Indigenous leaders from the five regions of Brazil traveled for days to an encampment convoked by the Coordinating Body of Brazil's indigenous people (APIB), which took place from April 13 to 16 in the federal district in Brasilia. The district is both a geographical center and a center of power in Brazil, as it is where the three branches of government are headquartered.

For four days and three nights, more than 1,500 indigenous individuals filled one of the gardens in front of the National Congress with colors, music and rituals. Their principal objective was to put pressure on the three branches of government so that the proposed constitutional amendment No. 215 - better known as the PEC 215/2000 - is not passed. This amendment, among other things, would transfer the decision-making power of demarcation of indigenous territories to Brazil's legislative branch. Currently, this type of legal-political decision is in the hands of the executive branch.

Within Brazil's Congress, there is a faction known as the "Rural Legislators," a group of legislators who have transferred jurisdiction over private multinational companies to the legislative branch. Of the 50 members of Congress that make up the special commission that will review the proposed constitutional amendment, PEC 215/2000, at least 20 financed their electoral campaigns with support from big farming, mining and energy firms, as well as from the forestry sector and banks. Among the members of the Rural Legislators group is Agriculture Minister Katia Abreu, a business owner and fierce defender of big agriculture businesses. Another is Luis Carlos Heinze, one of the leaders of the group, who is also the president of the Parliamentary Farming Front (FPA). In 2014, a lawsuit was brought against him by indigenous organizations because he encouraged industrial farmers to use armed guards in order to forcibly remove indigenous people from their land.

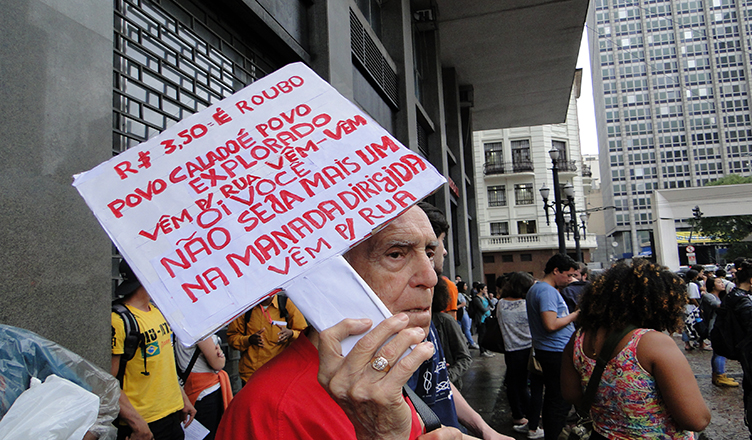

Those who attended the protest dressed in their traditional attire as leaders and sages of the community and painted their faces with vibrant vegetable-based paints of red, yellow and black. Some smoked tobacco; others prepared their bows and arrows. It was a moment to take to the streets and deliver a letter signed by all of the groups present at the encampment, addressed to President Dilma Rousseff, urging her to approve and sign a bill that is still within her power regarding 20 indigenous territories. They also reminded her of her commitment, expressed to indigenous groups during her presidential campaign in an open letter in 2014, where she pledged not to change the constitution and to move ahead with demarcating indigenous lands.

"During her presidential campaign, she [Dilma Rousseff] committed to demarcating indigenous territory in Brazil. Today, we see that indigenous people are moving toward complete disappearance," said Francisco da Silva, an indigenous Kapinawá leader from the state of Pernambuco. "If she herself does not honor her own words and the constitution, the only thing left for us to do is for us to demarcate our own territories and to defend our ancestral lands ourselves, because if we do nothing, this law will leave us in the hands of the multinational corporations."

While the encampment was underway in Brasilia, Rousseff was asked by various media outlets in an April 15 press conference about those who were protesting. Her response attempted to discredit the presence of the indigenous groups. She affirmed that the discussion regarding indigenous rights in her administration is "systematic," and stated that "there is no unified indigenous movement; the question regarding indigenous movements is not singular; it is diverse."

"Having declared that, [Rousseff] committed a grave error in her discourse, because we are here with representatives of the five regions of the country, with more than 200 different indigenous groups represented," said Sonia Guajajara, an indigenous woman from the state of Maranhao in northeast Brazil.

The military police were constantly present, protecting the headquarters of Brazil's three branches of government from the indigenous protesters. (Photo: Santiago Navarro F.)

Dried Up Dialogue

The indigenous leader Babau Tupinamba, leader of one of the best-organized groups in Brazil, who live with a high degree of self-sufficiency, readily affirmed that indigenous people need to prepare themselves for a more radical, even violent struggle. "I said in the Congress that we have returned to colonial times. And we, as the Tupinamba, the first people to confront the colonizers in the year 1500, today we call on all indigenous people to prepare themselves for a confrontation. And if it is necessary, we will even form a guerrilla force if this law is not rejected," he told Truthout.

Babau knows that his words carry a heavy weight and extreme responsibility, but argues that what is at risk are the lives of the indigenous people who are being assassinated by the owners of industrial farms. "We as indigenous people are pacifists; we have no desire to have a confrontation; we just want our lands. But with these types of decisions, they are pushing us to a point of rebellion. If we don't have another option and they continue like this - there are 102 proposals in Congress against indigenous people - we will have to form a guerrilla, because we are not going to let them force us off our ancestral lands; we refuse to leave. Because an indigenous person without land is no longer indigenous."

The PEC 215 bill is just one of the many violations of the human rights of indigenous people in Brazil. "There is no community right now that is not suffering the impacts of a capitalist project. Behind the impetus for this law are the interests of Monsanto, Nestlé, Syngenta, Cargill and other corporations that want to take our lands. They are the same ones that promote the killing of indigenous people," Rootsi Tsitna, an indigenous person from the state of Mato Grosso do Sul, told Truthout.

All indigenous groups have suffered violations of their human rights. "There are hundreds of projects in indigenous communities and none of them consulted the people. They are violating the 1988 constitution, which came at the cost of a lot of blood, and the United Nation's International Labor Convention 169, which establishes the requirement of previous consultation of indigenous people. We should not have to negotiate anything, because they are our lands and it is our right [to be here]," said da Silva, the indigenous man from Pernambuco.

Allies?

Not only indigenous groups worry about the PEC 215 bill. Organizations such as the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) have also expressed concern, since the amendment would also affect protected natural areas in the country. However, theirs contrasts with the position of several indigenous groups that have been affected by their politics. As an example, in 2011, the Maggi Group sold for the first time 85,000 tons of its "responsible soy," with the "green label" given by the WWF, through a program of "environmental certification" in collaboration with Bunge, Cargill, Monsanto, Nestlé, Syngenta, Unilever and other corporations that have been connected to the forcible removal of indigenous people from their lands in Brazil and various countries around the world.

Some political figures came to visit the indigenous encampment as supposed allies, such as ex-presidential candidate Marina Silva. She is an honorary member of the International Union for Nature Conservation (UICN) and a defender of the conservation policies promoted by the WWF and other nongovernmental organizations that promote national parks, natural protected areas, peace parks, cross-border parks, sanctuaries and green market policies such as carbon credits.

"There are many politicians who have come to talk with us, above all during election season, but all that we want is the demarcation of our territories," an indigenous Cayapo individual from the town of Xingu in Mato Grosso do Sul told Truthout. He argues that carbon credits are another way to remove them from their land. "We have seen the experiences of the Suruí people, who accepted the REDD and its carbon credits and conservation projects. They can no longer hunt, grow crops or use materials they need for celebrations and rituals," he said. "We know how to take care of nature because she is our mother and we don't want another carbon credit agreement, because it is just another way of removing us from our sacred lands."

At the encampment, indigenous Mundurukus denounce plans to build the biggest hydroelectric dam in Brazil on the Tapajós River, which would lead to the disappearance of the Munduruku people. The presence of armed forces has been the only signal of dialogue thus far. (Photo: Santiago Navarro F.)

Indian Day?

During the encampment, the indigenous leaders appeared in the House of Representatives and the Senate several times, not just to deliver their signed letter, but to express their discontent and their rage. The response was that PEC 215 will not be voted on, but neither will it be archived, which left the indigenous representatives unconvinced.

On the encampment's last day, April 16, Congress' doors were opened in a tribute to the indigenous representatives in honor of "Indian Day." Due to security issues, only 500 out of 700 in attendance were allowed entrance. The mayor did not attend the event.

Indigenous leader Marcos Xucuru expressed his anger and said that little should be expected of the government and political parties; what remains is the necessity of taking their land and assuming the consequences. "Our fight will continue and we are going to demarcate our lands ourselves. And if necessary, we will fight like the Tupinamba, who have confronted the federal police and the military and we will force them to leave our territory. As indigenous leaders, we are willing to give our lives for our Enchanted Ones - our ancestors - and for nature," Xucuru told Truthout.

Babau says that it is the government that will be held responsible if the genocide continues in his country. "We call upon all indigenous people all over the world, who are the only ones who understand us, to pay attention to what will happen. Because the government had the opportunity to negotiate with us, but the dialogue is drying up," he said. "We will offer our lives if necessary, but we will not let them take away our lands."

Published in ⇒ Truthout