Translated by: Sam Warren, Photos: Santiago Navarro F., Anthony Guerra

Her name is Zara Mercedes Días Velászques; she is walking with other women accompanied by their children. She walks with a stick in her hand, which she grasps strongly, as if holding on to hope; she screws up her face and lets loose a shout. “We demand justice, police get out! Earn a living working with sweat on your brow like us! Businessmen out too, leave this place alone!” Mercedes, like the other members of her village, has been labeled a terrorist for opposing one of the most important projects in this region, a hydroelectric project, which–though it was supposed to help develop these communities–has only brought misfortune.

Zara Mercedes is from the village of Bella Linda. They are Chuj Maya peoples from the municipality of San Mateo Ixtatán, in northern Guatemala’s Department of Huehuetenango. In these lands, and in the name of “sustainable development”, three hydroelectric dams known as Pojom I, Pojom II and San Andrés have been planned that will be fed by the diversion of the Negro, Pojom, Yalwitz, Primavera, Varsovia and Palmira rivers. In response, the indigenous communities of the region have sustained a resistance effort to these projects for more than four years.

During Avispa Midia’s July 2018 visit to the Yich K’isis (or Ixquisis) micro-region of San Mateo Ixtatán, the team confirmed the presence of Guatemala’s National Civil Police (PNC, for Policía Nacional Civil) at various strategic points of the business known as PDH S.A. (for Promoción y Desarrollo Hídrico, Sociedad Anónima, or Hydrological Promotion and Development Corporation), the business in charge of the construction of the hydroelectric complex.

A military detail has been installed since May 2014, as well as private security guards, according to the national Human Rights Director of Guatemala, Miguel Colop Hernández. “The National Civil Police, around 300 units, and a detail of the Armed Forces of Guatemala can be found inside the buildings of PDH S.A.; there is also private security and this has provoked discontent among the communities. The security forces have said they just receive orders from their superiors. Though this doesn’t say anything good about the Guatemalan government”, the functionary told Avispa Midia, as he carried out his duties as observer of the peaceful demonstrations of July 2018.

There is precedent for the labeling of these communities as terrorists. In August 2017 the demonstrators launched a peaceful protest in the Yich K’isis region, where the main buildings of PDH S.A. are located. There they delivered a document to the chief military officer and to the managing official of the PNC, demanding they withdraw. More than 2,000 protesters had gathered with instructions to maintain a peaceful protest.

But moments later “some people who had their faces covered burned the machinery. We thought they were the workers themselves, but they wanted to put the blame on us”, stated Lucas Jorge García, the second-level regional president of the Yich K’isis Micro-region of San Mateo Ixtatán, to the Avispa Midia team.

Minutes later, the company gave a distorted version of the story to the media, labeling the actions as terrorist acts. The Coordinating Committee of Agricultural, Commercial, Industrial and Financial Associations (CACIF, for Comité Coordinador de Asociaciones Agrícolas, Comerciales, Industriales y Financieras) also officially described the actions as terrorist acts in an August 31 statement: “We forcefully condemn the disruptions in Ixquisis, Huehuetenango, which can only be considered terrorist acts.”

This was also true for the Association of Generators with Renewable Energy (or AGER, for Asociación de Generadores con Energía Renovable). “We repudiate the terrorist acts that are being carried out in the village of Ixquisis, municipality of San Mateo Ixtatán, Huehuetenango, committed by criminals”, they stated in an official communication also dated August 31.

The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IAHCR) warned in its December 2017 report that this language stigmatizing the protesters has been spread throughout social networks and communication media, in an attempt to delegitimize the demands of these communities. For example, civil society organizations indicated that defenders of human rights are called “professional troublemakers,” “bandits,” “professional thugs,” “failed fratricidal rabble,” “left-wing NGOs formerly terrorist organizations.”

“We’re peaceful here, we never commit violence. But they’ve blamed us for being terrorists and guerrillas. Even Monsignor Álvaro Mazzani of the Diocese of Huehuetenango has said that we’re terrorists, but this monsignor is on the side of the corporations, because he carries the blood of the Spanish who came here more than 500 years ago and that’s why he keeps fucking us over,”

SAYS LUCAS JORGE.

Antiterrorism Law

As these events were ongoing, in November 2017, the Union of National Change (UCN, for Unión del Cambio Nacional) representative Napoleón Rojas introduced an antiterrorism bill that was backed by the Congressional Governance Commission. This bill, titled "Law Against Terrorist Acts" (Ley Contra Actos Terroristas), no. 5239, composed of 58 articles, was established in accordance with the recommendations given by the Financial Action Group of Latin America (GAFI-LAT, for Grupo de Acción Financiera de Latinoamérica), the same recommendation given for the rest of the Latin American countries.

The current law, in its Chapter I, establishes that the law "is of public order and aims to regulate criminal figures related to terrorism in all its forms and manifestations; as well as to prevent, and encourage the investigation and punishment of acts of terrorist character, so as to guarantee the constitutional order, the Rule of Law."

Zara Mercedes is tired of all the intimidation, but she is determined to fight to the end. "We are fighting because we don't want to put our children at risk".

"But now there are people who step in our path and threaten us, they say we're guerrillas, terrorists. We aren't guerrillas, we are fighters, we don't carry arms, we come as we are, we come to protest. The police are the ones causing the chaos, they insult the communities and use gas against us, they're the terrorists."

Zapatistas

In January 2017 more than 2,000 protesters tried to mount a sit-in near the buildings of the hydroelectric company. But around the estate located between the community road in Pojom and the border with Mexico, a group of masked people placed wire nets from the business’s encampment and began to burn the machinery. This was documented by Prensa Comunitaria, which was present at the time. “From the forested area we began to hear the crack of rifle shots… the journalist Santiago Botón recognized the sound of the shots: they weren’t rifles that security guards could have had, but rather they were using military rifles,” denounced the witnessing journalists.

Exactly 10 minutes from the military detachment, armed men began to shoot, causing the death of a 72-year-old man, Sebastián Alonso Juan. The police and the military did not intervene to support the protesters.

Prensa Comunitaria obtained the report on the matter authored by the PNC detachment operating from inside PDH S.A., which was sent to their PNC superiors in Huehuetenango. The report claims that “at 22 hours on January 14, 2017, a group of armed Zapatistas (from the Zapatista Army of National Liberation), coming from Mexico, entered the village of Ixquisis of the municipaity of San Mateo Ixtatán, with the aim of burning uninhabited houses and taking over a cattle ranch.” The report claims that in their rounds they found a banner which stated the following: “The National Civil Police, National Army and people of PDH have 24 hours to evacuate.”

The presence of the Zapatista Army in this region was never proven; to the contrary, on June 5, 2017, World Environment Day, the IACHR indicated their concern over the murder of Sebastián Alonso Juan, for which reason–in their Press Release No. 072/17–they announced that during their visit to the village of Ixquisis, representatives from the IACHR met with the relatives of Sebastián Alonso, who stated that after he had been shot down, employees of the hydroelectric business had proceeded to hit him on one side of his face and neck while he lay dying.

The December 2017 IACHR report titled “Situation of Human Rights in Guatemala,” documented on the delegation’s visit to Ixquisis and Santa Eulalia, Department of Huehuetenango, remarks on the severe conflict generated by the various hydroelectric projects and states that at least 278 human rights defenders had been subjected to judicial proceedings and capture.“This is frequently used against communities that occupy lands targeted for the development of megaprojects and exploitation of natural resources. In the northern region alone, 500 custody warrants were in force,” states the report.

Southern Command

If this weren’t enough, on February 13 and 15, 2018, elements of Joint Task Force Bravo of the United States Southern Command (SOUTHCOM), based in Soto Cano Air Base in Comayagua, Honduras, mobilized to the municipality of Nentón, in Huehuetenango, on the Guatemalan border with Mexico. 66 members of JTF Bravo participated, including doctors and soldiers, together with the 5th Infantry Brigade of the Army of Guatemala. The soldiers were also supported by the Ministry of Public Health and Social Assistance of Guatemala, the Ministry of Defense, and the Department of Social Works of the Wife of the President of Guatemala (SOSEP, for Secretaría de Obras Sociales de la Esposa del Presidente de Guatemala), led by Guatemala’s First Lady, Patricia de Morales.

Local media documented that as part of the mobilization in Nentón, three military helicopters flew over the municipalities of San Juan Ixcoy, Santa Eulalia, San Mateo Ixtatán and Barillas.

They were seen to leave from the departmental capitol of Huehuetenango, with no known route. People from the communities noticed the helicopters because of their large size. They flew over San Mateo Ixtatán, arriving some minutes later at Yich K’isis, and then descended onto the runway located on the premises of PDH S.A.

The motive for the Southern Command’s presence in the region remains unknown. To this day, the government of Guatemala has not stated anything on the matter.

Private security

On the other hand, the private security that guards the property of the business is from a group known as Serseco, according to a statement from the spokespeople of the ministry of governance of Guatemala in January 2017, in a dialogue between the Convergence Party and the ministers of energy and mines.

The Serseco Group (for Servicios de Seguridad Consolidados, or Consolidated Security Services) was founded in 1986 and is considered a leader in comprehensive security solutions, offering services for businesses, homes, personal security guards, and many other products. They maintain a presence in various Latin American countries, including Venezuela, Panama, Colombia, Costa Rica and Ecuador, and they also have allied businesses in Spain.

“As part of its business strategy, Serseco Group has crossed borders and conquered other markets with the goal of replicating its know-how and experience in other countries. This is the case for Serseco International, which arose in 2006 and operates from the United States so as to better attend to international demand for security products”, states its official homepage.

“The business’s private security has been provoking us constantly. We are going to continue with our fight until this business leaves our communities. It doesn’t matter if they call us terrorists, because this will affect us, this will affect our children. It’s for them that we fight”, adds Zara Mercedes.

Sustainable development

A campesino (small-scale farmer) of no more than 60 years of age, who did not wish to give his name for safety reasons, shows the Río Negro to the Avispa Midia team, takes a few sips of water and washes his face to show the water is clean. He says that when the company arrived, "right when they got here they said they were going to build a small plant, to give public lighting and energy to the 31 communities who don't have it, and they said they were going to do it for climate change. Then they started to divert the river."

According to the investors in this hydroelectric complex, managed by PDH S.A., the project is projected to avoid the production of greenhouse gases equivalent to that generated by nearly 25,000 cars every year. The investors maintain that this is more than enough for the project to be considered "sustainable development" for the region. As such, in addition to the benefits acquired through the sale of power, the investors will receive compensation through Certified Emission Reductions (CERs). Each CER is equivalent to a ton of carbon dioxide (tCO2), usually sold on the stock market as Carbon Bonds to those countries or industries who seek to offset their emission limits or to pay for the right to emit more greenhouse gases with these certificates.

The people of the communities object to this sustainable development. "We don't agree with the development, we want them to leave our territory alone. We don't believe in this development that kills, that violates and that makes use of the police and the army. They also destroy our communities. Here we have respect for our holy Earth", says the second-level regional president of the Microregion of Ixquisis.

Maril Hernández Martínez, a young woman of 17 years of age, says that PDH S.A. has threatened them with death for living close to their buildings. "We don't know where those people come from. We're of the water, and we live from her. We don't need the corporations; we know how to live here just as we are. We want to live lives full of peace and joy. Before we were calm and happy, but when the company arrived, it sowed hatred. The company's workers come to intimidate us, threaten to kill us with their weapons," the young woman tells Avispa Midia.

Name change

October 3, 2017, PDH S.A. announced publicly that the business was closing a cycle, and so would evolve into a new business model. “Now we are Energy and Renewal (Energía y Renovación), and we’re betting on sustainable development,” they announced in their statement.

Lucas Jorge looks skeptical when we ask him about the name change, and without hesitation claims that “the company changed its name because of the number of complaints it was receiving, for the violation of human rights in the communities resisting peacefully”, and because “the PNC and the business’s private security shot at us. They killed Sebastián Alonso Juan from the Yulchen Frontera community”, says the president of Ixquisis.

This context of violence stands in sharp contrast to the position of Energy and Renewal, which boasts on its official homepage of its respect for “the diversity and cultural richness of the area,” and also promises to promote environmental sustainability, openness to dialogue and consensus, stating that they are “respectful of human rights and believe in accountability.”

The referendum

For the dissenters, the dialogue was broken ever since the business and the Guatemalan government refused to recognize the results of their referendum that was carried on in 2009, together with the then-mayor of San Mateo Ixtatán, Andrés Alonso Pascual. The Community Referendum was publicized in the 66 villages [inglés no distingue entre “aldea” y “caserío,” así que sumé los números] that make up the municipality. 25,646 people participated, 99% of whom rejected the presence of extractive, mining and hydroelectric projects.

The business and the government of Guatemala have tried to negotiate several times with the residents of the communities, and have attempted to win them over with highways, schools, medical centers and even the promise of a new referendum, but the townspeople are resolved not to accept any project in their communities. “As young people we ask for the withdrawal of the company known as PDH, as there is no longer anything to discuss. We don’t want anything from them. We don’t want to be left without water, and so we demand that the government withdraw the police, withdraw this company. Because they are draining their wastewaters into the water we drink. They have offered us drinking water, but we don’t need it, because we drink from the river and we live from the river, but they’re polluting it”, denounces Maril Hernández.

Water

The pollution of these rivers goes against the needs of these communities. According to figures gathered by the IACHR, nearly 3 million people in Guatemala lack access to drinkable water and approximately 6 million don't have access to improved sanitation services. Among the population living in extreme poverty, 40% don't have access to improved sources of water. Guatemala is the only Central American country with no law governing bodies of water. Additionally, in rural areas there are grave problems with access to drinkable water because of drought, diversion of rivers and monopolization of water by the business sector.

In this region, where water flows everywhere, the hydroelectric stations in total aim to generate 170,000 additional megawatt hours of renewable energy annually, which will travel to the market through the Interconnection Networks for the Regional Central American Market (MRC, for Mercado Regional Centroamericano). "So far, efforts to advance regional electrical integration have centered on the design and execution of the project 'Central American Electrical Interconnection System" (SIEPAC, for Sistema de Interconexión Eléctrica de los Países de América Central), the construction of the first regional transmission system and the implementation of a competitive energy market with the participation of every Central American country", announced the Inter-American Development Bank in its 2017 report on Central American electrical integration.

Interconnection

The corporation known as PDH S.A., now "Energy and Renewal", was officially registered in 2007 with its legal representative, Carlos Eduardo Rodas Marzano.

Marzano served as Presidential Commissioner of the Government of Guatemala, holding the post of Advisor of the Ministry of Foreign Relations with Rank of Special Envoy for the Puebla-Panama Plan (PPP), now known as the Mesoamerica Project. This integration project was presented in 2000 by the then-president of Mexico, Vicente Fox Quezada; since then the agenda and cash flow has predominantly come from the United States.

The project aims to expand the free market from southern Mexico to the rest of Central America, where the various governments promised to initiate the so-called "Mesoamerican Initiatives", in eight components: sustainable development, human development, disaster prevention and mitigation, tourism promotion, facilitation of commercial trade, road integration, electrical interconnection, and telecommunications integration.

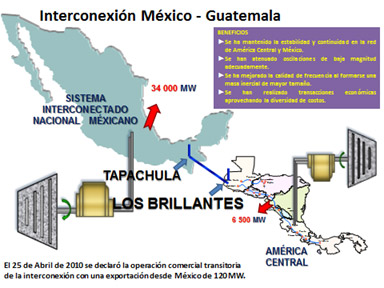

In 2001, within the framework of the PPP and in order to promote Central American integration, the Inter-American Development Bank announced the Guatemala-Mexico electrical interconnection project, which complemented "the SIEPAC, a $320 million project to develop the first regional transmission network of the Central American power grid and a wholesale electricity market," stated the IDB, proclaiming its promise--along with Spanish businesses--to support the project.

Mexico, as permanent president of the Mesoamerica Project, has utilized the Mexican Agency of International Cooperation for Development (AMEXCID, for Agencia Mexicana de Cooperación Internacional para el Desarrollo) to promote the creation of SIEPAC, with an extension of 1120 miles (1800 km) and a network of 40,400 miles (65000 km) of fiberoptic cable. A network that goes from Guatemala to Panama and extends to Colombia, an infrastructure where the Regional Electrical market began operations in 2014. Mexican investors have contributed 11% of the total amount invested by SIEPAC's proprietary company; U.S., Spanish, Central American and Colombian businesses have also invested in the project.

According to the 2016 Statistical Report of the Directorate General of Guatemala, that year 58% of the country's energy consumption was met with renewable resources. 440.6 megawatts of energy production were installed in total, of which 60% were hydroelectric plants and 40% were geothermal plants. In total approximately 2,444 more kilowatts were installed in 2016, of which the business known as DEORSA represented 57%, followed by EEGSA with 37% and DEOCSA with 6%. [esta parte no me quedó muy claro; dice 440.6 mW instalados en 2016, y luego 2,444 kilowatts] The three businesses are based on international capital from the Spanish business known as Gas Natural Fenosa.

In May 2011 the British investment fund Actis acquired the stocks of Deorsa and Deocsa for a sum of $345 million USD paid to Gas Natural Fenosa and renamed the two businesses Energuate. In 2016 the company IC Power Ltd, from the investment fund I Squared Capital (ISQ), and a subsidiary of Kenon Holding Israel, an Israeli company that operates power grids in Peru, Colombia, Chile, parts of the Caribbean, Israel, and now Guatemala, acquired Energuate.

In the same Statistical Report it was announced that since 2016 "Guatemala exports electricity to the Regional Electric Market (MER) and Mexico," and that in that year alone around 11% of the national production was exported. "98% of the exports were to the MER and the first offers of energy exportation to Mexico by Guatemalan agents were observed."

"We know this energy isn't for the communities, it's for the transnationals. They're installing some pretty thick cables. Many say it's going to Mexico. We don't matter to the transnationals,"

SHARES MARIL HERNÁNDEZ.

One of the points where energy flows from Guatemala to Mexico is through the 50-mile (80 km), 400 kilovolt electric line that connects the Mexican substation in Tapachula and the Guatemalan substation in Los Brillantes, and which began operations in 2010. Through May 2018, the sales to Mexico had reached some $7.2 million USD, while energy exports to Central America generated $44.2 million USD, according to figures from the Bank of Guatemala (Banguat).

The Inter-American Development Bank has promoted SIEPAC as an engine of growth and competition in Central America. In the April 2018 meeting in its headquarters, with representation from the US State Department as well as the Mexican government, MER authorities, and delegations from Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Panama, the bank reaffirmed its commitment. "The IDB is committed to remaining the strategic partner for the region and to supporting its energy integration process. To that end, the Bank supports and provides technical cooperation and other financial resources."

The meeting also highlighted the commitment to continuing the electrical interconnection project between Guatemala and Mexico with the consolidation of Mexican interconnection and SIEPAC. "A study for the overall design of the integration of the Mexican electricity market with SIEPAC will be concluded this year; work will continue on a feasibility study expected to be ready in the first half of 2019."

"All we have left is to fight. If we don't fight now, tomorrow we won't have our land. We won't have water and there won't be corn. We'll die of hunger. The company and the government must understand this: their development is our death", concludes Maril, the young woman of 17 years.