In the memory of the people, knowledge of plants, water, and mountains, of how to be a community and what it means to serve the community, is safeguarded and maintained. Generation after generation, in a ritualistic way, this knowledge is passed down through spoken word. In the heart of the Sierra mountains of the Mexican state of Puebla, Masewal and Tutunaku peoples decided to expand and preserve the power of the spoken word through an Indigenous radio, Radio Tosepan Limakxtum.

In 2010, the founders of the radio were debating the best way not of starting the radio, but of defending it. “We discussed how seeking a concession meant accepting the programmatic guidelines of the Federal Electoral Institute (IFE). Not having a concession meant running the risk of being classified as a clandestine or pirate radio,” explains Bonifacio Iturbide Palomo, a collaborator of the radio.

The decision had to be made by the maximum authority in the community, the assembly. There it was decided to support the initiative. Through collective work (known as faena) and economic donations, without permission from the state, they built the radio cabin and bought the necessary equipment. They also received training. “It was not until September 2011 that we launched our first broadcast. Our main topics were how to care for mother earth, the importance of our Indigenous language, traditional medicine, and identity. We focused on community harmony and its importance for us as Indigenous peoples,” explains a collaborator of Radio Tosepan to Avispa Midia.

In 2013, the Mexican government implemented a telecommunications and radio broadcasting reform which ordered the legal recognition of community and Indigenous radios through concessions. As of today, there are 140 community radios with concessions, 18 of them registered as Indigenous radios, according to data from the United Nations.

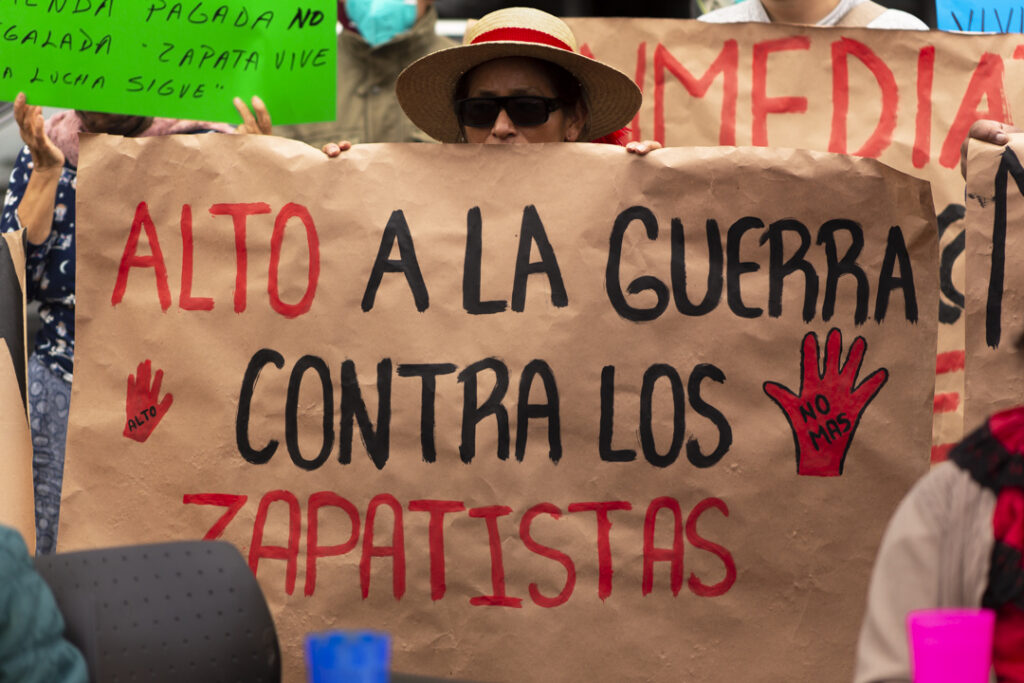

The reform didn’t come out of nowhere, but rather derived from the necessity to concretize what had been stipulated in the San Andrés Accords; agreements reached in dialogues between the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) and the Federal Government. Among other things, these accords influenced Fraction VI of Article 2 in the Mexican Constitution:

“Extend the communication infrastructure, enabling integration of communities to the rest of the country, but constructing and expanding transportation routes and telecommunication means. Also, authorities are obliged to develop the conditions required so that indigenous peoples and communities may acquire, operate and manage media, in accordance with the law.”

However, this law imposed certain restrictions and obligations on Indigenous radios, like the broadcasting of political party spots and propaganda of the National Electoral Institute (INE). “We are opposed to broadcasting these messages because they are contrary to our forms of organizing and making decisions. Our system is made up of different community positions, and is not a system of groups like political parties that divide us,” adds Iturbide.

Erick Huerta, an advisor to Radio Tosepan and lawyer for the Network of Diversity, Equity, and Sustainability, AC, explains that the main objective of Indigenous media is to strengthen the autonomy, culture, and identity of Indigenous peoples. “It is contrary to those objectives that Indigenous peoples are forced to broadcast political party advertisements. Imagine the EZLN, negotiating the San Andrés Accords, accepting the possibility to have their own radios, but having to broadcast political party propaganda,” the lawyer suggests.

“This imposition affects the autonomy of Indigenous peoples. Furthermore, it is contrary to the form in which authority is exercised in the communities. It is not organized around different groups or factions, but rather is based in mutual aid, work, and service to the community,” Huerta tells Avispa Midia.

Iturbide, a collaborator of Radio Tosepan, explains that in Masewal territory in the Sierra mountains of the state of Puebla, they have prohibited political party interference, “but recently we are seeing that their influence is present.” More and more we are seeing groups of people who want to control positions in the community, and that is not how things work. Here we have our own system, and it is not for personal interests, but for the entire community. If we permit this, the community fabric will begin to unravel,” he says.

The Legal Battle

Radio Tosepan is currently registered as an Indigenous radio and has appealed on several occasions to the Federal Electoral Tribunal in Mexico City to revoke the legal ruling made on February 27, which says “that this Indigenous radio is obligated to include in their programming political party spots.”

“So far we have not broadcasted any of these messages,” says Iturbide.

On July 5, with two votes in favor of the radio and four against it in the Electoral Tribunal, the request was denied to the community. According to the court, “No right is violated by broadcasting political party propaganda…it does not violate the customs and traditions or the internal normative systems.” The Magistrate Mónica Aralí Soto Fregoso added, “On the contrary, it is the people’s right to information.”

These communities have not let down their guard. “Before taking the case to international courts, we want to exhaust all resources in the country,” said the lawyer Huerta.

For this reason, on October 11, the president of the Auxiliary Council of the Nahua community of San Bernardino Tlaxcalancingo, Rogelio Xinto Coyol, as an Indigenous authority, filed a lawsuit to protect the collective political-electoral rights in his community, against the different acts of the INE. The lawsuit was directed specifically at the General Agreement INEC/CG445/2023, which modifies the telecommunications law and reaffirms the order to broadcast electoral propaganda.

The radios in Tlaxcalancingo and Tosepan are the only 2 radios considered for “social Indigenous use” in this region. There are 2 other community radios, 6 social radios, 12 public use radios, and 50 commercial concessions.

They point out that with at least 70 radio concessions in the state, “it is disproportionate and incomparable to consider that not broadcasting the political party messages (spots) is violating the right to information and to be informed, when the radio spectrum is 97% saturated with these messages.”

In the lawsuit, the community argues that the law “violates our collective rights to strengthen, promote, protect, and make known our own form of organization and our normative systems, as a Nahua community that has managed their own media.”

In addition, the community considers the law to be “discriminatory and racist.” Therefore, they are adhering to their self-determination and autonomy as Indigenous people, making the decision not to broadcast the propaganda. This case was again assigned to Magistrate Soto Fregoso.

In a communique released by Radio Tosepan, Radio Cholollan, and the Network of Diversity, Equity, and Sustainability, they say that the Nahua community has the authority “because the acts notoriously violate the right to autonomy of the community and their right to have their own media. Furthermore, these legal decisions were made without consultations that were previous, free, informed, and culturally adequate to Indigenous communities.”

On October 18, through the auxiliary president of the locality of Yohualichan in the municipality of Cuetzalan del Progreso, Puebla, another lawsuit was filed on behalf of the citizenry arguing that the Masewal community has the right to manage their own media according to the logic of autonomy.

“We are not going to broadcast propaganda of any political party, we are going to resort to other legal resources. Because we are defending our autonomy as organized communities,” adds Iturbide.

The lawyer Huerta assures that, if this legal battle is won, it will benefit all Indigenous and community radios in the country. “The instruction would be to the INE, annulling this obligation or broadcasting political party messages. In the meantime, these radios resort to civil disobedience because their defense is legitimate. They are not broadcasting any type of electoral publicity,” he concludes.