Campesino observes the lands where the construction of a solar farm is being proposed.

By Renata Bessi

Alberto Hernández Toledo is an 82-year-old Indigenous Zapotec from the community of San Pedro Comitancillo, located in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, Oaxaca, in southern Mexico. He is a campesino who learned from his parents how to care for and work the land, the same as his children, who today are teachers.

Some months ago, the campesino Hernández Toledo received a visit to his home from unknown people offering “wonderful things, wealth, and easy money,” as he describes. They were looking for the Indigenous Zapotec because he is an ejido member of the community and he has lands that he inherited from his parents and grandparents.

The people who visited him identified themselves as representatives of the company, Helax Istmo, a subsidiary of the Danish company, Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners (CIP).

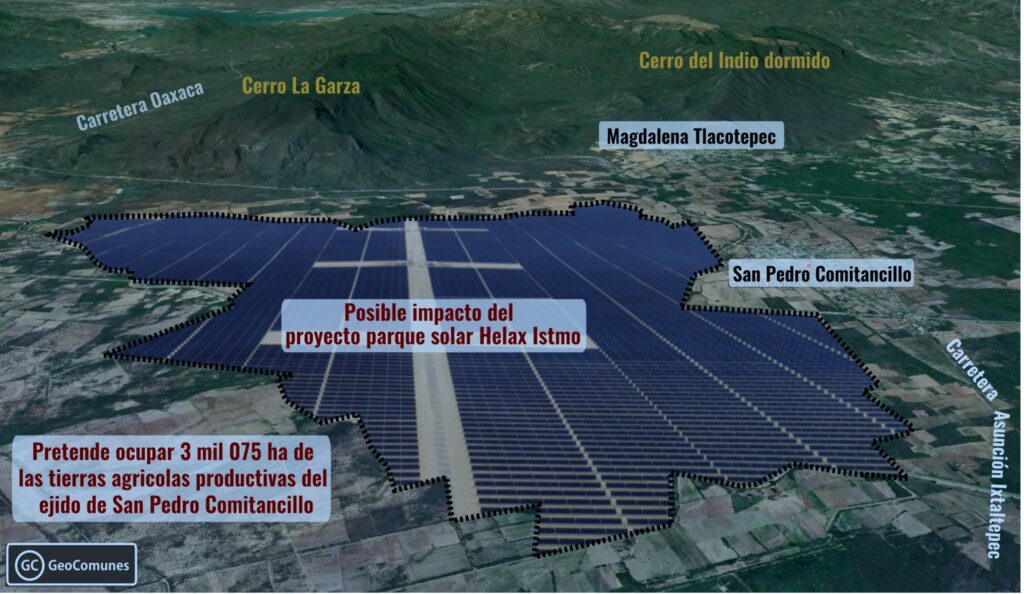

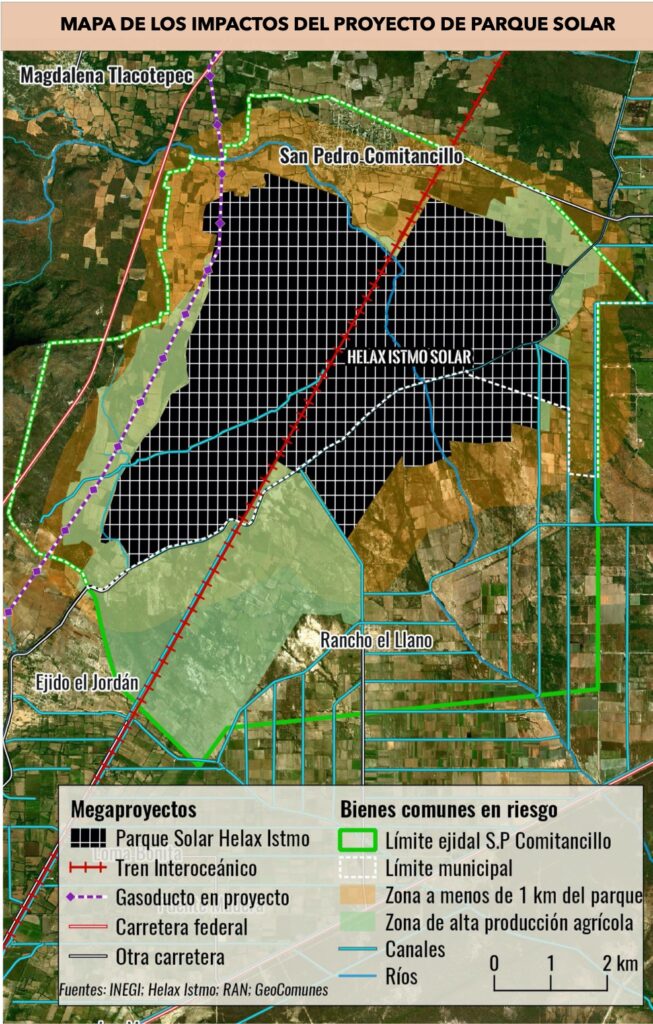

They proposed to the campesino that he lease his ejido lands for the production of what they consider to be “green energy.” The Danish company plans to construct a solar farm, the largest in Mexico, in an area covering 3,070 hectares of Comitancillo, 40% of the territory of the community, equivalent to more than 750 times the size of the central plaza of Mexico City. As if that were not enough, it will be installed only 400 meters from the urban center of the community. “They tried, but they didn’t convince me,” says the Zapotec.

The project’s polygon coincides with the grand majority of the fertile lands of the community. “It is there where we plant organic sesame that we export,” comments Luis Vázquez,” another ejido member that the company sought out to individually convince him to rent his lands. “These lands are really flat, and that is what they need for the installation of the solar panels,” he said.

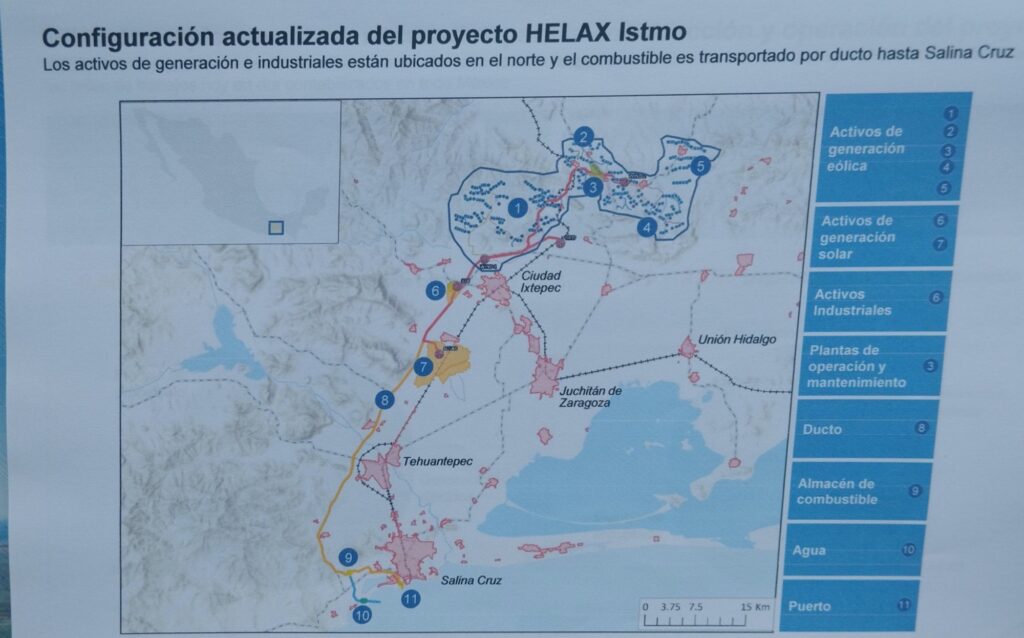

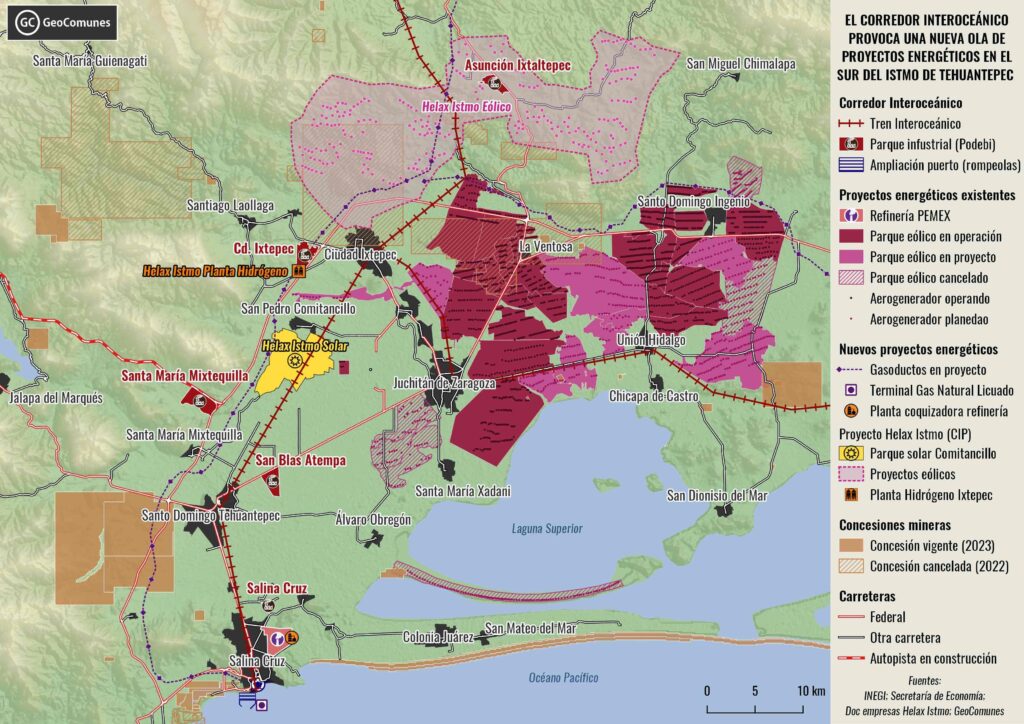

The solar farm is not an isolated project. It is part of a complex of energy production and infrastructure—wind farms, gas and water pipelines, fuel storage facilities, and terminals in the port of Salina Cruz—all run by Helax Istmo.

The objective of the complex is to produce what has been considered the fuel of the future, green energy, in the region of the Interoceanic Corridor of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, in the section where Comitancillo is located.

Helax Istmo plans to construct a large green hydrogen plant in one of the ten “development parks” planned along the industrial corridor of the Isthmus, specifically in the community near Comitancillo, Ixtepec.

The idea is that the energy produced by the solar farm in Comitancillo—as well as the energy from five new wind parks on the lands of Ixtepec and Ixtaltepec—will power the green hydrogen production plant in Ixtepec, which needs excessive amounts of energy and water.

The Danish company, in presence of the President of Mexico, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, on December 22, 2023, signed a memorandum of understanding with the Mexican Navy and the Interoceanic Corridor of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec—a public agency of the federal government created in 2019 to carry out the “project for the development of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec”—to install the plant. The green hydrogen is planned to serve to generate “green maritime fuel.”

In a communique, the company said that the project will contribute “to the objective of sustainable development in Mexico, as well as the decarbonization of shipping on the world scale,” projected for the thousands of vessels that arrive to the ports of Salina Cruz and Coatzacoalcos, which the Interoceanic Corridor connects together.

Philip Cristiani, a partner of Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners, details that “when it is fully operational, Helax will be in an ideal position to attend to the growing demand of ecological fuel for shipping, contributing in a significant way to the decarbonization of the global shipping industry.”

“When they came to my house, they tried to tell me about the nice things that the solar farm would bring to us. But how are we to imagine nice things in a territory of more than 3,000 hectares taken over by solar panels that are like a giant mirror that reflects the sun’s rays? The heat is no longer like it used to be. We cannot live with so much heat. We are going to be even more unprotected, without trees, and without land to plant. I don’t agree,” insists the campesino Hernández Toledo.

How is “green hydrogen” produced?

The electric energy derived from the solar farm and the wind parks will power the process of electrolysis which takes place at the hydrogen plant, using electrical current to separate the hydrogen from the oxygen in water. That is to say, the molecule H2O (water) is divided into O2 (oxygen) and H2 (hydrogen). It is called “green hydrogen” because the electricity used in the process is obtained from “renewable sources” and, with the hydrogen obtained from these sources, energy can be produced without emitting carbon dioxide that contaminates the atmosphere as occurs with fossil fuels.

Immoral and Illegal

Helax Istmo has increased its presence in the territory of Comitancillo since the end of 2023, trying to talk with and convince local authorities, ejido members, and leaders of the community.

According to neighbors and ejido members interviewed for this article, the company is politically manipulating the issue by promoting the solar farm as a project pushed by the president of the republic.

“They are taking advantage of the popularity or the acceptance of AMLO in the communities. So, at first, they proposed it as a project of the government, to afterwards say that it is a private project,” Guillermo Hernández Antonio explains, son of an ejido member, teacher, and farmer of sesame, squash, and corn on the lands that coincide with the polygon of the project.

Community representatives explain that in spite of the signing of the memorandum of understanding between the federal government and the company for the construction of the hydrogen plant, as of the publication of this report, in the ejido commission of Comitancillo, not one document has been signed with the company for the construction of the solar farm. The company has yet to receive approval from Comitancillo’s ejido assembly, the maximum authority.

At the Secretariat of Energy (SENER), according to the solicitude for information (folio # 330026124000211), with a response from April 8, 2024, there is no environmental impact report that approves the project, something required for any company to develop an energy project.

Members of GeoComunes warn that as long as this permit hasn’t been approved, according to Article 86 of the Electric Industry Law, “the company doesn’t have authorization to begin to negotiate with owners of the land. If they go ahead with the project, they would be committing a crime,” they point out.

According to the regulation, those interested in obtaining permission or authorization to develop projects in the electricity industry, including those related to the provision of the workforce of Electric Power Generation, Transmission, and Distribution, must present to the Secretariat of Energy, the social impact report referring to article 120 of the law, 90 days before their intention to start the negotiations with the property owners where the project in question is intended to be located.

For Hernández Antonio, the home visits are also immoral. “They do not have the authorization to carry them out.” They say that “they are carrying out a survey of information to gauge support for the project, but in the end it is meant to convince individual ejido members, to prepare the terrain for a possible governmental consultation,” sustains Hernández Antonio, who is also the coordinator of the Autonomous Communal University of Oaxaca (UACO) in Comitancillo.

In the same request for access to information, the location, technical, and methodological information of the projects—hydrogen plant, wind parks, and the solar farm—was requested, as well as information presented by the company to the governing body. All of these requests were denied. Among the arguments presented by SENER is that “the disclosure of information damages the commercial advantages that the companies have over their competitors…” In addition, the information is classified so as to be reserved for a period of two years.

Prior Information?

Representatives of Helax Istmo also attended an ejido assembly at the end of January 2024, to give general information about the project. “They told us of the benefits of the solar farm,” says the ejido member Luis Vázquez. On this same occasion, representatives of the company proposed an Indigenous consultation for the entire population.

The ejido assembly arrived to the conclusion that it was not the moment to make such a decision, deciding to analyze the possibility of a consultation in a reunion where representatives of the company were not present.

The reunion took place in mid-February. According to the ejido member Luis Vázquez, an extraordinary assembly was held that dealt exclusively with the approval of the consultation. “After hours of debate and under pressure from other ejido members, without a deeper analysis of the project and its impacts,” the consultation was approved with 32 votes in favor and 14 against.

Of these 32, more than a third are ejido members that “never come to the assembles and who suddenly appeared; so, we realized that they have been brought in by the Helax company,” says Hernández Antonio to the Avispa team.

In the National Agrarian Registry, 503 ejido members are recognized in Comitancillo, with approximately 110 who have passed away. At least 50% plus one of the ejido members must approve the consultation. “We weren’t even 50% of the ejido members in the assembly. There were very few of us ejido members present,” comments Luis Vázquez.

For Hernández Antonio, from the moment in which the company began the individual visits with ejido members, the consultation ceased to be free, previous, informed, and culturally appropriate, as is planted in international law.

“There is a lot of misinformation of what the project will really mean in our territory. And those who have some information, it’s information that has been distorted by the company. We demand that the government informs, but that it informs properly, that they give complete and honest information about the project. We are sure that they will not do that,” he sustained. “Thus, we’ve begun a process of informing the population ourselves about what a project like this might mean for the community,” explains Hernández Antonio.

According to an informative document presented by Helax Istmo to local authorities, to which Avispa Midia has access, the process of consultation planted by the company will take place in May. The document also states that, before the consultation, between the months of January and February, collective pre-agreements on access to the land will be carried out. “What is happening is that they are in a hurry with the elections coming up (June 2024). They want to guarantee the project before the change of government,” adds Luis Vázquez.

Regardless, “we know that they are obligated to carry out the consultation and they are going to do it. We have seen in other places how these consultations are carried out in the interests of the companies; but independent of the results, if the assembly of ejido members doesn’t give permission to construct the project, they are not going to do it,” sustains the ejido member Luis Vázquez.

There is No Water, But There is Money

Representatives of Helax Istmo told the ejido member Luis Vázquez that, although water is scarce, with the project they will have money, signifying that the ejido member will no longer depend on planting his lands.

The proposal presented to the ejido members, which consists of an informative document to local authorities, shows that the project is planned in three phases. The first phase is of development, where they will clear and prepare the land for four years. During this time, they will pay $540 pesos per hectare per year. With the observation that “the payments during this phase will be subject to the fact that ejido members must carry out the regularization and registration of their parcels of land,” says the document.

In the following phases of construction and operation, which will last 33 years, they propose $23,000 pesos per hectare per year.

“What do you do with money? The paper isn’t going to save us from the unbearable heat, or the lack of water and food,” says community member Elia Cruz Cruz. “Here there is less and less water and we’ve already been alerted to the fact that, with the solar farms like this one, the water will decrease even more.”

Furthermore, “we who are not ejido members also have to be taken into consideration,” she claims. “I went to the ejido assembly when they approved the consultation to say to them that they have to consider us and think about the community as a whole because the impacts will affect everyone,” the housewife explains.

Elia, a 71-year-old campesina, isn’t an ejido member, but owns land where she planted crops with her husband. After her husband died, she has farmed the land by herself. Everyday at 6:30 in the morning, she’s already working the land. On her lands she maintains around 2,750 fruit and timber trees, acquired through the Sembrando Vida program.

She also plants corn, beans, squash, and sesame. She has 854 nopal plants which are an important weekly income. “For the crops, I carry water around 180 meters from the water source to the land. Sometimes with a gas pump, but when it isn’t working, I have to carry the water in a wheelbarrow,” she explains. “It is a lot of work. Why don’t they carry out a smaller project that helps us maintain the lands green, to recuperate the water?”

Elvia points out that information hasn’t been provided about the real impacts of the project, and water is one of the things that she is most worried about. “If there isn’t water for the ejido members, then much less for us, the neighbors and small landholders. How could they want to do a consultation that supposedly will be in May if the majority of the community isn’t even aware of it? They can’t sell the life of the community. We are going to be alert to what is on the horizon,” says the campesina.

Desert

“Nothing survives around the solar panels, not even grass. The animals flee,” says Julio Ramírez Ortiz of the municipality of Calpulalpan in the state of Tlaxcala, where a solar farm project was implemented in 2019 by the French company Engie.

The experience of Ramírez Ortiz, also an ejido member, was shared in an informative forum which took place in Comitancillo, explaining what happened in his community. “We let the company enter our community, and we didn’t know of the impacts.” For this reason, they decided to organize in the October 16 Collective, meant to defend the territory of the community after the arrival of the company.

In Calpulalpan there were nearly 5,000 solar panels installed on 600 hectares. In Comitancillo, the space planned for the project is four times greater, 3,000 hectares of land, just 400 meters from the urban center.

“The surface of solar megaprojects in Mexico vary between 200 and 1,500 hectares. The largest that exists in Mexico is 2,400 hectares, in Villanueva (Coahuila). The community closest to the park is 10km away,” highlights members of GeoComunes.

Solar park in Villanueva, Coahuila

In fact, they argue, there aren’t any studies regarding the impact of a solar farm of the dimension that they are proposing in Comitancillo. “We know the impacts caused by smaller solar farms. Some studies point out, for example, the increase in temperatures between 3 and 4 degrees Celsius, along with dust and noise pollution.”

What is true, they inform, is that inside the polygon of the solar farm they will remove everything from the land, the trees, crops, and animals, community trails will disappear or be privatized. “The land will be made bare and on top of it they will install panels. No vegetation will be left,” they sustain.

Don Alberto Hernández Toledo possesses two hectares of forest in the polygon sought by Helax Istmo. “I can’t describe how fertile this land is. I have protected a large piece of land with trees, large trees (guirizhiña, guieniza, bii’, dxima, gulabere). Birds, iguanas, and all different types of species take refuge there. I am very proud of this. I protect it, even from my own people. I don’t like that they go there looking for iguanas.”

Representatives of Helax Istmo said to Hernández Toledo that if he rents his lands they will protect the two hectares of land that he has preserved.

In spite of the promise, in an informative document about the project presented to local authorities, the company specifies that in order to condition the area, “the leaser will allow Helax to carry out whatever action necessary to obtain the permits and licenses for the project, including changing the use of the soil before the Secretariat of Environment and Natural Resources (SEMARNAT).”

“We are not naïve,” the ejido member says to Avispa Midia. “Once we accept that they enter with their project, they are going to do away with everything.”

The polygon where they seek to construct the solar farm, according to ejido members interviewed for this report, is cultivated with resources from the Sembrando Vida program. “Many of the producers in this program will be affected by this project. It doesn’t make sense that now they are working to reforest the area when tomorrow they will be deforesting the area for the establishment of the solar farm,” sustains Hernández Antonio.

“To condition the area” also means doing away with the spaces of identity and memory of the community. Exactly in the polygon where they seek to build the project are six sacred sites of Comitancillo—Guamuchal, Mezquital, El Cárcamo, Laguna Hueto, Xirú, La Noria. “These are places where our history is contained, where the myths of our people are found,” he emphasizes.

In addition, they fear the disappearance of the culinary customs of the community, such as totopos, memelas, corn tamales, and beans, since there will no longer be land to plant the zapalote chico corn.

“I’m not thinking about myself. I’ve already lived. I’ve already seen many things. I think about those that come after me, my grandchildren, my greatgrandchildren, my great great grandchildren. If we let the company into the community, what will those who come after us get to know? They won’t know how to plant the land, they won’t know the iguanas, lizards, butterflies, birds, or trees. I learned from my parents how to care for these lands. That is why we defend them for those that come after us,” says Hernández Toledo. “We’ve already saved this territory once, when they tried to install a wind turbine blade factory in our common use lands, and we are going to continue doing so,” he says.

This is How We Combat the Climate Crisis?

The green hydrogen project will be financed by two funds of Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners—Growth Markets Fund II and CI Energy Transition Fund. Specifically, this second fund, CI Energy Transition Fund, is focused on projects of renewable energy in different parts of the world—Western Europe, North America, Asia, and Australia

It is advertised as a “sustainable investment” as it falls under Article 9 of the Sustainable Finance Disclosures Regulation (SFDR), a framework established by the European Union to “create” world governance in the financial sector in materials related to sustainability and energy transition, whose objectives are linked to the Paris Accords.

The company, founded in 2012, has positioned itself as the leading fund manager focused on renewable energy. It has raised around $26 billion euros from more than 150 international investors for its projects and has the ambition to raise $100 billion euros by 2030.

* For security reasons, the name is fictitious.

* Photos provided by the community of Comitancillo and Campo A.C.