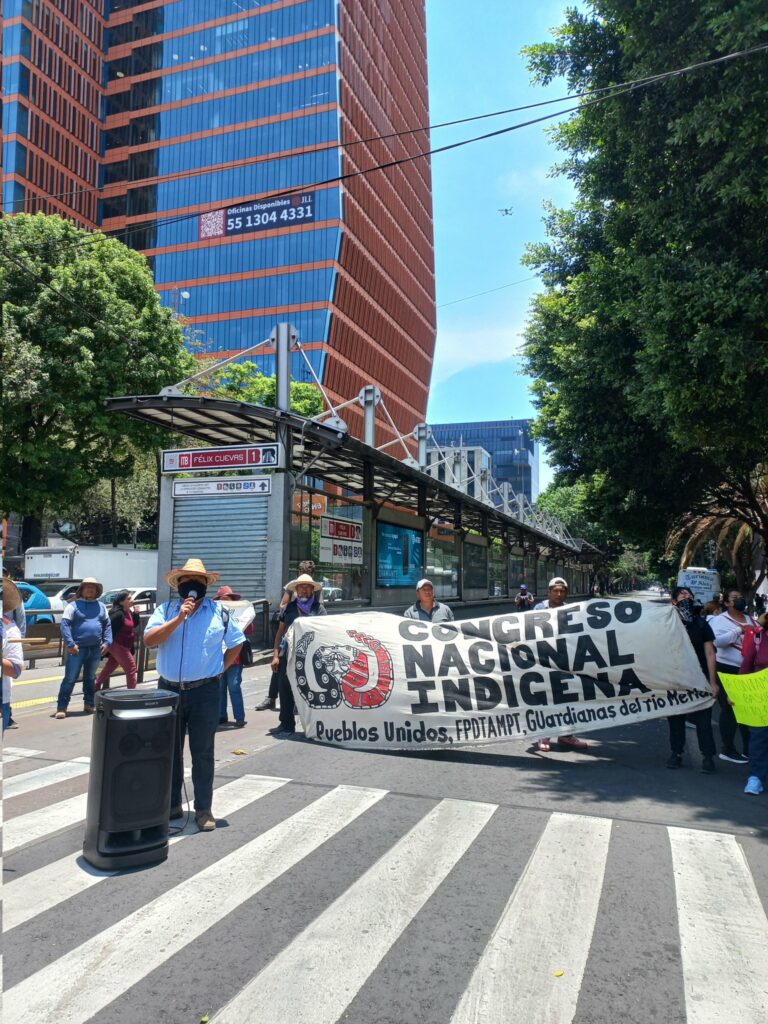

Cover image: Members of the Supreme Indigenous Council of Michoacán mobilize to demand the freedom of María Cruz Paz, who has been detained for two weeks on what they say are fabricated charges.

On Monday, June 17, hundreds of Indigenous Purépechas, members of the Supreme Indigenous Council of Michoacán (CSIM), blockaded highways in different parts of the state to demand the freedom of María Cruz Paz Zamora, who they say is a political prisoner.

Paz Zamora, delegate of the National Indigenous Congress (CNI), was detained on June 5 by ministerial police of Michoacán, and taken to prison in Uruapan.

Members of the Supreme Indigenous Council of Michoacán mobilize to demand the freedom of María Cruz Paz, who has been detained for two weeks on what they say are fabricated charges.

The CSIM—made up of civil, communal, and traditional authorities of 70 Purépecha, Nahua, Otomí, and Mazahua communities—says that the Michoacán State Public Prosecutor’s Office has held her in custody for the crime of forced disappearance. The Indigenous organization says that she is a victim of criminalization due to her work as a defender of the environment, territory, and Indigenous autonomy.

According to the Indigenous council, Paz Zamora wasn’t offered any explanation for her detention, which occurred while she was traveling to the city of Morelia to attend a meeting with state officials.

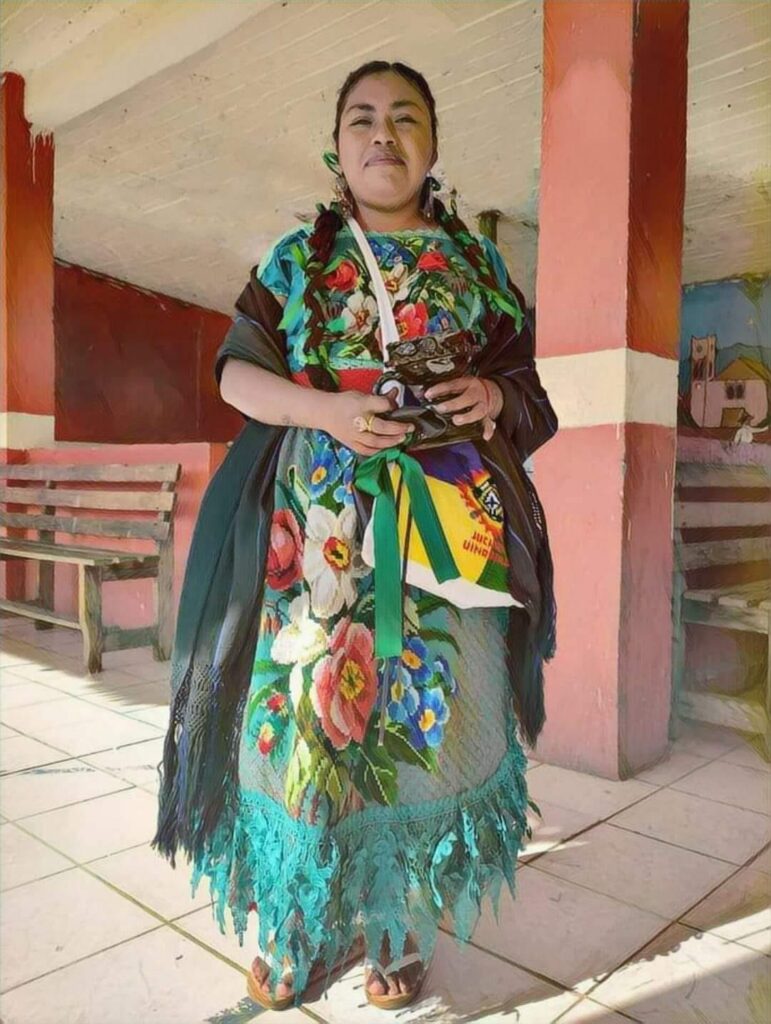

María Cruz Paz Zamora, resident of the Purépecha community of Ocumicho.

Paz Zamora is a member of the community of Ocumicho, in the municipality of Cherapan, where she is recognized for her work in defense of Purépecha culture, and for the autonomy of the community. Furthermore, the Supreme Indigenous Council of Michoacan points out that she was working on extensive reforestation projects in her community, which has brought her face to face with illegal loggers and agro-industrial avocado producers in the region.

The National indigenous Congress (CNI) explains that the Mexican State and the Michoacán State Public Prosecutor’s Office repress and criminalize those who oppose the irritational depredation of the forests and the sale of ancestral lands. They too demand the immediate freedom of Paz Zamora.

Antecedents of Violence

According to the CSIM spokesperson, Pavel Guzmán Ulianov, the imprisonment of the Purépecha organizer can only be understood by reviewing the history and context of the Indigenous community of Ocumicho—a community that has defended their ancestral territory, and which, during the last 40 years, has suffered a series of aggressions.

During a press conference carried out in the capital city of Morelia, Ulianov listed several violent acts committed against the Indigenous community, including the assassination of the communal lands secretary, Prudencio Ortíz Alonso, on May 31, 2020, during an attack where the communal lands representative was also injured.

Also noteworthy is the disappearance of the coordinator of the communal governance council and the director of Radio Indígena Ocumicho, Esteban Cruz Rosas, on April 28, 2022, as he was leaving the radio station. According to the CSIM, thanks to the timely mobilization, Cruz was found alive.

In addition, he explained that on November 11, 2022, the community was attacked by an armed group, and on December 10 of that same year, Pedro Pascual Cruz was assassinated, who was the coordinator of the communal guard of Ocumicho.

“All these cases have been denounced in time and form in the Michoacan Public Prosecutor’s Office. However, in this institution the paradox of impunity prevails, the guilty go free and the innocent are imprisoned,” explained the spokesperson.

Paz Zamora’s mother, who was also present in the demand for the release of her daughter, says that she is accused on fabricated evidence.

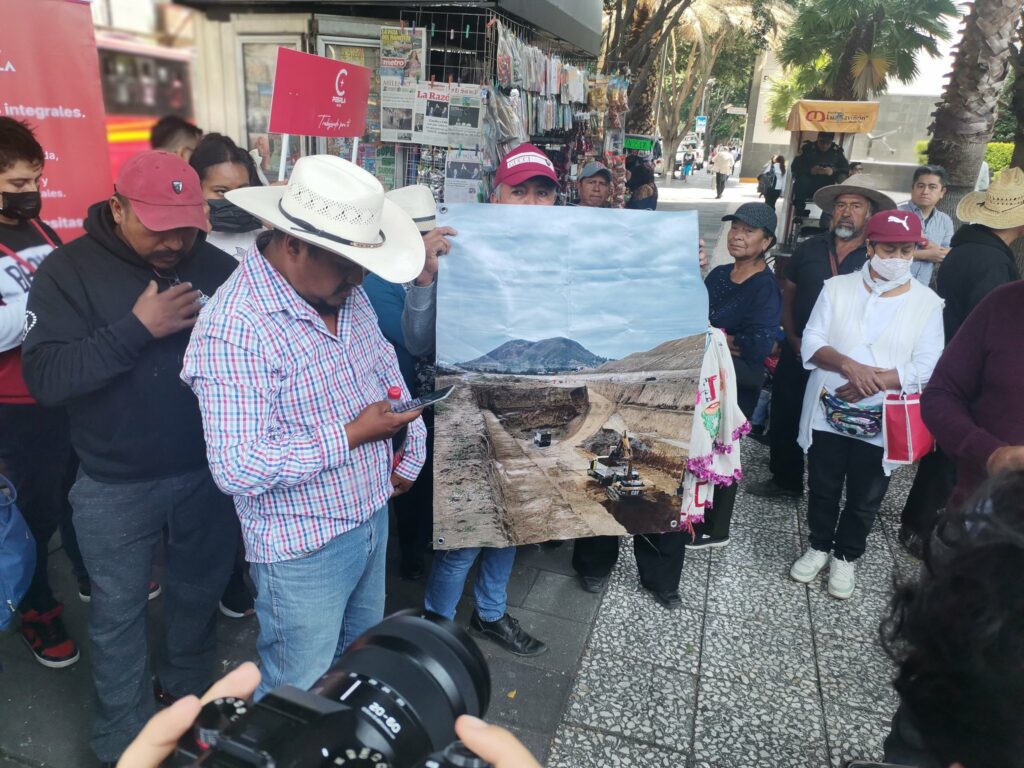

Press conference carried out in Morelia to demand the immediate freedom of María Cruz Paz Zamora.

Cruz Rosas, who also participated in the press conference, says that the aggressions against Ocumicho have occurred in spite of having officially asked for assistance from state and federal authorities. “We are marginalized, we have never been attended to,” accused the coordinator.

Cruz says that the detention of Paz Zamora is the consequence of the fabrication of crimes on part of the Michoacán Public Prosecutor’s Office, to “find a scapegoat” to blame in the case of the disappearance of two community members of Santa Cruz Tanaco, Israel Vargas Jerónimo and Oscar Vargas Campos, which occurred on January 3, 2024.

The coordinator of the communal government of Ocumicho assures that Paz Zamora remains imprisoned for the accusation from a protected witness, of which, says the coordinator, is an illegal logger who accuses the forest defender of being behind the kidnapping of the community members.

“How is a criminal going to have more voice and vote than a person that has been in charge of 20 men who guard the forest?”, Cruz emphatically asked in front of the media. “Maybe that is why she is being attacked, because here in Michoacán, there is nobody to defend the forests,” he said.