Translated by Elizabeth L. T. Moore.

Cover image: A farmer guides us toward the mangrove region in the Central American Pacific where work is underway to build an airport. Photo: Juliana Bittencourt

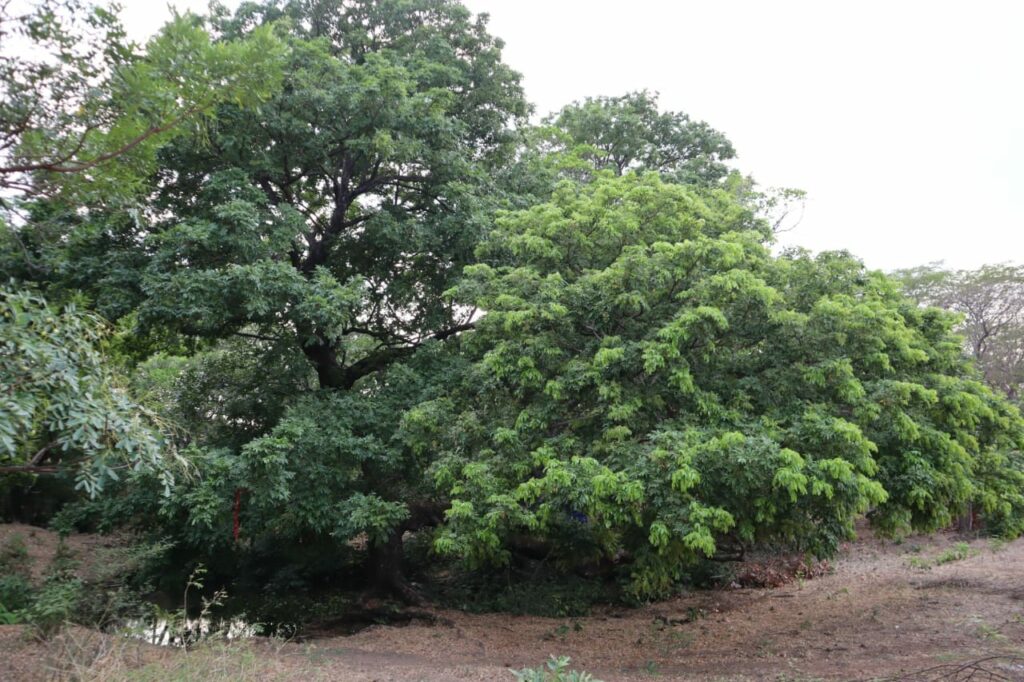

Don Elmer, a 63-year-old rural dweller, feels happy. “I cheer up when they come to sing to me,” shares the farmer about the birds chirping in the forest, in an ecological buffer zone of mangroves called El Tamarindo, a Protected Natural Area on the Pacific Coast of El Salvador.

“If they make the airport, all these birds, what are they going to have to land on?” laments Don Elmer, who makes up part of the 57 families in the Flor de Mangle community, in the Conchagua municipality, that are being displaced for the implementation of the International Pacific Airport megaproject.

According to formal complaints of the residents consulted by the team of this report, since February 8, 2023, personnel that introduced itself as part of the Guatemalan company Rodio Swissboring, hired by the Port Authority Executive Commission (CEPA in its Spanish abbreviation), began work in the Condadillo and Flor de Mangle communities, saying they would conduct a ground study in the area and move forward with the construction of a new airport terminal.

The testimonies recount how the workers entered with machinery and crew in the agricultural and housing land plots, “without authorization from the proprietors or a court order to do so,” they emphasized during the public complaints. Community members report that members of the Armed Forces and the National Civil Police are being mobilized to act as security for the company's machinery.

The workers drilled and excavated the ground, forming ditches with dimensions up to 40 meters wide, 60 meters long and more than nine meters deep. “In one of the plots of land, the ditch has come to span almost the whole area. Less than one kilometer away in this same plot are the mangroves of the El Tamarindo estuary,” says the complaint.

The rural inhabitants point out that upon finishing work in the invaded plots of land, the workers stopped and left, leaving the area unusable for agriculture and creating risky conditions, for both people and the rural families’ grazing livestock.

In March, reporting by the El Salvador media outlet MalaYerba proved that work had begun on the new airport, despite the fact that they still did not have the environmental permit currently required by law. In a report, they highlight the conduct of the CEPA director who, on national television on February 8, lied to assure that they had permits, even when the media confirmed that the resolution of the license was not made available by the environmental authorities until March 22.

“Not just Flor de Mangle will be affected. Here we have Condadillo, we have Llano Los Patos, a part of El Carrizal and also El Embarcadero,” stated Don Elmer with bitterness while he listed the populations threatened not just by the airport infrastructure, but also by what the development of this special economic zone will trigger, involving touristic, industrial and commercial complexes.

Development Pole

The team of this report traveled through the Condadillo territory in La Unión municipality, in the department of the same name, located in the eastern region where the Salvadoran government is looking to transform into a “development pole.”

To strengthen the plan, in addition to the new airport terminal, other efforts are in the works: standing out among them, so-called Bitcoin City, the Pacific Train and the modernization of ports in the strip of the Pacific coast, from Acajutla to La Unión; mega infrastructure projects that make part of Plan Cuscatlán, a government proposal that Nayib Bukele presented during the 2019 presidential elections, but that dates back to previous administrations.

“It’s a Special Economic Zone (ZEE in its Spanish abbreviation). It’s the privatization of territories. The previous administration had already launched the project by law on July 19, 2018, to establish it,” points out agroecology professor José Ángel Flores, member of the Asociación Intercomunal de Intipucá, which belongs to the Vida Digna Communication Network, an organization that brings together communities in the east of El Salvador threatened by megaprojects.

At the time, they distributed an agreement between the administration of the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN in its Spanish abbreviation) and China, which sought to invest in the development of a 2,800 square kilometer Special Economic Zone between La Libertad port, in the Lempa River, reaching La Unión port, in the geostrategic Golfo de Fonseca.

Previously, since 2014, the progressive FMLN administration was considering building El Jagüey International Airport, a project renamed and currently put into motion by Bukele in the same territory in Pacific Central America.

Without defense

As we passed through the forest, we noticed a pattern of sign posts; orange paint covers the tree trunks. Santos Cruz, a rural inhabitant of the region, mentions that they’re marks left over from an odd census in which, for days, workers from CEPA and the Ministerio de Obra Pública measured and evaluated the site for construction of the airport.

Since the first few months of 2022, Condadillo residents noticed more activity by the State workers, who in addition to taking measurements of the land, would photograph the dwellings and plots of land that belong to the rural inhabitants. For them, that added to the presence of military contingents and police, which was standardized from the month of March on, when an emergency government was declared in the whole country, justified by the rise in homicides and gang-related violence.

The residents’ situation worsened, given that various communities don’t possess deeds. Nor do they have formalized possession of the land. That means they can be dispossessed at any point, emphasized Professor Flores, who joined us on the traverse through the affected communities, while highlighting that the right to have appropriate information has been stripped away, and the populations have not been consulted.

Laws on the fast track

While we visit the mangrove forest in the ecological buffer zone of the airport project, Flores contextualizes the actions of the legislative power and environmental institutions, and emphasizes how they’re at the mercy of President Bukele, who has fast-tracked these megaprojects.

As an example, he mentions the passage of the Law of Eminent Domain of Property for Municipal and Institutional Works on November 24, 2021. In said regulations, mechanisms are established for the expropriation of properties due to “public utility or social interest,” a law approved only three days after the announcement, on the part of Bukele himself, of the construction of the mega undertaking that encompasses the so-called Bitcoin City.

According to the professor, the law omits the conciliation phase, that is to say, a space for dialogue does not exist, “while the process starts up, the Salvadoran state can go on building and installing the megaprojects until a resolution emerges. The population remains dispossessed and does not have any kind of state entity that it can turn to,” Flores maintained.

He affirms that the passed laws intend to ease the process of establishing mega investment projects. In this way, the Legislative Assembly also passed the Law for the construction, administration, operation and maintenance of the International Pacific Airport and the Law of the special regime for the simplification of procedures and administrative acts related to the Pacific Train. Both regulations have been criticized because they permit both the train and the airport to be exempt from the Law of Acquisitions and Recruitment of the Public Administration, remaining totally outside the transparency standards.

For his part, Don Elmer expresses worry about the uncertainty of his land in Flor de Mangle. He complains about the constant visits from bureaucrats, who pressure the rural inhabitants in the context of an expropriation process. Both residents of this community and those of Condadillo have publicly denounced CEPA’s pressure to sell their land at prices that they consider unfair, which has led them to reject the valuation signature; even though the countryman affirms that some families have ended up conceding out of fear.

Before the increase in threats, in October 2022, the rural residents publicly rejected negotiations with CEPA. Representatives of the two communities pointed out that the institution valued its land at an amount of $8,000 USD per manzana (equal to 0.70 hectares or 1.73 acres), though they think the true value is higher.

Santos Cruz, a farmer with land in the area, accused CEPA officials of visiting landowners to give an ultimatum. “If you don’t sign, you could end up with nothing,” the rural inhabitant said about the behavior of the state workers. “As the farmers, the poor people of the country, we’re suffering so much for megaprojects the government brings. Why not take this airport somewhere else? The country doesn’t need two airports,” he complained, maintaining that dozens of families would be left without sources of income if the project is implemented.

“Green” airport

According to the Cuscatlán Plan, the core ideas guiding the Bukele administration, constructing the Pacific Airport represents the consolidation of the first “green” airport terminal in Central America. To do so, it assures that its implementation will be based on the standards of the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) certification from the United States Green Building Council, “protecting the buffer zone and establishing new legislations for the development of ecotourism in the region.”

The International Pacific Airport, with an investment of approximately $300 million USD, intends to encompass a surface area of almost 20 thousand square meters. Even though CEPA still has not specified if it will be administered by the state or by a public-private entity, the feasibility studies were run by UDP CONSORCIO PEYCO–ALBEN 4000, property of Grupo SEG, of the Spanish capital.

According to CEPA’s projections, the airport will bring “poles of (economic) development” for the eastern zone and generate jobs for residents. Federico Anliker, president of the Commission, assures that the new airport terminal will be converted into an “air-tropolis,” a city of industrial plants, hospitality, resort centers and factories for the exportation of technological goods.

Contrary to the promises of sustainable development, the environmental impact study stresses that construction of the airport terminal poses a threat to more than 44 species of birds that live in El Tamarindo swamp.

“The impact includes the destruction of nesting sites, obstructing the flow of migratory birds, and the death of bird species and specimens that are endangered or in threat of extinction, like the Yellow-naped amazon, Orange-chinned parakeet, Pacific parakeet and the Many-colored rush tyrant,” it says, referring to the danger that looms over the fauna, where other species, like mammals and reptiles that inhabit the mangrove swamp and its ecological buffer zone, will also be affected.

According to data from MARN, El Salvador has 13 swamp ecosystems along the Pacific coast, whose surface area has reduced 60% in the past six decades. The construction of the Pacific Airport would pose a continued decrease of the area’s swamps, affecting the populations that live off the fish and the extraction of other marine species for its survival.

Despite the effects, the investigation media GatoEncerrado revealed in a report released at the end of 2022, that the chief of the Environmental and Natural Resources Department (MARN in its Spanish abbreviation), Fernando López Larreynaga, promoted less-restrictive directives to facilitate the construction of the Pacific Airport, although in September 2021 specialists of the institution designated the project as “environmentally unfeasible” for affecting a PNA and altering the swamps in La Unión area.

As Secretary Larreynaga justified, the implementation of new guidelines complied with at least 53 investment projects that had not been executed in the seven municipalities of the coastal strip, due to the fact that the environmental regulations were holding up the works. Because of that, the institution made the regulations more flexible with the objective of preparing the coastal territories, previously cataloged as “high protection,” to be home to the construction of huge infrastructure undertakings.

Integration for the dispossession

Despite the narrative spread by President Bukele, for professor Flores, the news of these megaprojects are not in the slightest novel.

“It’s something that comes from the era of Alliance for Progress,” he said referring to the long history of incorporation driven by the United States with the Central America region since the second half of the past century through agreements that were promoted by that country “to guarantee the economic policy of North America.”

The agroecologist emphasized the logistical component through which the existence of the Pacific Airport is justified, like the train and other megaprojects that seek to consolidate key infrastructure, through the use of public resources, for the operation and interest of the large capital transnationals.

“It secures everything with a more regional rationality. In this case it comes from the Maya Train in Mexico, then its extension in Guatemala (referring to the Bicentennial Train that will connect the border with Chiapas, Mexico, to Puerto Barrios on the Atlantic Coast) and then continuing with the Pacific Train in El Salvador (...) all these logistics are the extraction of natural resources of the few natural ecosystems left in Latin America, for the purpose of transforming goods.”

Flores points out the historical interference of the United States in El Salvador, which has implemented various strategies to deepen neoliberalism. The creation of the free commerce zone firmed up the Free Trade Agreement between the United States, Central America and the Dominican Republic, just as with the most recent cooperation programs like FOMILENIO II, which defined vital highway infrastructure for the later development of the specific coast.

“They’ve worked to configure the country like a small logistical passageway where the objective is the assembly, the storage, the distribution and the commercialization of goods, at an extremely low cost, without the sound judgment to avoid the depredation of the environment,” the professor upheld.