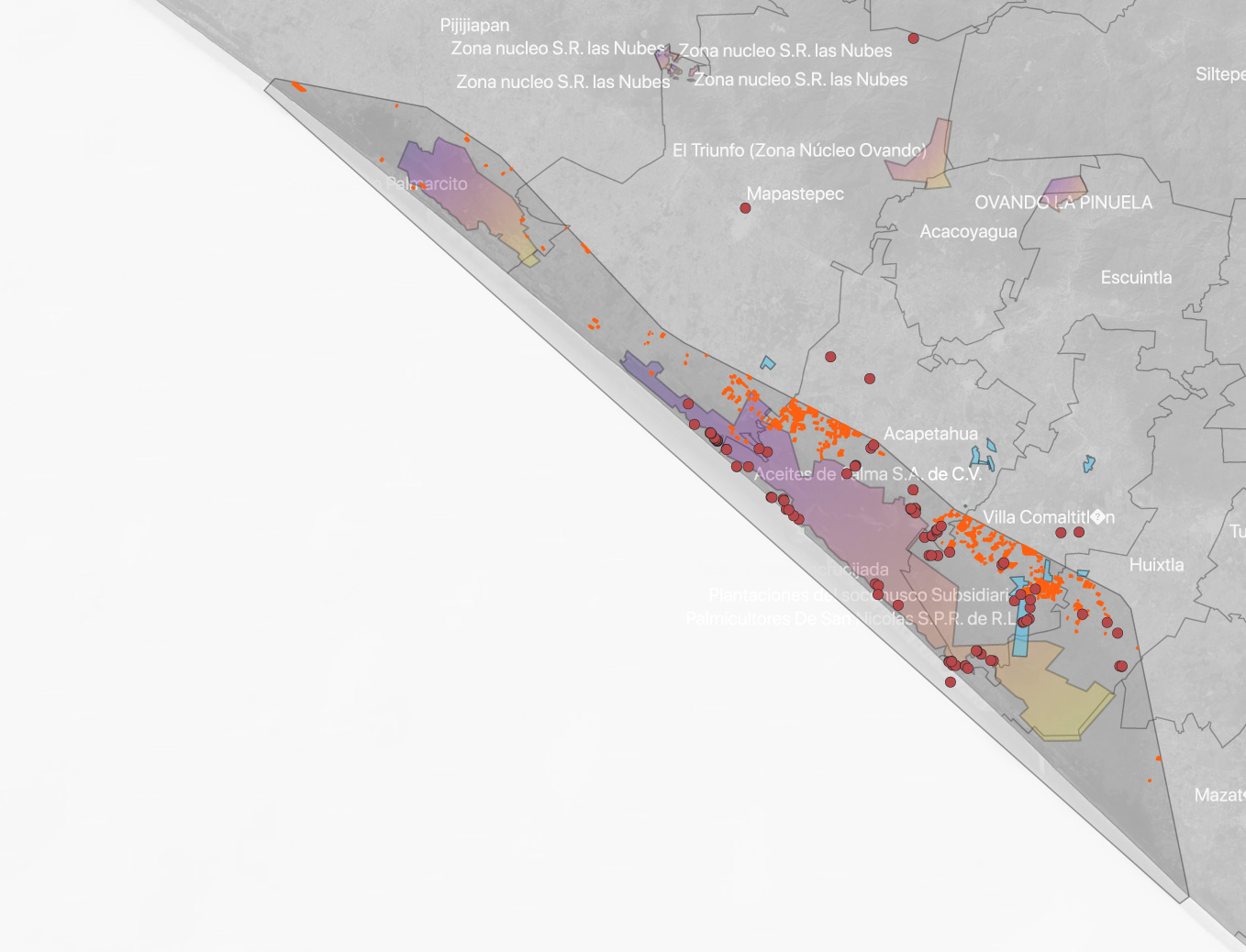

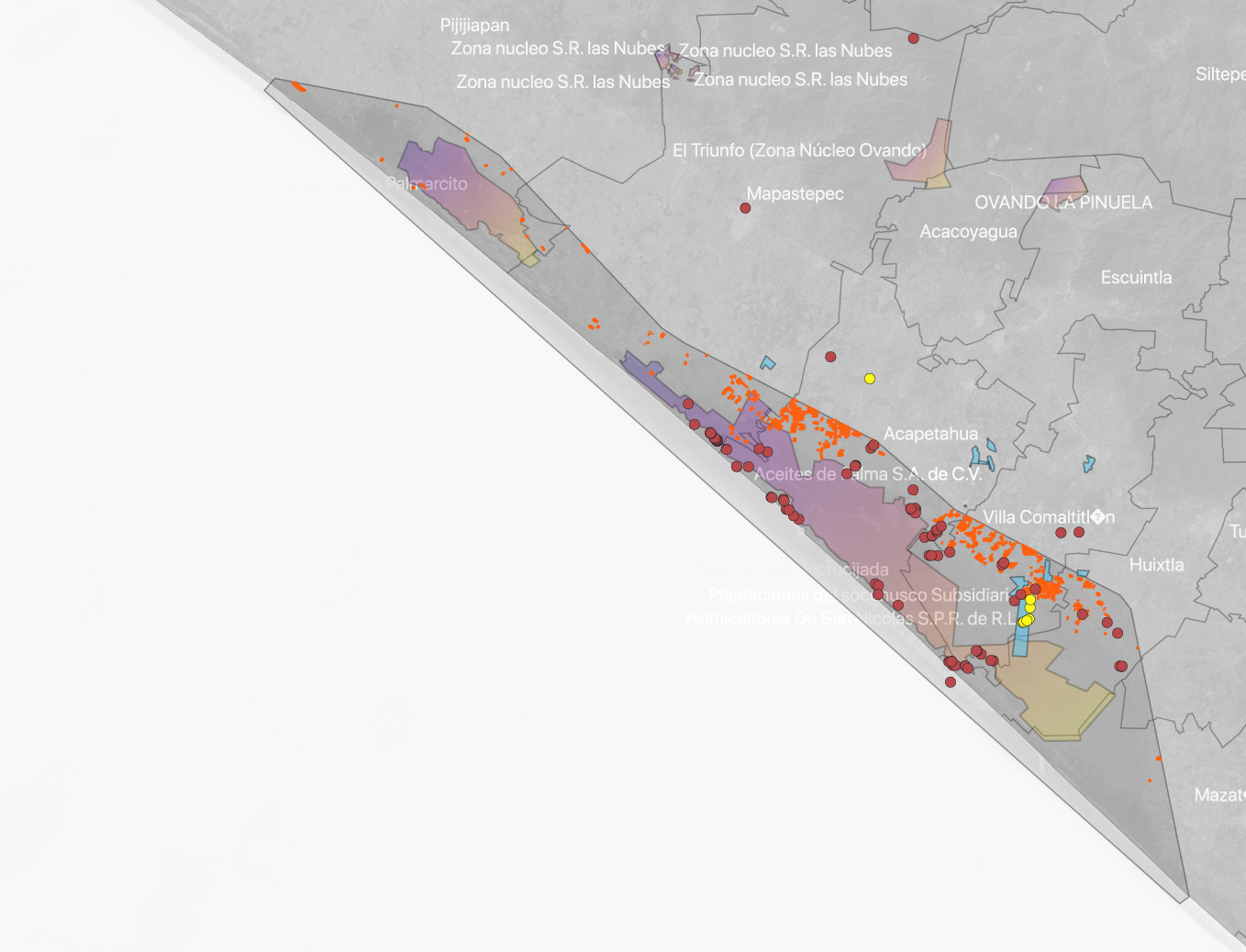

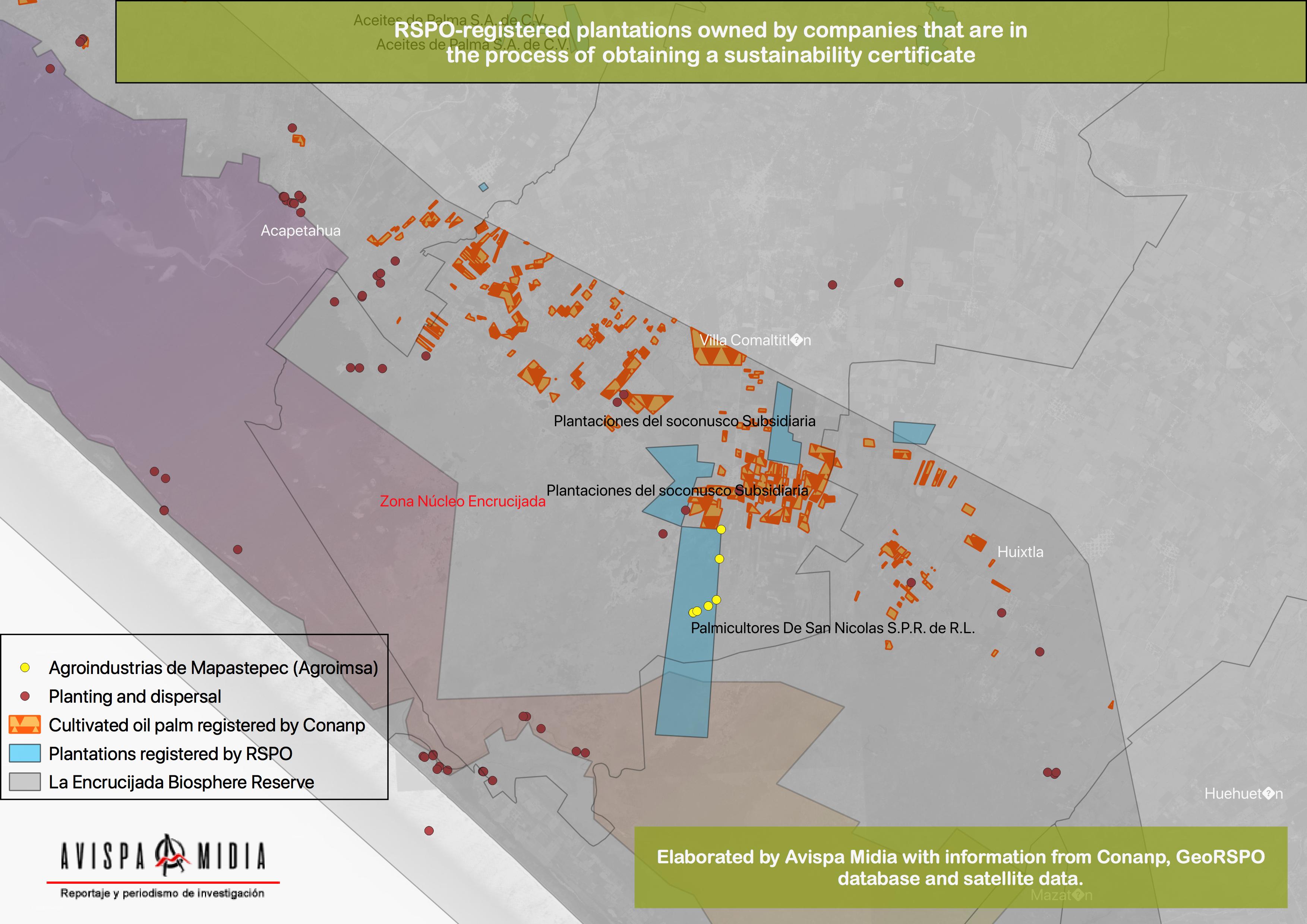

One of the reports provided by the CONANP, created for the Endangered Species Conservation Program (PROCER), mentioned that the expansion of palm cultivation is due to changes in land use, above all in “areas of high conservation value” in the reserve’s interior.

Pronatura Sur, the organization that authored this document, stated that to ready the area for palm planting, drainage structures were opened to regulate the excess water and maintain adequate conditions for developing the plantations.

According to the Management Plan, economic uses of the forest and land use changes within the REBIEN are prohibited without authorization from the Ministry of the Environment and Natural Resources (SEMARNAT). Avispa Midia made an information access request for records of the authorizations issued within the last decade. The agency responded that “no authorizations issued by this body were found regarding changes in land use in forest areas located in La Encrucijada Biosphere Reserve in the state of Chiapas.”

-

Palm fruit is transported to strategically located storage facilities like the one in Matamoros ejido in the municipality of Acapetahua, close to the REBIEN’s buffer zone. Photo: Aldo Santiago

-

The Oleopalma processing plant located in REBIEN's zone of influence obtains supplies from the two municipalities with the highest production at the national level. Photo: Santiago Navarro F.

-

A boy travels the road from his community, in the Nicolás Bravo ejido, to the Oleopalma processing plant in the municipality of Mapastepec. Photo: Aldo Santiago.

-

Between 2007 and 2012, the government of Chiapas distributed 4 million plants without supervising where they would be grown. At that time, plantations expanded in the coastal region. Photo: Santiago Navarro F.

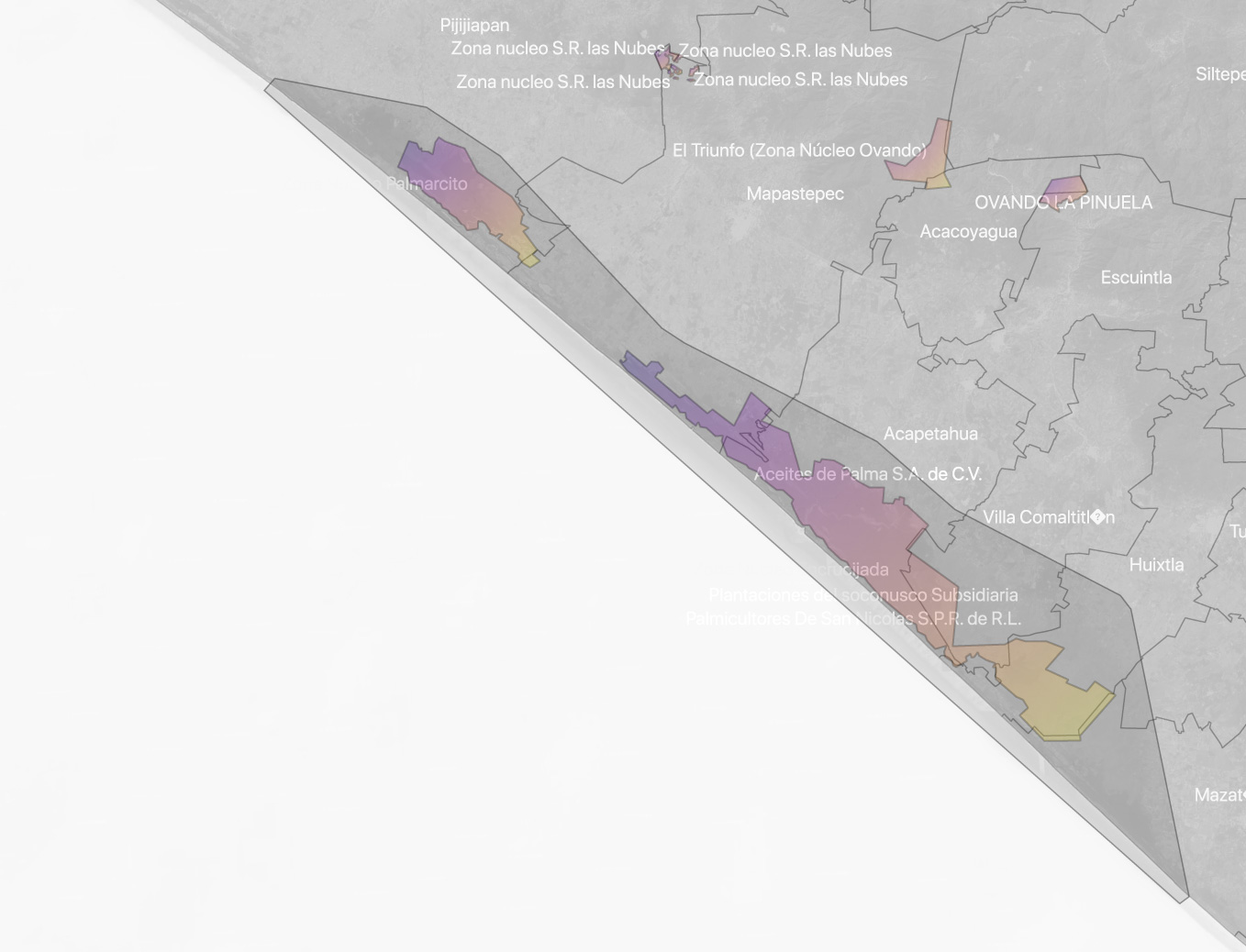

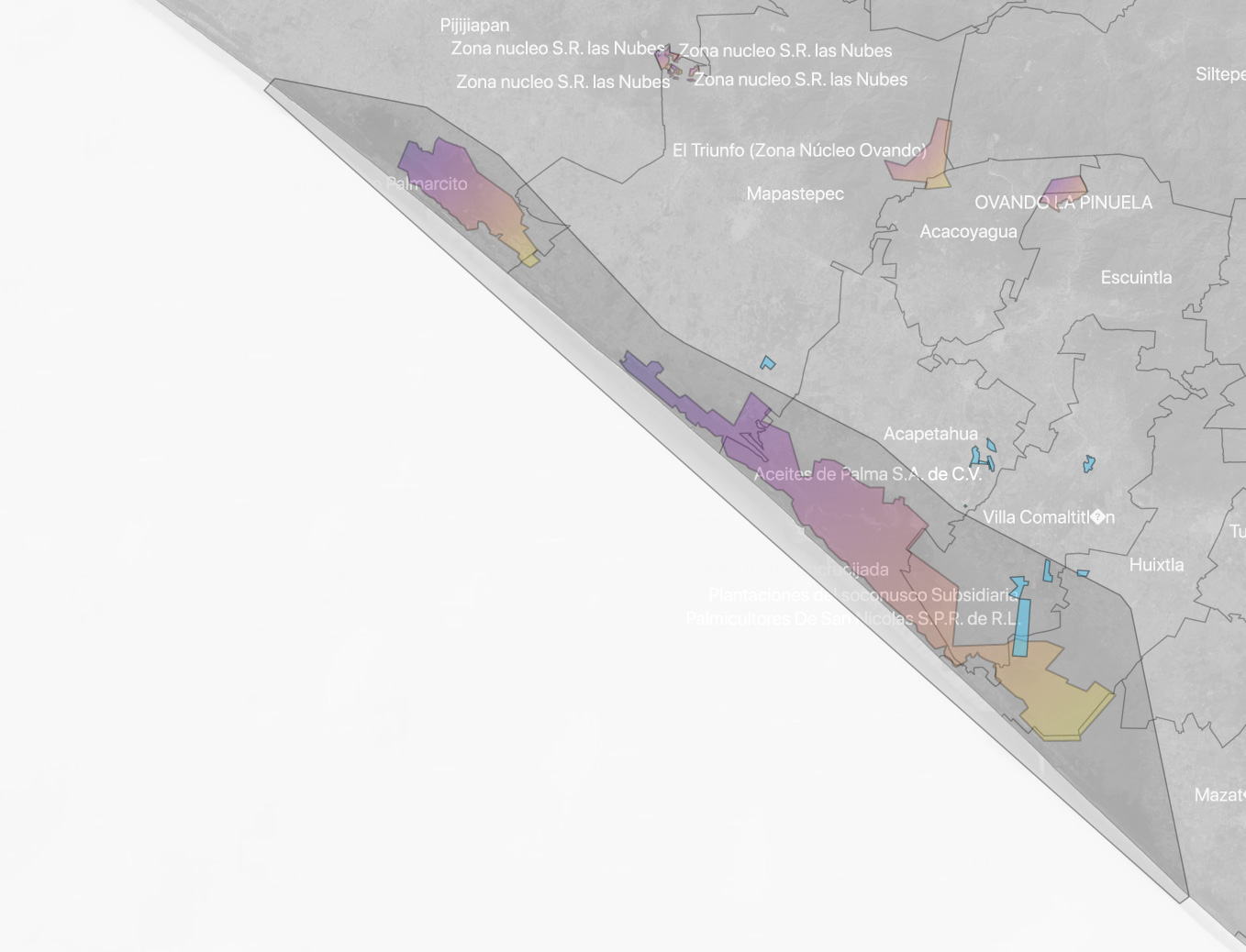

The CONANP and the SEMARNAT attribute the problem of the spread of palm to poor control by producers, so they have looked for strategies to legalize it. In October 2015, they presented the Preliminary Supportive Study for the Modification of the Declaration of 1995 of the REBIEN, which sought to remove areas where there are crops, livestock, and fisheries from the reserve.

Both agencies wanted to reduce the size of the reserve in order to regulate oil palm, arguing that “the goal is to adapt zoning, in particular incorporating areas with well-conserved ecosystems into the core zones, and removing areas where agricultural, ranching, and fishing activities are conducted,” as the document Avispa Midia had access to states.

They sought to remove an area of 8,345 acres (3,377 ha), of which 1,841 (745 ha) belong to El Palmarcito Core Zone and 6,504 acres (2,632 ha) to La Encrucijada Core Zone. This proposal never moved forward.

According to the LGEEPA’s regulations regarding Protected Natural Areas, the next step to continue with the proposal for modification of the reserve is publication of a preliminary study for public consult, before proposing modification to the federal executive branch. This did not happen.

Castro said that the families that grow and depend on palm are very visible because they’re already involved in several positions within the production chain, not only as growers, but also transport or processing plant workers. “There’s already an economy with a certain strength around African palm in the region,” he said. Furthermore, he said that he can’t enforce, because “it would create a much wider conflict, socially and economically.”

In 2016, the National Human Rights Commission (CNDH) issued General Recommendation 26/2016, for addressing impacts on protected natural areas and human rights. It highlighted the degradation of the REBIEN, explaining that for several years, the reserve has faced “the use of these lands for the establishment of oil palm plantations.”

That same year, instead of going after the plantations, CONANP hired the nonprofit organization Naturaleza y Redes A.C. to run a project called Strengthening African palm control strategy in the REBIEN, which only focused on the problem of seed spread. Information gathered through this project helped to eradicate and control individual oil palm trees covering 28.4 acres (11.5 ha) inside the reserve.

Poulette Hernández, co-founder of the Digna Ochoa Human Rights Center, clarified that this is no easy task. She explained that people are mistaken in thinking that palm is like any other tree that can be disposed of by being cut down and burned. Castro agrees that eradicating this crop is not simple. He explained that palm trees can’t be cut down with a machete, and even doing it with a chainsaw is very complicated. What’s more, all of the brush must be removed from the site, since it can contaminate the mangroves.

The CONANP has a publicly available record of the January 2020 eviction of what the agency considered to be two incursions of people who, they say, threatened the buffer zone and core zone of the reserve. Castro stated that they recovered 2,251 acres (911 ha) that had been impacted by filling, removal of vegetation, and the introduction of exotic species like oil palm.