Translated by Jorge Ramirez and Ismael Illescas

Early in 2017, the United States military’s Southern Command (SOUTHCOM) and Northern Command (USNORTHCOM) strategically roamed over tactical points throughout Honduras, Mexico, and Guatemala. At the same time, the newly elected President of the United States, Donald Trump, threatened the president of Mexico, Enrique Peña Nieto, with the possibility of a military intervention if Mexico did not prove it could solve the drug trafficking issue.

The Southern Command (SOUTHCOM) is one of six unified Combatant Commands (COCOMs) in the United States Department of Defense. It is responsible for US military operations, such as the cooperation and the creation of partnerships in a region that includes 31 countries and 10 territories in the Caribbean, Central America, and South America.

The North Command (NORTHCOM) is responsible for the United States' internal defense, and covers Alaska, Canada, Mexico and portions of the Caribbean, including Cuba.

On Jan. 31, the United States Air Force (USAF) Gulfstream IV (C20-F) jet landed in the Navy hangar on the southern border of Mexico in Tapachula, Chiapas. Lori Robinson, head of the US Northern Command, Kurt Tidd, leader of the Southern Command, and Ambassador Roberta Jacobson met with officials from the Mexican Foreign Ministry. Among them was Socorro Flores the undersecretary of Latin America and the Caribbean, and Luis Videgaray, Foreign Minister. According to British media sources, Reuters, attendees asked for anonymity. Among other issues addressed at this meeting were those concerning migration and organized crime.

This meeting was held despite the increasingly tense diplomatic relationships occurring via telephone, between the governments of Enrique Peña Nieto (Mexico) and Donald Trump (United States). The latter demanding that the Mexican president and his country pay for the construction of the border wall. In addition, Trump threatened Peña Nieto by telling him that if the Mexican military could not fight the drug cartels, then he would send troops from his country to solve the problem.

It has been several days since this event, and Trump’s statements appear to be in line with the continuation of military intervention planned before 2010, according to a leak made by WikiLeaks dating back to September 10, 2010, 2010 (Latam) Mexico-100910. The document reveals that an intelligence committee from Mexico and then US ambassador to the United States, Arturo Sarukhán, held secret meetings at the Pentagon’s Northern Command facilities. On behalf of the United States stood the Department of Homeland Security and representatives of the Air Force. The leak also maintains that the then Commander of the North Command, Admiral James A. Winnefeld Jr., had ordered the evaluation of possible military assistance to Mexico that went beyond the formation of training and exchange programs.

The Mexican president denied that in the conversation with Trump there was discussion about a possible U.S. intervention in the Mexican territory. It seems that Trump’s statements and the last visit of the United States military command in Mexican territory have a broader meaning that requires the participation and cooperation of the government of Peña Nieto. Specifically, for an intervention of American military forces to join the war against drug trafficking and counterinsurgency. Since the leak also claims that Hillary Clinton has compared these events with the war in the Middle East, it follows that the war on drug trafficking in Mexico would have to be considered as a counterinsurgency war.

In the war against drugs in Mexico, where the United States has been involved, the reality cast numbers that reveal that there has been more than 200,000 dead in only one decade, which has been accompanied by the strengthening of organized crime and the increase in the flow of arms and drugs. While these leaders are struggling to exchange their most clever speeches, we know that at least 2000 weapons enter Mexico illegally every day, which involves the stock exchange that is part of the annual $10 billion amassed by the American armaments industry. We must make it clear that arms are goods that fluctuate according to the laws of supply and demand. According to a report published by the Center for Social Studies and Public Opinion (CESOP) of Mexico in 2014, it is estimated that 2000 weapons are brought to Mexico legally through one of the more than one hundred thousand permit holders who sell them in legally-constituted businesses or so-called “Gun shows” that operate along the border of the United States and Mexico. One example is the assault rifle AR-15 manufactured by Smith & Wesson (S&W), the largest firearms company in the United States. It is one of the preferred weapons by the drug traffickers, but also of exclusive use by Mexican and Central American armies. This company trades its shares in the NASDAQ stock market (National Association of Securities Dealers Automated Quotation) as SWHC. In 2016 alone, it registered 722.91 millions of dollars in its sales. Arms exports from the world’s major industries increased by 14% between 2011 and 2015, in which the United States was the world’s primary arms dealer according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI)report published in February 2016.

In addition to the illegal arms case discussed above is the armament bought by nation states. In this regard, Mexico offers an example. Between 2012 to 2015, the government of Enrique Peña Nieto increased the purchase of military equipment from the United States. It acquired airplanes, helicopters, all-terrain trucks and high-powered weapons. This acquisition was made through the Foreign MilitaryIn addition to the illegal arms case discussed above is the armament bought by nation states. In this regard, Mexico offers an example. Between 2012 to 2015, the government of Enrique Peña Nieto increased the purchase of military equipment from the United States. It acquired airplanes, helicopters, all-terrain trucks and high-powered weapons. This acquisition was made through the Foreign Military Sales Program (FMS), worth more than $1 trillion, which has been registered in a report released on 2015 via the Senate Armed Services Committee and the United States Defense and Security Agency (DSCA). This means that the U.S. military industry profits from both sides of the war, from both organized crime and the Mexican government, while more than 200,000 lives lost in this context are regarded as collateral damage, and the people who are forced to migrate are converted to “illegals.”

Thus, in talking about the war against drugs in Mexico and Central America, the flow of arms must be discussed as a fundamental pillar that sustains both organized crime and the war industry.

Another example is the increase in the purchase of arms by the countries of Central America within the context of the war against drug and terrorism. The Central American countries increased their armament and military equipment such as: Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, and Nicaragua. According to data disclosed in the report titled, “State of the Region” of the National Council of Rectors of public universities in Costa Rica, purchases to the United States amounted to 2,015 million dollars in the period between 2004 to 2014. Honduras amassed 75.3% of the region’s total ($ 1,518 million). And Costa Rica, a country without an army, totaled $142.6 million, ranking second.

SIPRI Yearbook 2015.Military expenditure 2004-2014, in millions dollars

In this context, the war on drugs and terrorism throughout Latin America presents itself as the new economic policy dictated by the international market for the military industry. It is adjusted to the guidelines of the United States’ national security, which in turn, is responsible for mega-projects with regional scope such as the Mesoamerican Integration Project. This project has created a complex web of extractivist and special zones where raw materials, freights, goods and services, all circulate, enter and exit. In this complex web, arms and drugs are also included. It is clear that for the rhythm of production to be maintained in any industry, the demands of the market are necessary. For the military industry, specifically, the best demand is found in the context of war, such as the war on drugs and the war on terrorism. Thus, the possible intervention of the United States into Mexico, has another meaning beyond ending this war. That is, in resolving the war against drugs would also mean the end of the arms market in the region.

With the military intervention in Mexico, the United States would secure its influence with the official presence of the U.S. army, as it has done in the seven countries that make up Central America (Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Belize, and Panama). These countries have had the presence of American troops under the framework of fighting against organized crime and terrorism, though this has not meant that good results have been produced.

The same day that they visited southern Mexico, the United State’s military Southern Command and Northern Command, also traveled to Guatemala where they visited the Interagency Task Force (IATF) Tecun Uman. This was created in 2013 with more than 250 military elites to combat drug trafficking, smuggling, and other activities related to organized crime in the border zones with Mexico.

The Southern Command’s visit is not the first time in Guatemala. The first time it did so officially was for the inauguration of the first Interagency Task Force (IATF) Tecun Uman, in April of 2013. It was a demonstration of a continuous cooperation of transnational security between Guatemala and the United States. General Frederick S. Rudesheim, who was the commander of the United States Army South, visited this Central American country in order to give the green light to inaugurate the training of the Interagency Task Force Tecun Uman, in San Marcos. In a press release issued before the inauguration, it was stated that the U.S. embassy had donated to the Ministry of National Defense, which included 42 tactical vehicles like the Jeep J8, that totaled 5.5 million dollars. In addition, 9.2 millions of dollars in personal and organizational equipment and 10.71 millions of dollars in the construction of base operations and logistics.

I

In speaking to Avispa Midia, Luis Solano, Guatemalan journalist and author of “Guatemala Petroleum and Mining in the Entrails of Power,” stated: “The Interagency Task Force are seeking to position themselves in main border centers of Mexico, Belize, El Salvador, and Honduras. We are talking about around seven Task Force formed in and from the United States with infrastructure, institutional scaffolding, and financing by this country.”

Despite the fact that each military Task Force depends on specialized technology such as night vision goggles equipped with heat sensors that have the capacity to view distant objects up to 2 kilometers away, as well as high-powered weaponry and tactical vehicles, drug trafficking activities have not been diminished. Solano suggest that the Task Forces remain contaminated by corrupt government structures that should have been cleaned up with the creation of the first Interagency Task Forces. He continues, “While the fall of Otto Pérez Molina’s government, and all the structures around them, was presented as a process of cleaning key institutions of the State, they are in fact the very same structures as those formed by these Task Forces. No matter how much funding there is, there has been no sort of decline in drug trafficking.”

In Guatemala, a series of arrests and extraditions of drug traffickers have been realized, yet the high command of the army and police forces who are also involved in organized crime have been left untouched. Solano continues, “Yes, there have been a lot of arrests and extraditions, but the structures have not perished, on the contrary, they are reproduced, consequently generating internal struggles. What we can discern from the case of Guatemala is the occurrence of the recycling and changes of those in power over cartels. Also, the State has an important presence and strong influence. Moreover, there are even allegations of the existence of a drug trafficking organization within the police, who is in charge and responsible for seizing cargos and giving them to other cartels.”

IHonduras is a country well known for its rich culture and natural resources, but it is also known for its high rates of killing environmental protectors and the rights of indigenous communities. The case of Berta Cáceres, who was assassinated March 2, 2016 made the world look upon this country. More than 100 activists who have been defending their territories against national and transnational high impact projects were assassinated between the years 2010 and 2016, data that contrast with the increased militarization of this country. Including the presence of the U.S. military that arrived to establish “Order and Peace.”

The South and North Commands had visited this country a day before it landed in southern Mexico. The Honduran and Brazilian ambassadors at the Soto Cano Air Base, which is located in the valley of Comayagua, Honduras, greeted them. 600 U.S. military personnel and 650 U.S. and Honduran civilians operate as a Joint Task Force-Bravo (JTF-Bravo) this base. The purpose of the visit, according to the Fuerza de Tarea, “is to strengthen the rapport between Northern Command and Southern Command over its security interests along the Mexican-Guatemalan border to fight crime.”

Although for the members of the Civic Council of Popular and Indigenous Organizations of Honduras (COPHIN), which Cáceres founded, the presence of US military on their lands, according to indigenous Lenka José Martínez COPHIN Minutes Coordinator, “has more to do with supporting transnational corporations looting our country and taking over the land for the purposes of monoculture production or for conservationist politics.”

The difficult blow that these members received, as a result of losing one of their principal figures in their struggle, has pushed them to continue with more strength. At the same time, they have recognized the high cost that that their determination can have. José Martínez indicates that “This has occurred before and during the coup d’etat. Members of COPHIN have been objects of espionage. For example, in my own home I have received a lot of anonymous death threats. Juan Orlando Hernández (president of Honduras) is one of the individuals who has great interests in the country and who is placing it in the hands of U.S. and European transnational companies. 35% of the national geography of our territories are already conceded to them. And because of this that he is strengthening the army force. The military police, for instance, has been trained by the United States.” The visits made by the commanders in Central America have strengthened the proposals launched by Orlando Hernández concerning the creation of a multinational force that can fight drug trafficking in Central America since he took office after the coup in Honduras. Yet, it looks like this was not a proposal that came into being only because of the president. Countries across Central America have simultaneously created its Task Force with the assistance and support of the U.S. for precisely similar politics: struggling against drug trafficking and terrorism.

It was in 2014 when the president of Honduras announced the creation and implementation of the activities of the Maya-Chortí Task Force at the border region of Honduras and Guatemala. During the inauguration, the president announced: “We are establishing high-level groups with Guatemala and with the U.S. We work with a high-level security group with Mexico, and with them we are engaged in this process. Likewise, we are about to begin doing so with Panama and Nicaragua, where we have established excellent relationships in matters of security.”

In Honduras, as part of the Joint Task Force-Bravo, exists the Special Purpose Marine Air-Ground Task Force-Sout[h] (La fuerza de Tarea de Propósito Especial Aire-Tierra de Marines-Sur), and the president of this country, throughout a series of denouncements of various NGOs and civil society, assured that the sovereignty of his country was not being violated. Orlando Hernandez on April 2015 said, “I want to make something clear, Palmerola (Soto Cano Air Base) is Honduran territory, Palmerola is a Honduran military base and nobody else, let there be no doubt about this to anyone, either in Honduras and outside of Honduras, that it is Honduran territory.”

Apart from from the Joint Task Force-Bravo exists the Special Purpose Marine Air-Ground Task Force-South in Honduras. And despite the series of denunciation of various NGOS and civil society, the president of this country assured that the sovereignty of Honduras would not be compromised/violated. On April 2015, Orlando Hernandez said, “I want to make something clear, Palmerola (Soto Cano Air Base) is Honduran territory, Palmerola is a Honduran military base and nobody else, let there be no doubt about this to anyone, either in Honduras and outside of Honduras, that it is Honduran territory.”

Since December 2012, Dr. Adrienne Pine, professor of Anthropology at American University, has denounced the Soto Cano Air Base, which was utilized for the coup d’etat executed in 2009, and during the government of Manuel Celaya. She states, “the U.S. always says the same thing, that it isn’t our base, and its Honduras’s base and we’re simply invited. We know this to be lies.” Likewise, the professor assures that with her colleague, the anthropologists David Vine from the American University, they have identified, “13 bases or installations within Honduras that are constructed or financed by the United States: Soto Cano; Caratasca, Guanaja, La Venta; Mocoron, El Aguacate, and in Puerto Castilla there are three types of advanced operating bases used for operations in Iraq; Puerto Lempira; La Brea in Rio Claro; Naco; in Tamara there is a training area; and Zamorano is an area for firearms training.

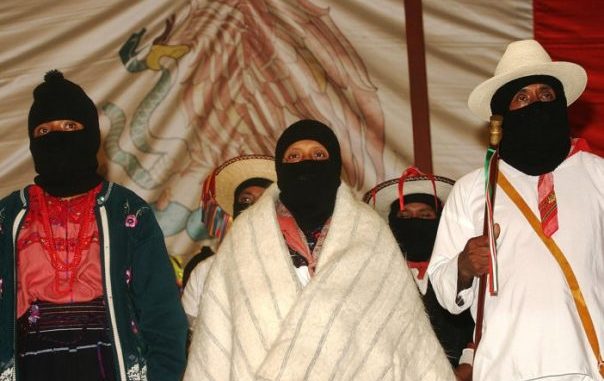

When the indigenous Lenka was asked what he thought about the presence of the U.S. military in his country, he said, without hesitation and with great certainty, that, “like the Zapatista brothers say, it is a definitive war waged against indigenous peoples who they have not been able to exterminate. The presence of the U.S. in Honduras is geostrategic because it seeks to ensure that companies can finish plundering our peoples with the Mesoamerica Project (Proyecto Mesoamérica), but it is also building more bases because it wants to attack other brothers and sisters in the same struggle in other countries in Latin America. If we do not stop these projects, the earth will be end up being assassinated within a period of 30 years because these projects are of death, this is the reason why the Lenka territory is being militarized.”

Martinez is an elder, with great wisdom and committed to his people and their organization. He understands that they can take his life at any moment, but he isn’t afraid. He fears more for those around him in his organization who are much younger, and no more than 20 years old. “We are in the eye of the hurricane of transnational corporations. The government is complying with the United States, the European Union, the World Bank, and the International Monetary Fund. But we have to continue the struggle, with our knowledge and our indigenous wisdom, because this is a war of extinction. For the United States, we as indigenous people represent a danger to capitalism, and we are the enemies because we don’t believe in their discourse of development. It is a development that is responsible for the climate change that our Mother Earth suffers.”