Mexico: TC Energy Accelerates Construction of “Puerta al Sureste” Gas Pipeline for Inauguration in 2025

The Canadian transnational company TC Energy (previously known as TransCanada) has announced to its investors that it has advanced significantly in the Puerta al Sureste gas pipeline in Mexico, an ambitious project meant to expand the market of natural gas exported to Mexico from Canada and the United States. This natural gas will supply the industrial parks being built as part of the Maya Train and Interoceanic Corridor megaprojects. The objective is to accelerate the construction of the project so that it is in operation by the middle of 2025, declared François Poirier, CEO of the company.

With the Puerta al Sureste pipeline, the transnational company will send 1,300 million cubic feet of natural gas daily to Mexico to fuel industrial projects in the south-southeast of the country. The project consists of a 715-kilometer underwater pipeline which connects to another 800-kilometer pipeline, known as the South Texas-Tuxpan pipeline, which is also underwater, belonging Sempra Energy via its Mexican subsidiary Sempra Infrastructure.

In a video report presented at the press conference of Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s government in July, the president remarked that “additionally, the Puerta al Sureste gas pipeline is being developed for the transportation of gas connecting Texas with Veracruz and Tabasco, doubling fuel transport capacity.”

In addition to the underwater pipeline, Puerta al Sureste includes an above ground section. According to company reports, already in August, “more than 98% of the installation” of this section had been completed. In addition, the hope is to “finish the last 3 kilometers in shallow waters during the current term.”

The president of the company stressed the importance of the importation of natural gas into Mexico, which has increased considerably in recent months. With that, he announced to his investors that the company is in conversation with the Federal Electricity Commission (CFE) to “speed up the inauguration of the project” to respond to internal demand, but also to continue its exportations of natural gas from Mexican territory principally to Europe and Asia.

Re-Exportation

According to data of the US Energy Information Administration (EIA) from 2023, Mexico’s inter-annual gas consumption grew 5%, equivalent to 3 billion cubic meters, between October 2023 and March 2024.

The importation of natural gas is mostly for the generation of electricity. According to the EIA, Mexican daily imports are around 5,894 million cubic meters. Meanwhile, internal production is plummeting. In April 2024, production fell 14.6 percent compared to 2023, reaching a minimum of 3,756 million cubic feet daily, the lowest level since April of 2021, according to the National Hydrocarbons Commission.

In an interview with Avispa Midia, Luis Pérez, a researcher from the GeoComunes collective, pointed out that “natural gas is the energy source which sustains the energy grid of the country.” Therefore, the discourse that Mexico is going to export natural gas has no basis. In reality it is a “re-export” carried out by companies like TC Energy and Sempra Energy, explains the researcher.

Pérez cautions that the network of gas pipelines being constructed throughout Mexican territory, which supply power plants, the mining sector, and industry in general, “now has a role on the global scale, due to interests in the commercialization of gas coming from the east coast of the United States,” he explains.

The member of the GeoComunes collective says that they have identified at least “eight gas exportation projects without counting various expansions. Together, these projects have a capacity to export 11.5 billion cubic feet of natural gas daily. The daily consumption in Mexico is between 8.5 and 9 billion cubic feet.”

The researcher asserts that this gas market, derived from hydraulic fracking in the United States and Canada, “is gigantic, seeking to export more than what Mexico consumes. So, it is a re-export,” where the transnational companies are using the infrastructure of Mexico to send gas to other continents like Europe and Asia.

The CEO of TC Energy does not hesitate to tell his investors of the opportunities on the horizon with increasing gas consumption in Mexico, caused by the demand from new power plants of the Federal Electricity Commission (CFE), along with investments in nearshoring, and for exportation.

“We are very optimistic about the role that Mexico will play in the North American natural gas market, both for its growing internal demand as well as its potential for exportation,” Poirier explains.

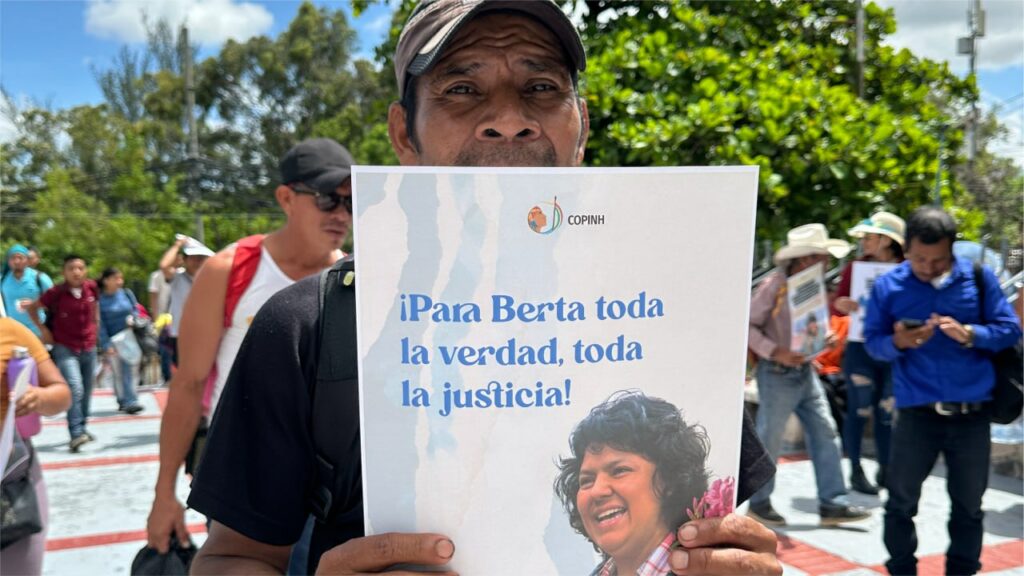

Resistance

Behind every project there is discontent, principally native communities and civil society organizations. In June, Indigenous peoples of Mexico and Canada united their voices to denounce to the Annual Meeting of Shareholders of TC Energy that the company has violated their basic rights, like the right to a consultation established in Convention 169 of the International Labor Organization (ILO).

There was no consultation with local communities for the construction of the Puerta al Sureste gas pipeline. There was no “participation of local Indigenous communities, especially fishing communities of the coast of southern Veracruz who have not been informed by the company of the direct and indirect impacts of the project on their lives,” they denounced in a statement released in June. The statement was signed by different non-governmental organizations including the Centro de los Derechos Humanos de los Pueblos del Sur de Veracruz Bety Cariño; Greenpeace A.C., among others.

While TC Energy advances on the construction of the Puerta al Sureste pipeline and shows optimism for the expanding gas market in Mexico, the Mexican government is presenting the project as a major achievement of the so-called Fourth Transformation.

In a video presented at López Obrador’s morning press conference in July, it was explained that the CFE “is arranging the largest energy infrastructure project in the history of the southeast, which aims to supply energy demands to, among other projects, the Maya Train.”

The video also explained that the government has created the conditions “to transport gas to power plants, expanding the infrastructure of the gas pipelines to the southeast. The old Mayakán gas pipeline has been interconnected with the national gas pipeline system, implying that the availability of the fuel will increase by 400 percent in the region.”

You might be interested in-- Sempra Energy: The Real Winner in Mexico’s Energy Reform