Leaders of the Tohono O’odham Nation, an Indigenous tribe divided by the US-Mexico border, denounced this week the destruction of their sacred sites to make way for the construction of a new section of the border wall between the states of Arizona and Sonora.

On Wednesday, February 26, tribal leaders from both sides of the border protested at the base of Monument Hill, an ancient burial site where the O’odham used to lay to rest the remains of the Apache warriors they killed in battle. The tribe’s studies also indicate that their ancestors used the site for religious ceremonies.

Not far from the protest, a group of journalists invited by the United States Customs and Border Patrol (CBP) watched a controlled detonation of explosives. A military explosives expert with the US Army Corps of Engineers told reporters that the blastwould prepare the site for the construction a 30 foot steel wall, part of President Donald Trump’s controversial plan to renovate and expand 175 miles of the border barrier.

“To state it clearly, we are enduring crimes against humanity,” said Verlon M. José, the governor of the Tohono O’odham in Mexico. “Tell me where your grandparents are buried and let me dynamite their graves”.

Meanwhile, in Washington D.C., the chair of the Tohono O’odham Nation in the United States, Ned Norris Jr., testified at a congressional hearing entitled, “destroying sacred sites and erasing tribal culture”. “I know in my heart and what our elders have told us and what we have learned—that that area is home to our ancestors”.

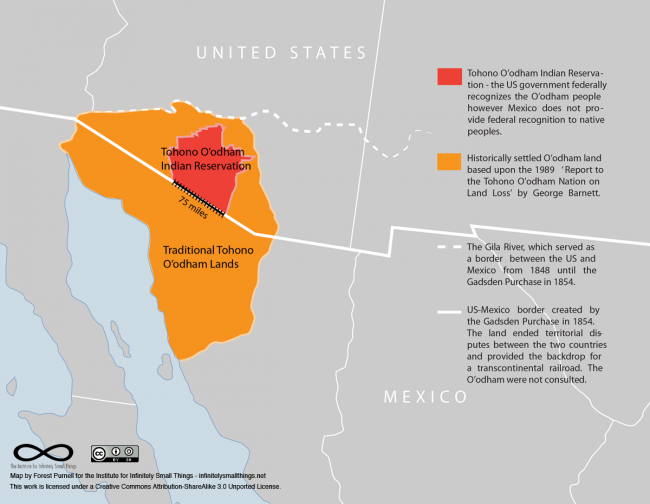

Until the 1970s, the Tohono O’odham—called Papagos by Spanish colonizers—crossed freely over the border between the Unites States and Mexico. But in recent decades the O’odham have watched as an increasingly militarized border has split their homeland definitively in two. Today, some 28,000 members of the tribe live on the Tohono O’odham Reservation in Arizona. Another 2,000 live in the northern Mexican state of Sonora, where the Mexican government doesn’t recognize their land rights.

In addition to being part of the O’odham’s historic heritage Monument Hill is located partially within the Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, an international biosphere reserve established to protect dozens of endemic plants and animals, including several endangered species.

“It’s heartbreaking to watch them butcher this spectacular national monument and desecrate sacred indigenous lands”, said Laiken Jordahl, an activist with the Center for Biological Diversity, an organization that works to protect endangered species. Since 2017, the Center has been suing the Trump administration for environmental and constitutional violations related to the expansion of the border barrier. And since last year, Jordahl has documented the destruction of saguaro and organ pipe cactuses to make way for the reinforced wall, which Trump is rushing to finish before competing in November’s presidential elections.

Jordahl emphasized that some of the saguaros—a protected species that can live up to 200 years—“have been here longer than the border itself. What right do we think we have to destroy something like that?”

In a press release, the Center for Biological Diversity said that to mix concrete for the bollard fence construction crews are pumping water from an aquifer that nourishes a rare desert oasis. According to the Border Patrol’s own data they are extracting an average of 84,000 gallons of water a day from the aquifer that feeds the Quitobaquito Spring.

The pumping jeopardizes not only the spring but also two endangered species that depend on it for survival: the Sonoyta mud turtle and the Quitobaquito pupfish. The spring has also enabled the survival of the O’odham people for thousands of years. In 2019, construction crews working near the spring found what are believed to be human remainsthat date to the classic Hohokam period, between 300 and 1500 A.D.

The Border Patrol disputed the claims of Indigenous and environmental advocates. In a statement, Border Patrol spokesman John Mennell insisted that “no biological, cultural or historical sites were identified within the project area”. In addition, he said that the work teams had relocated hundreds of cactuses within the park, and were only destroying those “determined not to be in a healthy enough state to be relocated”.

Both the cactuses and the O’odham sacred sites are normally protected by U.S. law. However, the Trump administration has waived dozens of regulations to expedite the construction of the border fence, including those protecting Indigenous territories and endangered species. In 2018, the U.S. Supreme Court refused to hear a lawsuit challenging the administration’s authority to waive these laws.

And so construction is progressing on a section of the wall that is destined to run along the entire southern edge of the Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument. Scientists have no doubt that the barrier will limit the geographic range of critically endangered species. However, its impact on human migration is less certain. In the 2019 fiscal year CBP only reported making 14,265 apprehensions in the Tucson sector, where the National Monument is located, compared to 205,000 apprehensions in the Rio Grande Valley of Texas.

In an opinion column, Rick Smith, a retired Regional Director of the U.S. National Park Service, questioned the logic of a new border fence. “If the effectiveness of the existing barrier and its impacts have not been disclosed to the public, how do we know that a new border wall is necessary?,” he asked. “What we do know is that a wall will threaten the delicate balance of a critical ecosystem. So is building a wall that may not be successful worth impacting national parks and harming threatened and endangered wildlife? It is not.”