Alberto Villatoro, a farmer in the fertile region of Los Cacaos in Chiapas, Mexico, recalls, with a mixture of sadness and anger, how innocently he used to walk over the area's silvery blue rocks.

"I can remember those metals in the river ever since I was a child," he told Truthout. "We would kick them around on the paths, unaware that it was titanium."

Now those same rocks have become highly sought after, and the Chinese mining company Honour Up Trading is seeking to gain control of large swaths of land in Villatoro's community to exploit one of the biggest seams of titanium in Mexico. "We've already had open-pit titanium mining here [in 2009]. Now they want to build the tunnel and leave us living on land resembling an eggshell," he said. "That would be the end of our shared land."

Mexico's government gave the green light for titanium mining to occur below 500 of the 530 hectares that make up the Los Cacaos community, via underground tunnels stretching from the foothills of the Sierra Madre mountain range up to the upper section of the town.

Villatoro and his neighbors in Los Cacaos express acute fears about the potential environmental effects of Honour Up Trading's plans. "If they build tunnels, the mountain will collapse, because it is a very wet area," Villatoro told Truthout. He believes that local leaders "were tricked into signing off on the exploration process" by the mining company, he added.

Florentina Antonio Morales, a local farmer echoed this allegation. "They came here to trick us, that's the truth," she told Truthout. "They promised us a lot. They said they would build a market, a road, a park for the kids. But none of that went any further than just talk."

The company even went so far as distributing food to gain the support of the community, Morales added. "They give the authorities a bit of money and they trick the people with a food store, like the government does," she said. "I honestly have no need for a food store; I grow my cacao and my coffee ... They are affecting our harvest, our health and our animals' health."

Residents of Los Cacaos are also alarmed about the prospect of increased titanium mining due to its damaging health effects. According to data from the REMA organization, in Mexico's Soconusco region, cases of liver, stomach and testicular cancer are five times higher than average in the Acacoyagua municipality where Los Cacaos is located and where two titanium mines are in operation. Some of the cancer cases have occurred in children. In addition, people who have bathed in the Cacaluta, Doña María and Cintalapa rivers, into which residues from the mines flow, have developed skin rashes and sores.

The increased pollution of the waters in Los Cacaos could affect many other communities as well because the abundant water from that region supplies other communities in the foothills of the Sierra Madre mountain range.

The Undermining of Los Cacaos' Democratic Process

The Los Cacaos community is an ejido, a rural, collectively farmed property. It is one of the distinctive agrarian hubs that still remain as a result of the Mexican Revolution of 1910. "An ejido is a communion of between 100 and 200 people who equitably possess a part of land," explained Villatoro, one of the ejido members. "It is not a piece of property. Ejidos are governed by majority rule, and to that end we make use of assemblies. There is a commission that represents everyone, but the assembly is the highest authority. The commission ensures that what is decided in the assembly actually takes place."

Villatoro said there were irregularities in the convening of the assembly and the formation of the agreement in which the mining project was approved. "They did not meet the requirements of the Agrarian Law," he said. "There were not enough signatures of ejido members that are legally registered on the national agrarian register, and this means those that signed are falling into an irregularity." Furthermore, he added, "on the day the assembly was held, the authorities said that the mining would last for one year. When they brought along the signed agreement, we saw that it was really for 50 years. The ejido authorities had already sold themselves to the company, and many people do not speak out due to fear."

Gustavo Castro Soto, a researcher from the Otros Mundos (Other Worlds) civil association, told Truthout that "what we are seeing is that the companies have started to use a pattern with communities: dividing them. They divide, buy, employ all sorts of pressure and extortion. This happens with all the extractive projects in the country, which has created a range of conflicts."

The contract that grants the El Puntal SA mining group permission to extract minerals from the Los Cacaos ejido stipulates that "the ejido and the beneficiary agree on a payment of 500,000 pesos for the fulfillment of this contract ... as well as a bonus of US$5 per ton extracted." It adds that "plots which contain minerals will have to be negotiated in private with the owner of said plot." The contract also stipulates that a "pay bonus of US$2 per ton extracted" would be paid to the landowner.

These sums of money offered on behalf of the exploitation of minerals are far too small to cover the negative impacts of mining. Moreover, the individualized nature of the contracts threatens the very form of organization specific to the ejidos, which traditionally make decisions that affect the community as a whole through assemblies. Individual negotiations are the reason why communities are divided and internal confrontations are created. Dividing communities through the negotiation of individual contracts is a strategy used in most extractive contracts carried out in Mexico.

An official evaluation published by Mexico's own Environment and Natural Resources Ministry admitted that the mining project in Los Cacaos threatens a region of high biodiversity and ecological importance, but the ministry nevertheless signed off on the project.

Meanwhile, the Environment and Natural History Ministry of Chiapas published its own evaluation of the mining project in September 2014 and issued this damning opinion: "The project entitled 'casas viejas mining project,' to be carried out in the Acacoyagua municipality, is deemed unfavorable given that the carrying out of said actions would cause irreversible damage to the environment."

Federal authorities ignored this technical evaluation

In the context of free trade agreements, governments have an obligation to guarantee foreign investments or face being sued in the World Bank's International Center for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID), where investment disputes between companies and nation-states are resolved.

"If governments do not guarantee investments, they are accused of indirect expropriation," Soto said. "This condition barely receives a mention. Many multinational companies have sued governments because of laws that hinder investments or because the governments withdraw concessions. There are studies which show that 60 percent of company lawsuits in the ICSID come from the mining industry."

Governments therefore have to adapt laws within their legal framework in order to facilitate investments. "Before the free trade agreement, for example, 52 percent of land in Mexico was communal property," Soto added. "Over half the land area and its riches, such as gas, oil, gold, water and wood, was in the hands of the poor. With the package of structural reforms that the government has been promoting, the land of indigenous people and farmers is being privatized so that international investments can force their way in."

The Case of La Joya

The El Triunfo community in the Escuintla municipality of Chiapas is facing similar problems as Los Cacaos. Honour Up Trading was issued a concession in La Joya, within the community of El Triunfo, which manages and owns the land collectively as an ejido. Established in 2013, the concession would last until 2063.

"We had never had problems with cancer in our communities before, but now there have been many recorded cases since the mines began operating," Paula Velázquez, a health volunteer in Independencia, told Truthout. "Young pregnant women are now having fetal deformities, and miscarriages too. Animals are already dying. That's why we don't want the mines."

Francisco Bautista Hernández, secretary of the ejido committee of the Independencia community in Escuitla, told Truthout, "The government gives out the concessions with no concern for the well-being of human beings, nature or animals. We haven't received any information."

Independencia's ejido is arguably the most well organized town in the region. The community and its leaders are against mining. They have filed complaints on many occasions, mainly against the owners of the La Joya mine. Other communities are less vocal. At least three other mining concessions of a greater size in the same area that border on the La Joya project are, for the time being, keeping quiet.

The mining concessions form a continuous line along Chiapas' Sierra Madre mountain range, which indicates the existence of a large vein of titanium primarily in the whole strip. A huge number of streams and rivers run down along the entire length of the range, which are used by the communities to drink, bathe in and irrigate their crops. "We don't want them to destroy the Sierra Madre because we have lots of vegetation and water," Bautista said. "We have two streams that will be polluted if mining takes place; lots of disease, and human and animal deaths will arrive."

In May 2015, the Civil Protection Ministry for Integrated Disaster Risk Management in the state of Chiapas evaluated the region surrounding the La Joya mine as being at "high risk" of problems resulting from the mine. Nevertheless, the concession was awarded to Honour Up Trading by the federal government.

Gustavo Castro, who is following the process in the region, said the mining company used bribery to get members of the El Triunfo ejido to accept the project. "The ejido members had reached an assembly decision to safeguard the ejido from mining, but the company arrived in late 2014 and offered them $1,000 for each ejido member's vote, and that was when they gave in," he said.

The Global Imperative Behind Mining in Chiapas

The push to increase titanium mining in Chiapas is part of a global response to the demand for titanium created by the increasing popularity of laptops and mobile phones, which require titanium to produce.

Hans Vestberg, the executive director of Ericsson, predicted in 2012 that by the year 2020 there would be 50 billion mobile phones connected. Manufacturing a single mobile phone requires at least 200 types of metals, including titanium.

Titanium is also used in the weapons, aeronautical, naval and nuclear engineering industries and is heavily sought after by the United States, the European Union, Japan and China.

Mexico is one of five Latin American countries where the presence of the material has been identified, along with Brazil, Paraguay, Chile and Peru. Mexico's Finance Ministry maintains that the country could meet a significant part of the world's demand for titanium, pointing to deposits in the subsoil of Chiapas.

According to the Mexican government's Comprehensive Mining Administration System (SIAM) and Infomex, 99 mining concessions have been granted by the federal government in the state of Chiapas in 2015, with operating licenses that are valid until 2050 and 2060. The peasant land and indigenous territory granted in concessions totals approximately 1,057,081 hectares, the equivalent of 14.2 percent of the state's area.

Otros Mundos' Gustavo Castro Soto said that in addition to these, there are also many other hectares still awaiting to be granted in concessions, given that there are minerals across the whole state. "There are also suspended concessions, inactive concessions and others that are in force, which does not mean they are currently being mined," he said. "We also know that there is a lot of illegal mining, not recorded on the state's books."

The concessions have primarily been awarded to four foreign companies, according to data from Otros Mundos. Three of them are Canadian: Linear Gold (now called Brigus Gold), BlackFire and Riverside Resources Inc. The fourth is the Chinese company most active in Los Cacaos: Honour Up Trading.

Environmental Impacts on Chiapas

The biodiversity and environmental importance of the Soconusco region in the southwest corner of Chiapas make the threat of mining particularly alarming. According to Soconusco's Regional Development Program, six uninterrupted wildlife reserves exist in the area: three state reserves (El Cabildo Amatal, El Gancho Murillo and Cordón Pico el Loro-Paxtal) and three federal reserves (La Encrucijada-Volcán, Tacaná and El Triunfo).

In La Encrucijada biosphere reserve, mangroves stretch up to 35 meters in height, making them the tallest mangroves in North and Central America. Studies carried out by the Frontera Sur College (ECOSUR) and the Chiapas State Institute of Ecology and Natural History have confirmed that there are 69 species of mammals and 23 families in eight orders in the reserve, located on the strip of mangrove forest along the state's coastal zone.

The Cordón Pico el Loro-Paxtal protected area is connected to the Mesoamerican Biological Corridor, which is traversed by endangered species such as the jaguar.

The El Triunfo reserve is home to 10 different types of ecosystems, including the globally threatened cloud forest, which allows water to return to the Sierra Madre Mountains.

Ongoing Resistance Against the Mines

Following dissent in the Soconusco region, where one of every three hectares has been awarded in concessions to the mining industry, local residents have carried out protests this year in nearly every community against the impacts of mining.

In September, residents of the Nueva Francia ejido in Escuintla, Soconusco, agreed to impede the operations of the El Bambú mining project, which is in charge of the Mazapa and El Puntal projects that have been mining titanium for more than eight years.

And in August, various municipalities decided to declare themselves "free from mining" in a communit

Close to 300 representatives from the municipalities of Tapachula, Huhuetán, Mazatán, Suchiapa, Tuxtla Gutiérrez, Acacoyagua, Escuintla, Cintalapa and Tonalá took that step due to the serious health effects that have become evident in the region.

Soto said, "We join ours to the 2,000-plus 'free from mining' declarations in the country, and to the 80-plus ejido agreements and communal lands, and the 30 municipalities of Guerrero, Oaxaca, Puebla and Chiapas whose inhabitants share the same position of 'no to mining!'"

Published in ⇒ Truthout.org

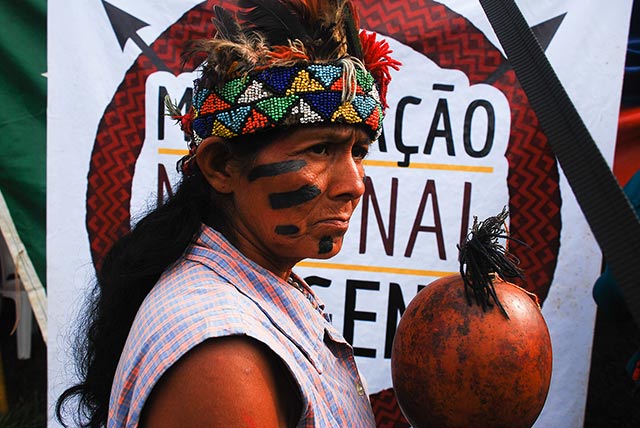

For four days and three nights, more than 1,500 indigenous individuals filled one of the gardens in front of the National Congress with colors, music and rituals. (Photo: Santiago Navarro F.)

For four days and three nights, more than 1,500 indigenous individuals filled one of the gardens in front of the National Congress with colors, music and rituals. (Photo: Santiago Navarro F.) Indigenous women leaders were also present for the taking of congress to denounce violations of human rights suffered by indigenous people. (Photo: Santiago Navarro F.)

Indigenous women leaders were also present for the taking of congress to denounce violations of human rights suffered by indigenous people. (Photo: Santiago Navarro F.) The military police were constantly present, protecting the headquarters of Brazil's three branches of government from the indigenous protesters. (Photo: Santiago Navarro F.)

The military police were constantly present, protecting the headquarters of Brazil's three branches of government from the indigenous protesters. (Photo: Santiago Navarro F.)