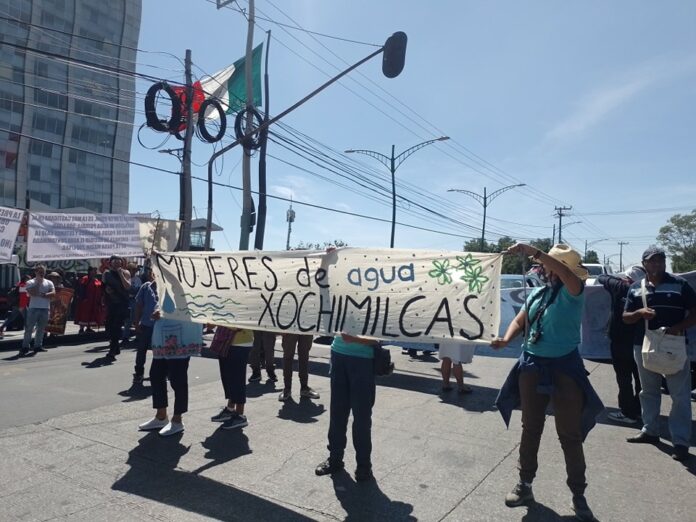

Cover photo: Members of the Assembly for Water and Life protest in front of CONAGUA in Mexico City.

The Assembly for Water and Life blamed the National Water Commission (CONAGUA)—a government institution in charge of implementing the National Water Law—for omission and complicity in the plunder of water which has caused a water crisis in Mexico that is now considered irreversible.

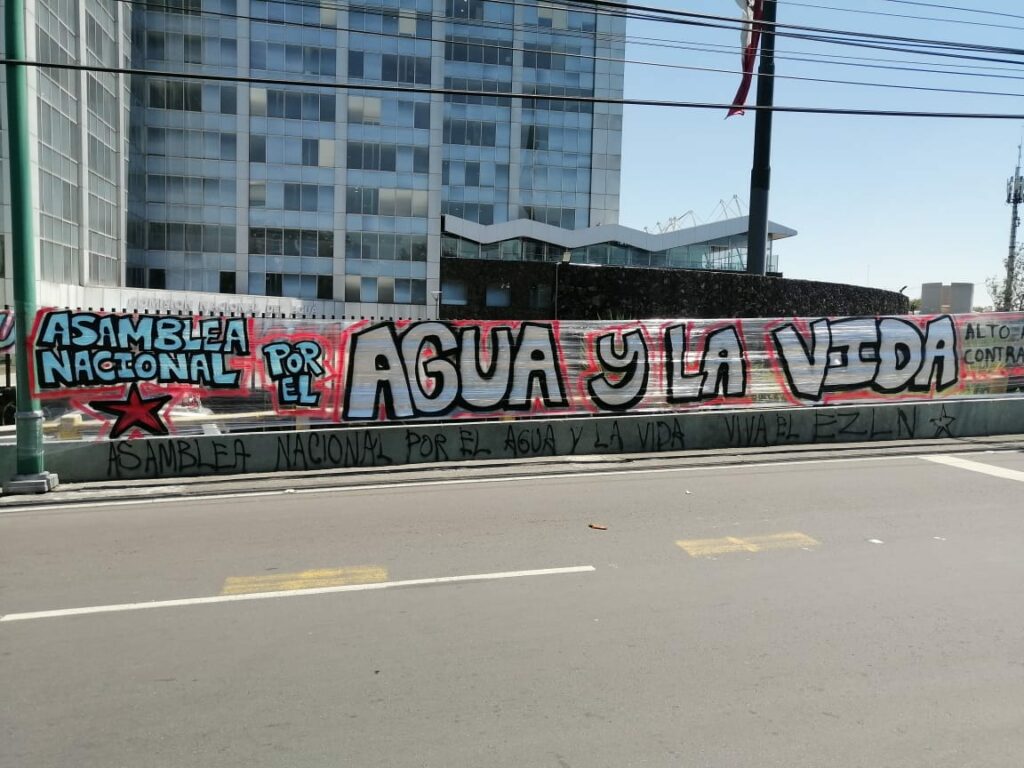

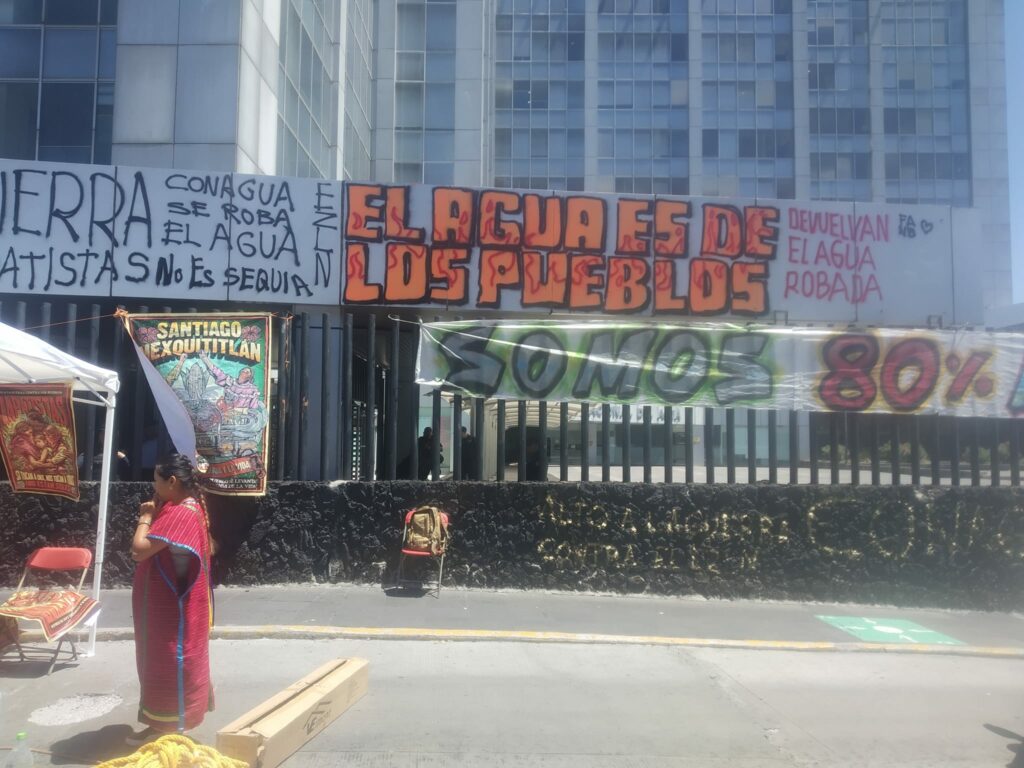

Members of the assembly gathered in front of the offices of CONAGUA in Mexico City, painting protest slogans on the building, and covering the railings with signs and banners. During the protest, members of the assembly blocked traffic at Avenue Insurgentes Sur and Avenue Universidad.

You might be interested in- Resistance Grows Against Water Privatization in Mexico

The phrase “Water belongs to the people” was written in large letters at the entrance of the building, where a press conference was also held. There, the assembly launched the “National Campaign Against War and for Life.”

In a communique, the assembly pointed out that in the 34 years of CONAGUA’s existence, they have allowed 115 of 653 aquifers to be overexploited. At 99 of those aquifers, an individual, company, or association is monopolizing the water.

The assembly also denounced the international water market opened up by the National Water Commission. For example, they have authorized concessions to banks such as BBVA who control 1.6 hectometers per year of water in the overexploited aquifer Atemajac. near Guadalajara, Jalisco. There is also the case of Banca Azteca, who holds a concession in the overexploited aquifer of the metropolitan area of Mexico City, controlling 2.2 hectometers per year of water.

The assembly emphasized that since the creation of CONAGUA on January 16, 1989, “A minimum portion of the population—equivalent to 1.1% of all water users—exploits more than a fifth of all national water.”

One fifth of the water in the country is being monopolized by a group of 966 companies from industries such as electricity, brewing, steel, agrobusiness, mining, paper, automotive, bottling, among others. Between them, they exploit 5,805 hectometers per year of water. A single cubic hectometer is equivalent to one million cubic meters.

There are also 1,537 individuals who own concessions for 2,547 hectometers per year of water and 801 civil associations that have concessions for 4,856 hectometers. “The worst thing is that without regulation or control, and enjoying government impunity, once they use the water it is returned contaminated to the oceans, rivers, towns, and communities.”

Adding to the problem is exactly that, the contamination of water throughout the country. This too seems to have become a business for CONAGUA who with the slogan, “He who contaminates pays,” promotes the discharge of toxic waste into rivers, lakes, and open land areas.

“It is fertile territory for corruption, like paying off officials who do superficial inspections, or ignoring the issues as long as they receive their respective under the table payments. Likewise, with the National Water Law, businesses can avoid a large percentage of the payments they generate for polluting, registering their concessions under different uses, which exempts them from paying the industrial use fee,” signals the communique.

The communities and organizations recalled that in 2010, the General Assembly of the United Nations adopted a historic resolution recognizing “the right to safe and clean drinking water and sanitation as a human right that is essential for the full enjoyment of life and all human rights.”

War in Defense of Water

In the voice of the Indigenous Otomíes, the assembly mentioned the Peñasquito mine, where the Canadian company Goldcorp exploits 50 hectometers per year of water. There, the company is also accused of contaminating the water of the communities in the municipality of Mazapil, Zacatecas.

The assembly explained that the water there is also being exploited by the FEMSA group, by Bebidas Mundiales and Bepensa, together exploiting 21.9 hectometers of water per year to produce sodas like Coca-Cola.

The total volume of water under concession is 39.4 hectometers per year when you add other users who are part of the Coca-Cola group, such as Nayar, Servicios Refresqueros del Golfo y Bajío, Bebidas Refrescantes de Nogales, Propimex and Inmuebles del Golfo.

In Chiapas and Tlaxcala, the same business group has also been denounced for leaving populations without water due to the overexploitation of the aquifers, “CONAGUA allows those monopolizing the water to have various concessions for different types of use, these concessions can be classified differently, and the same user can have multiple concessions via family members or borrowed names, thus avoiding paying fees by pretending to have a different type of concession,” denounced the assembly.

The assembly also spoke of the company Bonafont-Danone in the Cholulteca region, who for more than seven years operated an expired concession. The assembly accused the company of stealing water for 29 years, and of causing an environmental disaster in the form of a sinkhole in Santa Maria Zacatepec on May 29, 2021. This environmental disaster took place with the permissiveness of José Cinto Bernal, the mayor of Juan C. Bonilla, Puebla.

“Those of us who are part of the National Assembly for Water and Life, we maintain that the plunder of water is part of the capitalist war against Indigenous peoples. That is to say, a war against the vital liquid, another head of the capitalist hydra.”

For the assembly, this strategy of war against life is being orchestrated by the government of the so-called fourth transformation, where the Army, National Guard, organized crime, and paramilitary groups, are used to impose megaprojects like the Maya Train, Interoceanic Corridor, and the Integral Morelos Project.

For example, in July of 2022 in San Pedro Tlalcuapan, Tlaxcala, water defenders and community leaders Saúl Rosales Meléndez and Raymundo Cahuantzi Meléndez were arbitrarily detained and accused of a killing.

During the detention, different human rights violations were committed, “and they have been unjustly imprisoned for more than a year.” Diverse collectives condemned these violations carried out by the government of Tlaxcala against the Tlaxcalteca people who struggle to defend their territory, forests, water, and collective rights.

They also spoke out about the area “Malpais,” in Calpulalpan, where the oak forest was destroyed to install a solar farm. Also, of different populations in the municipality of Magdalena Tlaltelulco who have had to face land dispossession, “and even more dangerous, the authoritarian and violent plunder of water wells pertaining to our ejidal community.”

This criminalization of social struggle has also been documented in Puebla. The resistance won the freedom of Miguel López Vega and Alejandro Torres Chocolatl, who since 2019, were persecuted for defending the Metlapanapa River.

In the Choluteca region, the company Bonafont-Danone not only plunders the water, but they also contaminate the water of the five communities of the municipality of Juan C. Bonilla: José Ángeles, Santa María Zacatepec, San Lucas Nextetelco, San Mateo Cuanalá and San Gabriel Ometoxtla.

In mentioning the water defense in Queretaro, the assembly shared how in March of 2021 after documenting the plunder of water and the multiple irregularities incurred by public officials, the State Water Commission favored private companies, in their majority real estate companies, over the rights of the people.

“Thanks to the mobilizations, the legal files were closed that had criminalized the three water defenders after the repression on June 10, 2022, in the context of the protests against water privatization in Querétaro,”

For these reasons, the assembly requested that CONAGUA receive the petitions regarding the case of Santiago Mexquititlan. “We demand that the head of the state of Querétaro revoke the law that authorizes drinking water services to private industry, legitimizing the public force to search homes.”

In Queretaro, the repression has increased with attempts at extrajudicial killing, forced disappearance, arbitrary detention, and sexual, physical, and psychological torture, “with the understanding that the Mexican state seeks to protect national and transnational power at the cost of state violence against Indigenous communities.”

For their part, the Indigenous Otomí community residing in Mexico City, on the eve of their third anniversary of having taken over the National Institute for Indigenous Peoples’ building, now called the House of Indigenous Peoples and Communities “Samir Flores Soberanes,” condemned the police harassment, and the continued incapacity of the authorities to resolve their demands of education, work, healthcare, food, and above all, housing.

With all of this, the Assembly for Water and Life reiterated the call to the peoples, communities, organizations, networks, and collectives, to join the actions of the National Campaign against War and for Life, and to get in contact by sending an email to asambleanacionalporelagua@gmail.com.