By Renata Bessi

Cover photo: Maya Q’eqchi’ women on recuperated lands in Chapín Abajo. Photo: Santiago Navarro F

Lake Izabal is a sacred place for the Maya Q’eqchi’ people. The clear blue waters produce a mirror of nearly 600 square kilometers near the coast of the Caribbean Sea of Guatemala. All around the lake, the largest in the country, Maya Q’eqchi’ communities have lived since before the arrival of the Spanish.

From El Estor, the urban center at the north of the lake where there is also a military base, the Avispa Midia team traveled in a straight line toward the south shore of the lake. The journey was approximately two hours aboard a small boat conditioned to make collective trips to the community. During the rainy season, it is the only way of arriving to those territories. There, visitors are received with a monotonous olive-green landscape of extensive African oil palm plantations.

On this side of the lake there are 16 Maya Q’eqchi’ communities who have struggled to continue living in their territories, and to expand out from the tiny corner to which they have been subjected by extensive oil palm plantations belonging to the Naturaceites company. A second military detachment is also located there.

A few meters from the dock on the south side of the lake is Chapín Abajo. For at least three years this community has suffered the intensification of eviction attempts and violent military raids carrying out supposed arrest warrants of community members. During the raids, soldiers from the detachment on the northern part of the lake move around in speedboats for the “combat.”

The Maya Q’eqchi’ grandmother who identified herself as Juana painfully remembers in her mother tongue the last attack against the community. “I felt the roar of bullets behind my feet as I tried to protect the children. They treated us like animals,” she tells the Avispa team. The military raided Chapín Abajo on December 6, 2022, supposedly with 20 arrest warrants against community members. “Orders that were never shown,” adds the grandmother Juana.

Community members explain that a police contingent of approximately 5,000 agents, “along with groups that we know are paid for by the company (Naturaceites)”, circled the community for hours until the early morning when “they attacked us.” Prior to this, the community had already been attacked two months before on October 26, 2022.

The women in the community stood up and took control of the situation. They confronted the police contingent. “Through a megaphone, we asked what was going on, if we were drug traffickers, or if we were doing something illegal for which we were being criminalized and persecuted in this manner. Well they didn’t respond. On the contrary, they just entered the community,” explains Alba María Choc to Avispa Midia, in her Maya Q’eqchi’ language. María Choc was threatened and detained that day, together with her 14-year-old son. “They entered the community jokingly firing their rifles and pistols,” she remembers.

Ancestral authority Pedro Cuc next to his family. Photo: Aldo Santiago

Like in western films, posters were printed with three photos of the ancestral authorities offering 50,000-quetzal rewards to anyone who could provide information about the land defenders. “The state was distributing posters throughout El Estor with our photos offering compensation in exchange for information about us,” explains Pedro Cuc Pan to Avispa Midia. Pedro Cuc Pan is one of the three ancestral authorities being persecuted. He is a member of the Maya Q’eqchi’ Ancestral Council of Chapín Abajo which has declared resistance against mining and industrial oil palm plantations, also known as African palm.

At the moment, there is a tense calm in the territory. The memory of violence is still present especially among the children and elders. The possibility for a new military invasion at the moment is latent. “The arrest warrants remain active,” explains Pedro Cuc.

Chapín Abajo is cornered by African palm plantations. Photo: Aldo Santiago

The Land Belongs to Who?

In Chapín Abajo, around 200 families live on four hectares. This community is surrounded by oil palm plantations belonging to the company Naturaceites, which boasts 100% certification by RSPO standards (Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil).

Families don’t have sufficient space for their subsistence crops, nor to raise animals. Neither is there sufficient space for construction projects essential to the community like a school for the children.

The zone is controlled by company security and soldiers. “We are surveilled constantly, including by drones,” says Ana Coc.

Naturaceites argues that all of the lands where they have plantations belong to them. They also say in their reports that they have titles ensuring their ownership of the lands. However, the communities and organizations have a different perspective on how the company accumulated the lands.

The company states that it has 11,736 hectares of their own land, and another 16,249 hectares which belong to associated producers in the municipalities of Fray Bartolomé de las Casas, Alta Verapaz; San Luis, Petén; Panzós, Alta Verapaz; and El Estor, Izabal.

According to information from the company, in the Polochic valley where Chapín Abajo is located, they possess 6,000 non-continuous hectares of oil palm plantations and also a processing plant. The company’s commercial brands are Capullo, Cora, and Great Taste.

Erwin Tut, of the Guillermo Toriello Foundation, which offers counsel and accompaniment not only to Chapín Abajo but also to other communities affected by the palm oil and mining industries in the region, told Avispa Midia that gradually “the communities were being cornered in by oil palm.”

The strategy used by Naturaceites was to appropriate the lands little by little, and in many cases register the lands in their name “in an irregular way,” explains Tut. “There is extensive land grabbing going on and there are a lot of connections to the government,” he says.

The Law of the Office of Control of Land Reserves, for example, orders that lands within 200 meters of the lake’s shore belong to the state. “But what happens, the oil palms are all along the lake’s shore. If we make a complaint, the company says that it has titles to those lands. So how did they get them?” he asks.

Oil palm plantation on the shores of Lake Izabal. Photo: Aldo Santiago

Another case that illustrates the shady ways in which Naturaceites has been acquiring land is that of the Indigenous Maya Q’eqchi’ Oswaldo Rey Chub Caal. He was captured and accused of land usurpation during the eviction of the community Palestina in November of 2021, in the Chabiland Estate, in Chinebal, south of El Estor. The legal complaint was filed by the company Naturaceites who claims the lands belong to them.

He was in prison for nine months. In the end, the company couldn’t prove the accusations against him and he was freed. Caal, who is from the community of Chapín Abajo and was present that day in solidarity during the violent eviction of Palestina, was freed because the company couldn’t prove that it is the owner of the land. The land titles presented during the legal process did not correspond to the estate in El Estor, rather pertaining to another jurisdiction, to the municipality of Livingston.

Oswaldo Rey Chub Caal. Photo Renata Bessi

That begs the question: “How could Caal be accused by Naturaceites of usurping the land that they have no way of proving is theirs?”, asked the lawyer of the Indigenous Peoples Law Firm, Juan Castro, who defended the Indigenous Maya Q’eqchi’ in court.

Based on that same property title, the lawyer explains, there are a series of arrest warrants against other community members that were present during the eviction.

“We, the organizations, as well as the communities, do not have the resources to do a comprehensive study of the land occupations and the cadastral records. It is very expensive. The state doesn’t have any interest in doing it. Yet in studies that we have been able to do of specific cases, we have come across this reality, with the same anomalous logic of land appropriations,” argues the lawyer of the Indigenous Peoples Law Firm.

“We Don’t Need a Document to Say That This Land is Ours”

A lawyer for the Indigenous Peoples Law Firm, Juan Castro, explains that during the colonial period the Maya Q’eqchi’ were not people who developed land titles, as occurred in other regions of Guatemala, whose titles were conserved until the present day.

Having a title meant buying one’s own land from the Spanish crown. In consequence, it meant having to submit to a tributary regime present at the time.

Afterwards, with the creation of the land registry around 1870, “many of these lands were titled to individuals and also to public estates. However, in spite of not having titles to the lands, the communities remained,” the lawyer points out.

“These are communities who don’t have land titles, but have historically maintained possession of the lands and have a historical relationship with the territory,” Castro emphasizes.

The Plan for Municipal Development and Land Use in the municipality of El Estor 2018-2032 identifies Chapín Abajo as one of the locations with “greater antiquity and importance due to their population density and Q’echi’ belonging.” In addition to Chapín Abajo, they mention other locations in the Lake Isabel basin: Nueva Esperanza, Lancetillo, Chinebal, Río Zarquito, Pataxté, Chichipate, Setal and Selempin. “The land does not belong to us because a document says so or because an engineer says so. We belong to the land because our ancestors have died here and because we were born here. So, we defend it,” said Pedro Cuc.

Alba María, a Maya Q’eqchi’ woman who was detained alongside her 14-year-old son in the attack on the community on December 6. Photo: Renata Bessi

Community members on recuperated lands. Photo: Renata Bessi

Children Who Survived the Armed Conflict Today Reclaim the Lands of Their Ancestors

While the grandmother Juana explained to us how she felt as the bullets struck behind her feet in the attack on December 6, 2022, she reflects on other experiences of violence that happened in the same place, 40 years earlier, during Guatemala’s internal armed conflict (1960-1996).

“How is it possible that in Guatemala we are returning to the 1980’s, when they killed many children and elders. That is what we are currently seeing today. These companies don’t merely come to dispossess us of our lands, but they come to exterminate our population as Maya Q’eqchi’ people,” says the woman.

Pedro Cuc remembers that the causes of the internal armed conflict are the same causes generating people’s resistance today. “A long time ago, companies from other countries like Germany, Spain, and the United States arrived to invest in coffee, banana, cotton, and cattle. Since then, they have obtained lands by brute force, dispossessing us and taking over the lands of Indigenous peoples. It was for that reason that the insurgency began,” says Pedro Cuc.

For the Guatemalan state, which was led at that time by the military, the entire society became the enemy. Not only those involved in the armed struggle were persecuted, but so too was everyone they thought to be opposed to their interests, principally economic interests. Indigenous and campesino communities were the target of this repression. They used the internal armed conflict to justify a scorched earth policy.

The Commission for Historical Clarification (CEH) named by the United Nations to collect historical information related to the internal armed conflict estimates that 200,000 people were killed, 45,000 disappeared, and around 100,000 displaced as a consequence of the conflict. According to the CEH, government forces are responsible for 93% of the violence in the conflict, and the guerilla groups 3%.

There were massacres of entire Indigenous and campesino communities. “There are communities that were honestly exterminated and there are communities that were dispossessed of their lands because the inhabitants fled to the mountains to escape the massacres. Or they went to other countries, such as Mexico,” says Pedro Cuc.

The history of Chapín Abajo and the region of the Polochic Valley which is now part of the community was not any different. Pedro Choc, another Indigenous authority also being persecuted with a 50,000-quetzal reward, now 40 years old, lived with his father on these lands until he was 8, during the time of the internal armed conflict.

Pedro Choc, Maya Q’eqchi’ Maya ancestral authority. Photo: Renata Bessi

He had to leave his community, his father was killed. “We grew up. We were the children who managed to grow up during those times. My father was massacred by soldiers who protected the companies, just like today. They signed for peace, but I don’t know why, because there is no change. The soldiers of the past are those who today provide security for the companies. They are the police. We know who they are,” he tells the Avispa Midia team.

The Guatemalan businessman Juan Maegli Müller is the owner of Naturaceites. His family is of Swizz-German origin, arriving to Guatemala during the Liberal Reform, in the 19th century.

According to the organization Entre Mundos, in a report published in April of 2022, the family of this businessman is considered “one of the largest landowners in the region. They participated in the National Liberation Movement (MLN) political party financing paramilitaries and counterinsurgent repressive campaigns between 1970s-1980s” during the internal armed conflict. Because of the massacres and the dispossession, “the lands were left vacant for the companies and estate owners to establish their businesses,” says Pedro Cuc. “What has affected us is the oil palm plantations, and their consequences in our territory. What we have managed to recuperate thus far is this small space,” referring to the community.

The War against Mayas in the Polochic Valley

According to a report from the Commission for Historical Clarification, Guatemala Memoria del Silencio, in 1964 different communities who lived for decades on the shores of the Polochic river began organizing to reclaim land titles via the National Institute for Agrarian Transformation (INTA). This institute was created in 1962. However, the lands were given to the large landowners.

According to the report, in some cases the landowners manipulated state institutions, like the INTA, in order to neutralize land claims. The military supported the landowners against the communities’ land claims beneath the accusation that the Indigenous and campesinos were communists.

According to the study, it was the demand for land which generated the violent reaction from municipal authorities, the army, and landowners in the region. This resulted in the “Panzos Massacre” on May 29, 1978.

According to the report, after the massacre the army began a selective campaign of repression against Mayan priests and community leaders who were reclaiming their lands in the Polochic Valley where Chapín Abajo is located. The CEH registered 310 victims among the disappeared and extrajudicially executed by the soldiers, military commissioners, and civilian self-defense patrols between 1978-1982.

As a result of these events, corpses of Indigenous people were seen floating in the Polochic river on a daily basis. According to the CEH, a person who worked on a development project in the Polochic Valley between 1978-1982 declared, “Daily, on my may to work, I imagined that they were the same corpses that I saw in the river, although I knew that was not possible because the current was too strong, and each day brought new dead.”

Maya Q’eqchi’ women. Photo: Renata Bessi

The Institutions of the State?

Today there doesn’t exist a land regularization process for the communities in the region, nor a space for dialogue on the subject. What does exist is land regularization according to the interests of the company.

Tut cites one example in the community of Manguito 1, about an hour from Chapin Abajo. The estate has around 21 caballerias—a caballeria is an agricultural parcel of 6 to 43 hectares. Of these 21 caballerias, half of them are run by Naturaceites with an oil palm plantation. “What does Naturaceites say to the community? ‘Look, we didn’t come hear to fight. We can facilitate that you obtain your land title where you are located, and you just let us work where the oil palm is already planted.’ As if they were the owners of these lands,” says the Tut.

Before the creation of the Land Fund Act, the entity that regulates land in Guatemala which was created in 1999 as a product of the peace accords following the end of the internal armed conflict, there was the National Institute for Agrarian Transformation (INTA). “The INTA had accompanied various communities and they were on the verge of having their legal certification. With the arrival of oil palm, this entire process ended,” says Tut.

Now the situation is more complicated, he explains, because the government that took power on January 20, 2022, got rid of various agencies, like the Secretariat of Agrarian Affairs. This was “the entity closest to the communities in dialogue on issues related to land conflicts, as is the case of the estate of Chapín Abajo” says Tut.

The Land Fund only registers the land. The Secretariat of Agrarian Affairs had the duty of resolving conflicts “before the process of regularization arrived to the Fund,” explains Tut.

The Secretariat of Agrarian Affairs was also the government institution which had collected information about the different land conflicts throughout the country. Now, as the lawyer Castro comments, it is very difficult to get access to those documents because of the removal of the Secretariat. “They left us unarmed in the face of the landowners,” he says.

Another institution created after the signing of the peace accords was the Registry of Cadastral Information, but “the registry only declares that there exist anomalies, and does not take up the restoration of the land,” adds the legal advisor.

The new administration created the Presidential Commission for Peace. “When you ask them for mediation they say, ‘well, we don’t have the faculties to resolve agrarian conflicts,’” according to the lawyer Castro.

Indigenous Rights

Maya Q’eqchi’ children play in the community of Chapín Abajo. Photo: Renata Bessi

The figure of “Indigenous lands” doesn’t exist in the country or in the legal framework allowing the “demarcation of Indigenous lands.” When the Land Fund Act sought to regularize lands for Indigenous peoples, it was done by buying the lands. It is necessary that the landowner wants to sell the land. The state subsidizes it, but the communities have to pay a portion,” explains Castro. Currently it is very difficult for these land purchases to take place, he says.

For the lawyer Castro, civil law in Guatemala isn’t capable of understanding the historic relation that Indigenous communities have with their lands. “What civil law privileges are documents. And when a landowner who has a document says that this is mine and it is registered, that alone is sufficient for him to be considered the owner without considering that the community has existed for 200 years on these lands,” he laments.

The lawyer mentions that just over five years ago, the Constitutional Court, the maximum tribunal in constitutional material in Guatemala, issued important rulings in favor of the rights of the communities. “The court recognized that there exist other forms of property relations that are not regulated in constitutional Article 67 and that grant rights to Indigenous communities. But there was a change in the court and all those advances were rolled back. Now the only way forward is to go to the Interamerican Commission and afterwards the Interamerican Court. However, those are very long processes,” explains the lawyer, whose law firm litigates in defense of the rights of Indigenous peoples in different parts of Guatemala.

One of the few legal tools that exist in the country to defend Indigenous territories is the “protective action or writ of amparo.”

This is a mechanism to solve an urgent question in cases where human rights are being violated, like in this dispossession, “because clearly, when you are dispossessed from your land, your basic rights are being violated like the right to housing, food, education, healthcare,” says the lawyer.

In the face of institutional neglect, it’s up to the communities themselves to do the necessary research to uncover the irregularities in Naturaceites’ acquisition of the lands. “However, it is difficult to have sufficient resources to carry out studies that can sustain a legal process of land defense. It is very difficult to file an ordinary civil lawsuit. It is very expensive. It is necessary to carry out measurements, research, anthropological studies.”

The institutions, both administrative and judicial, are not sufficient to resolve an Indigenous agrarian conflict with more than 200 years of history. “Thus, it opens a pathway for the state and companies to directly use the legal route, which implies evictions and arrest warrants,” adds the lawyer.

The people assume that there is no other way but to organize to resist and survive the evictions and arrest warrants, he laments.

Oil palm advances on the forests. Photo: Aldo Santiago

Oil Palm Advances on the Nature Reserve

Naturaceitas says in its sustainability reports that its oil palm plantations are between two protected areas, the Sierra de las Minas Biosphere Reserve, which is 242,642 hectares and recognized by UNESCO, and the Bocas del Polochic Wildlife Refuge, which is 20,760 hectares, a wetland internationally recognized by the Ramsar Convention. The Ramsar Convention seeks to protect wetlands of international importance, especially as habitats for aquatic birds.

The Indigenous communities, as well as government environmental agencies and different investigations, have proven that the oil palm also advances on the environmental reserves.

The fourth “Update of the Master Plan of the Sierra de las Minas Biosphere Reserve” mentions that, according to recommendations of the National Council for Protected Areas (CONAP), African oil palm cultivation is considered one of the potential threats to the reserve. “The growth of agroindustry activity is taking place at the expense of the forested areas, in many cases without any planning other than the need for land to plant and produce raw material for industries.”

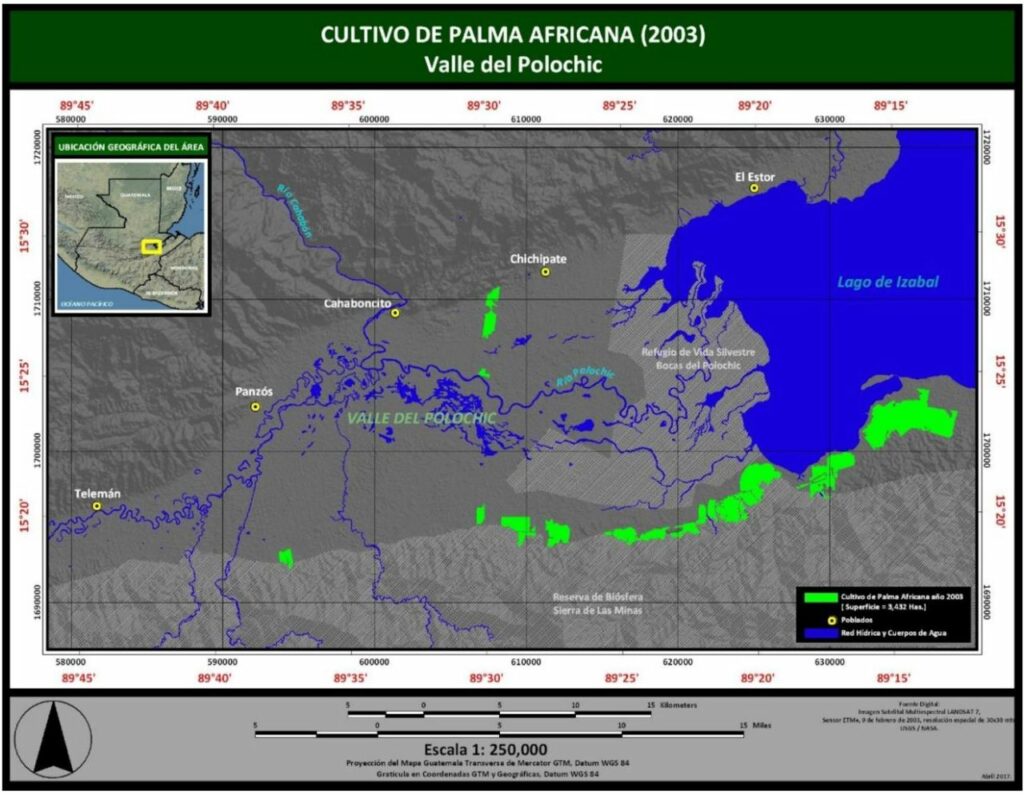

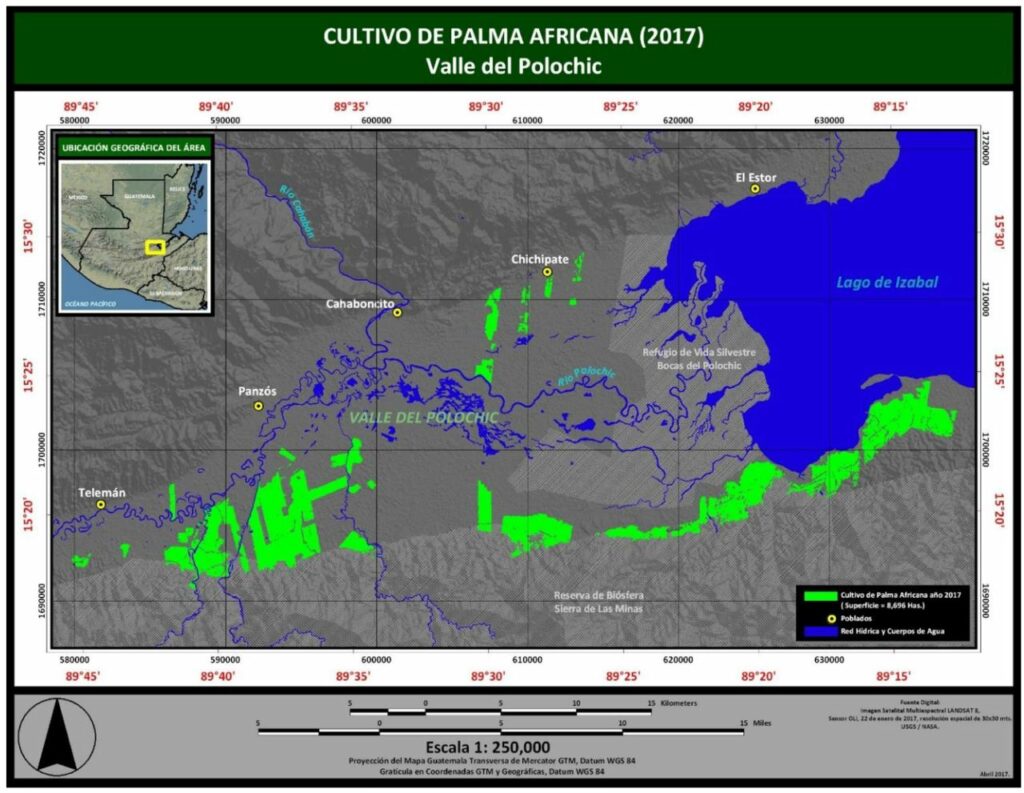

Another document, “Riesgos de la Agroindustria de la Palma Africana para las Áreas Protegidas y Diversidad Biológica en Guatemala,” of the CONAP, alerts that the expansion of African oil palm cultivation advances very quickly in protected areas. The Sierra de las Minas Biosphere Reserve is one of the areas cited by the environmental agency. A study by the biologist Heidy Amely García de la Vega entitled, “Dinámica del uso del suelo asociado al cultivo de palma africana (Elaeis guieensis Jacq,) durante el periodo 1995-2017 en el Valle del Polochic,” carried out at the University of San Carlos de Guatemala, determined that as of 2017, the area covered with African oil palm plantations in the Polochic Valley is 8,696 hectares. A total of 1,477.2 (17%) are in protected areas (1,477 in the Sierra de las Minas Biosphere Reserve and 0.2 in the Bocas del Polochic Wildlife Refuge).

Source: Investigation “Dinámica del uso del suelo asociado al cultivo de palma africana (Elaeis guineensis Jacq,) durante el periodo 1995-2017 en el valle del Polochic,” by Heidy Amely García de la Vega

The “Master Plan of the Sierra de las Minas Biosphere Reserve” establishes four types of zoning. In the core, multiple use, and recuperation zones, “the introduction of new intensive cultivation of exotic flora, both forest and non-forest species, will not be allowed.”

In the buffer zones, “the introduction of new intensive crops must be authorized by the Executive Secretary of the National Council for Protected Areas, based on scientific criteria which demonstrates that they do not interfere in the ecological processes for which the areas were created.”

“The oil palm, as an exotic plant, needs environmental impact studies. Not one plantation of oil palm in Guatemala has those studies,” signaled the lawyer of the Law Firm for Indigenous Peoples.

Naturaceites argues that since 2015 it has had a policy of “zero deforestation,” the same period in which its RSPO certification was approved.

To “compensate” for the damage it has caused, the company reports that it will contribute for 25 years to the financing of the Perú-Peruito project. This project covers a forest area of 9,400 hectares to the south of the Laguna del Tigre National Park, part of the Maya Biosphere Reserve. There, the national organization Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) and the National Council for Protected Areas (CONAP) are both participating.

African oil palm has advanced toward the limits of the Sierra de las Minas Biosphere Reserve. Photo: Aldo Santiago

Double Expulsion

In the flatter southern part of Lake Izabal, at the foot of the Sierra de las Minas mountains, the lands were taken by the palm oil company Naturaceites, leaving the more mountainous region available for possible occupation by the communities. However, there aren’t any areas to live because they were declared property of the Sierra de las Minas Biosphere Reserve in 1990, the same year that it fell under the control and management of the Environmental Defenders Foundation (FDN).

FDN’s connivance with the oil palm plantations does not apply when it comes to the subsistence needs of the communities. “When they attempt to enter into the reserve they are evicted. They cannot return to their lands because they have been taken over by oil palm. Nor can they go to live in the mountains because they are protected by organizations that do not allow the presence of people. So, there is nowhere for the people to go,” says Castro.

If someone wants to plant corn or beans, “they have to put their seeds in a high-risk zone, in areas that are vulnerable for the crop, while the major landowners are established in the most fertile areas,” says the Indigenous Pedro Cuc.

In addition, they are controlled areas, “there is a lot of surveillance, almost nobody can enter,” says Erwin Tut. In 2020, for example, “the Guaritas community, isolated by oil palm, tried to recuperate lands that belonged to them inside the reserve. Environmental Defenders asked for their eviction and they were removed,” comments Tut.

Naturaceites and the Environmental Defenders Foundation possess agreements in different conservation projects. One of them is the program of diversity identification and monitoring in the Sierra de las Minas and Lake Izabal.

Six areas were identified as high conservation value (HCV) with “a biological, ecological, social, or cultural value exceptionally significant or of critical importance,” according to the reports. All of them are in public areas, in the reserves.

Based on the study, “we have defined and implemented five protection programs of HCV areas.” The “protection” of areas considered of high conservation value is one of the necessary points to achieve and maintain RSPO certification.

The RSPO team responded to questions sent by Avispa Midia via email in March of this year where they explained the importance of the HCV areas for certification: “The RSPO certification requires assessments of high conservation value and the High Carbon Stock Approach to identify, protect, and conserve the forest and other areas of importance for biodiversity, water resources, and the ecosystems….”.

In other words, the business uses forests on public lands to maintain their certification, which is necessary to have access to European and North American markets, while making it difficult for communities to have access to these same forests.

Environmental Defenders?

On their website, the Environmental Defenders Foundation is very touching in explaining the origins of their organization: “After meeting, Thor Janson and Magaly Rey Rosa discovered a mutual love for the natural world eventually leading them to unite forces in 1983 and work together to defend the environment and bring a “green” philosophy to Guatemalan society.”

One of the people who helped “do the groundwork for the foundation” was Luis Movil, general manager of Esso/Exxon of Central America during that time “who provided the necessary funding to produce the first official documents” of the organization.

Today their allies are: United States Agency for International Development (USAID), US Fish and Wildlife Service, Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), the European Union, and the conservation organizations Rainforest Alliance, World Wildlife Fund (WWF), and the Nature Conservancy.

In a 2021 document, the USAID, who are active in the region with different conservation projects, emphasized how “important it has been to establish allies for the development of conservation strategies of the reserve with national and international organizations and the private sector, which even facilitated that the Environmental Defenders Foundation acquired properties in the core zone.”

Maya Q’eqchi women planting corn on the recuperated ancestral lands. Photo: Renata Bessi

Responsibility to Past and Future Generations

The monotonous views of oil palms which seem to extend infinitely can be seen behind the community. There, trunks of palm trees are being replaced by the planting of corn, rice, beans, bananas, and a diversity of fruits. The children play, climbing up and down the trunks, that are at least 25 years old.

Here, just over a year ago, the community members of Chapín Abajo began the recuperation of lands despite threats from the two military detachments that surveil them at all times.

Strong community organization is needed to cut down the oil palm. “Well-organized, we can cut down 400 oil palms per day,” say the community members while they accompany the Avispa team on a tour of the occupied lands.

“When I was born here, it was a large community. Today it has been greatly reduced by the conflict. Many went to live in the mountains. At that time, they were called guerrillas, but they weren’t guerrillas, they were campesinos, farmers. The company invaded all of these lands. That is why we are upset, we are returning to recuperate them again,” says Pedro Choc.

Having land and planting it is not only a right, it is a responsibility, explains Mariano Choc Bol, whose parents were also assassinated on these lands during the internal armed conflict. “We have to stand up and take back what was taken from our ancestors. We have this responsibility to our parents and our children.”

The Maya Q’eqchi’ of Chapín Abajo explain that the process of land recuperation continues. “It is difficult work, but not impossible,” says Pedro Cuc. The objective, according to him, is to achieve food sovereignty and autonomy as a community. “The idea that we have as an organization is to be independent, never ask them for work. To access the land whether they agree or not. We are going to recuperate these lands at whatever cost. If one day we have to pay the price with our lives, there are youth, children, women, and young parents who are in the struggle. They will continue fighting until we get what belongs to us as people. This struggle will not be abandoned as long as there is life,” says Pedro Cuc.

Recuperated lands in the community of Chapín Abajo. Photos: Renata Bessi, Aldo Santiago, and Santiago Navarro F