Foto de portada: Renata Bessi

The Chortí Mayan community of Azacualpa, in the state of Copán, northeastern Honduras, sits on a hill that is part of a huge gold vein mined by Minerales de Occidente S.A de C.V. (Minosa), a subsidiary of the Canadian mining company Aura Minerals.

Minosa began the on the lower part of the hill, near Azacualpa. “Every day at the foot of the hill they blow up dynamite,” Yesica Rodríguez, a resident of the community, told Avispa Midia. “The sound is incredible.”

The strip mine is expanding daily towards the top of the hill, destroying everything in its path. Now, the mining company is targeting the community’s traditional cemetery, which contains some 338 million ounces of gold, according to a report by the Center for Democracy Studies.

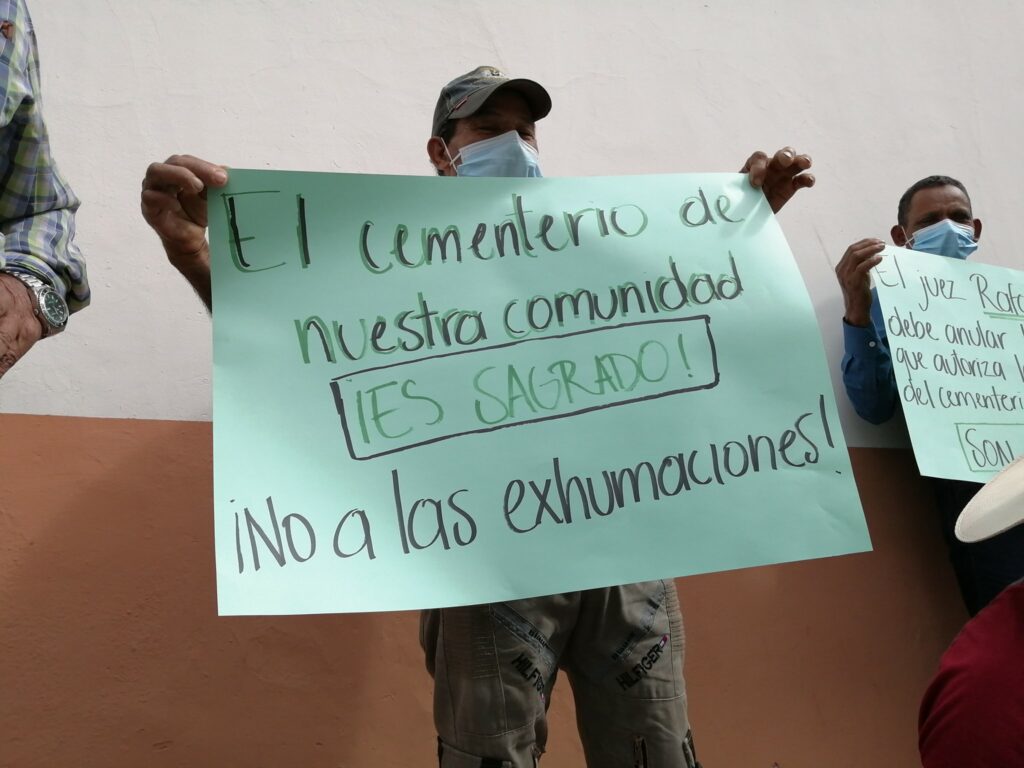

Minosa has spared no effort to dig up the remains of the community’s ancestors. Immediately in response to residents’ resistance and protest, police occupied the cemetery and surrounding area to guard the company’s equipment while it removed the bodies.

On February 20th, Minosa employees came at dawn, protected by the armed forces and the National Police. It was later, when the soldiers and officials had left, that the family members who opposed the exhumations were allowed to enter and “obviously our souls ached seeing the disaster they had left. The ground was dug up everywhere,” said Rodríguez, who is part of the Committee of Those Affected by Minosa.

The company reported that it had exhumed all bodies from the cemetery. “According to them, they took out all the corpses, but we’re certain that it wasn’t all of them, only the ones in mausoleums. They wrecked the cemetery, dug up graves, all to make it look like they’d exhumed all the bodies. We believe that there are still remains of our relatives churned up in the land the excavated,” said Rodríguez.

Furthermore, she said, the community was not told where their families’ remains were taken. The new cemetery is on the same hill—however, according to Rodríguez, the graves are unmarked. “No one knows which bodies are which, we don’t know where they are, we can’t go visit them, and what’s more, the new cemetery will be moved again because it’s in the mining zone.”

What happens now, she said, is that the company will “clean the terrain,” to remove the earth already excavated in order to use dynamite. On February 22nd, Minosa “went so far as to enter the cemetery at four in the morning to begin removing the land.”

The conflict has been evident to the community since 2012, when the company’s plans to remove Azacualpa cemetery were made public. “It is unjust for outsiders to come in and destroy our territory, our culture, the land where our ancestors rest,” said Rodríguez.

Generations of Destruction

Just above the cemetery sits the community of Azacualpa, part of the area allotted to Minosa. “Destroying the part below will leave us hanging over a chasm. It’s logical that they want to destroy our village as well (...) but we won’t let them.”

Azacualpa wouldn’t be the first community in the area to disappear. The villages of San Andrés, Platanares, and San Miguel were relocated in the 1990s. In San Andrés, a church with colonial artifacts from the 18th century—which was even designated a cultural and historical heritage site—was abandoned in the mining area.

Land that had been full of life, animals, water, and pine forests is now dry, orange, covered in dust, and guarded by Minosa security. Huge craters and leach pads dot the slopes of the hill, along with an immense amount of machinery. The sound of the wind in the pine leaves has been replaced by the noise of bulldozers and dump trucks carrying tons of brush.

In 2016, when the battle over the cemetery was reaching its peak, the Avispa Midia team was in Azacualpa to document.

María Rodríguez Villanueva, now 52 years old, was a child when communities were being relocated. She said that her parents, along with many other families, came to live in Azacualpa because “there was nowhere left to build houses on the land the company had assigned them, Nueva San Andrés.” Furthermore, the company did not pay what it had promised for the houses’ construction.

When they uprooted San Andrés, her sister was president of the community trust. She remembers that some of the community were in agreement with the move, but not others. “Those who did not want to leave resisted. The last ones left faced off against company bulldozers that came to destroy the whole village. I remember one young man who didn’t want to leave—they fractured his spine with their machine. In the end they removed him because he was injured. He recovered and went to the United States.”

When Minosa first arrived in the 1980s, her father warned of the risks. “My dad said: ‘there’s a company coming and they’re going to be destructive, they’ll destroy the land and what’s on it.’ But we never thought it would go this far. If we’d realized at the time, we never would have let it begin.”

“I also remember that we would pass through here carrying firewood,” she said, pointing at the company’s operational area, where everything is arid. “Everything was forested, beautiful—there was even water here.”

Unlike Villanueva, Yesica Rodríguez isn’t lucky enough to remember an Azacualpa without the mining company. Rodríguez is 21. “I grew up in this battle with Minosa.” She recalls witnessing the conflict since she was a child. “I remember that people would hold demonstrations and the police would come, throw tear gas, beat people.”

She remembers, too, that children were told in school that the community could not exist without the mine. “There was one instructor who taught us that the company was everything to our survival. Now I see clearly that that’s not the case, it doesn’t help us, it destroys us, violates our rights, and humiliates us. If our ancestors could live off the land, I believe we can too,” said Rodriguez.

Cemetery in the courts

In 2015, the community of Azacualpa determined through an open town hall meeting that the cemetery is a cultural heritage site and therefore neither the exhumations nor the graveyard’s destruction would be permitted. “Despite this, the mining company, together with the municipality of La Unión and the Ministry of Health, began exhumation processes in the cemetery,” the Studies for Dignity Law Firm, which provides legal advice to the community, explained in a statement.

Legal remedies were pursued. The Supreme Court of Justice (CSJ) issued an injunction that protected the cemetery from destruction and mandated its repair.

Defying the Supreme Court’s decision, an October 2021 resolution by judge Rafael Rivera Tábora of the Court of Santa Rosa de Copán ordered the exhumation, transfer, and reburial of human remains from the Chortí Maya cemetery to be carried out “urgently.”

In November 2021, a nullification hearing was held against Judge Rivera’s ruling. “Despite ample demonstration that his authorization violated the CSJ’s decision, which ordered the protection of the cemetery, the judge declared the nullification request, the objective of which was the preservation and protection of the community cemetery, to be without merit,” the Studies for Dignity Law Firm explained on social media.

So, they forcibly exhumed remains against the wishes of family members of the deceased.

In his resolution, the judge also ignored the community’s Chortí Mayan identity and the cemetery’s heritage and historical value for the residents of Azacualpa.

Taking into account both the judicial proceedings and the contempt for the order of protection by the CSJ, the Studies for Dignity Law Firm filed a complaint of judicial malfeasance against Judge Rafael Rivera Tábora before the Special Prosecutor for Transparency and the Fight Against Public Corruption.

According to statements made by the firm's lawyers in local media, none of the local judicial authorities recognized the Chortí Mayan identity of Azacualpa’s residents, although the identity was recognized initially by the CSJ in its order of protection.

Green Mining

During Avispa Midia’s visit to Azacualpa, we interviewed José Armando Acosta Contreras, who worked for Minosa for some 20 years. Contreras was fired after being accused of acting against the company by defending his community cemetery, and later his blood was found to be contaminated with heavy metals such as arsenic, mercury, and lead, leading to ongoing health problems.

Despite evidence to the contrary, Minosa maintains that its business is “focused on sustainable development.” For Contreras, there is no such thing as an environmentally responsible mining company. “Sustainable development,” for those who understand mining from the inside, is a joke. “Otherwise they wouldn't harm the forests, or kill the animals. There used to be many animals in these hills, birds of all kinds, squirrels, deer, even coyotes. Also, the five springs we used to have no longer exist. Little by little, the company has destroyed all of this,” he told Avispa Midia.

There is no shortage of complaints of pollution. According to a report by the Center for Democracy Studies, there were cyanide and heavy metal spills in the Lara River in 2003, 2009, and 2017. “Several other studies have shown that the discharge of wastewater by the mining company into the waters of the Lara River presents a serious danger in the short and medium term to the health of local residents” and those in the surrounding municipalities, the report confirms.

The Azacualpa Environmental Committee stated that it believes there has been even more discharge than acknowledge, and that Minosa personnel clean up and collect the evidence. The situation is worrisome as no one controls the discharge and its effects, nor does the company face penalties.