Cover image: Accompanied by the United States Ambassador to Mexico, Ken Salazar, and another 100 diplomats, the then Secretary of Foreign Affairs, Marcelo Ebrard, shows off Puerto Peñasco, the largest solar farm in Latin America, part of Plan Sonora. February 2023.

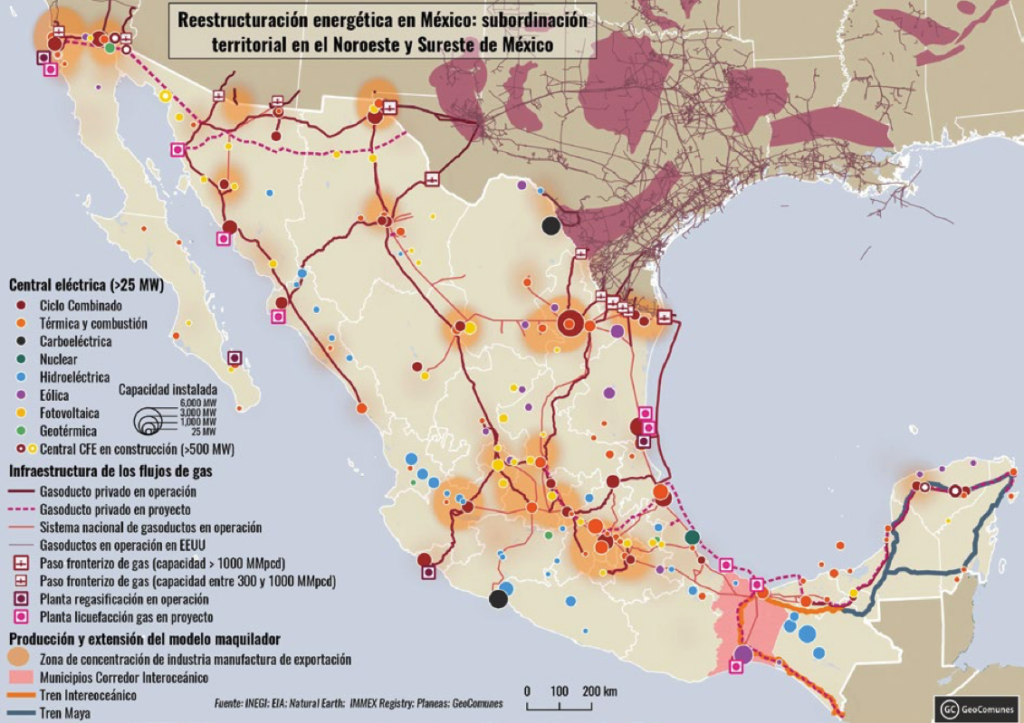

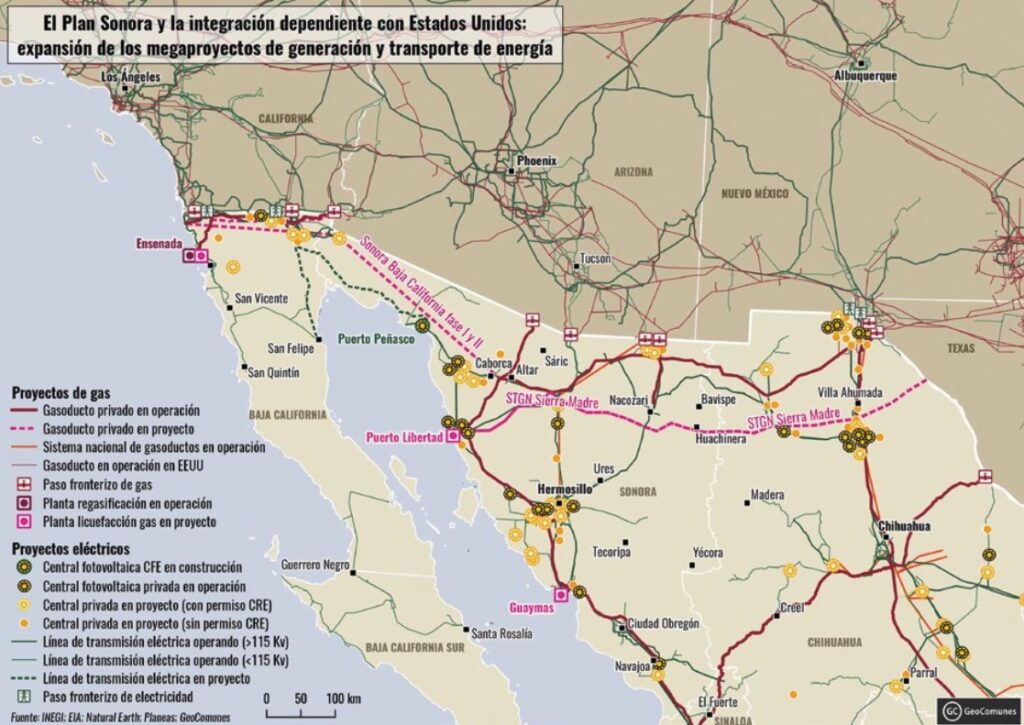

In spite of the official statement saying that the construction and operation of energy, transportation, and industry infrastructure being pushed in the southeast and northeast of Mexico responds to questions of national sovereignty, a study carried out by the collective GeoComunes shows that these projects strengthen a logic of territorial subordination to foreign capital, principally of the United States.

According to the report, this is the logic of nearshoring—a policy that seeks to move extractive and manufacturing industries that require extensive natural resources, energy, and labor to the US-Mexico border region.

In northeast Mexico, including the states of Sinaloa, Sonora, Baja California, and Baja California Sur, the researchers highlight the so-called Plan Sonora is a “new link in Mexico’s energy subordination.”

The report explains that one of the principle objectives of the plan is to strengthen certain sectors of the US economy in order to combat its current disadvantage in relation to Chinese industry. Two strategic sectors demanding developed infrastructure stand out: the fabrication of microprocessors and electric car factories.

Key United States Industries

“The Plan Sonora is a project that in spite of being presented as serving sovereign interests, clearly includes neoliberal commitments to US policy: the T-MEC (US, Mexico, Canada Free Trade Agreement), the Chips and Science Act, and the so-called Inflation Reduction Act. These three recent policies seek to incentivize the consumption of electric cars,” says members of GeoComunes during the presentation of their report.

In their analysis, GeoComunes emphasize that the United States seeks to attract two of the three most profitable stages in the production of microprocessors, in an international competition with China to slow down its presence in this sector. This means infrastructure development in northeast Mexico that “worsens the extractivist and dependent character of the border region.”

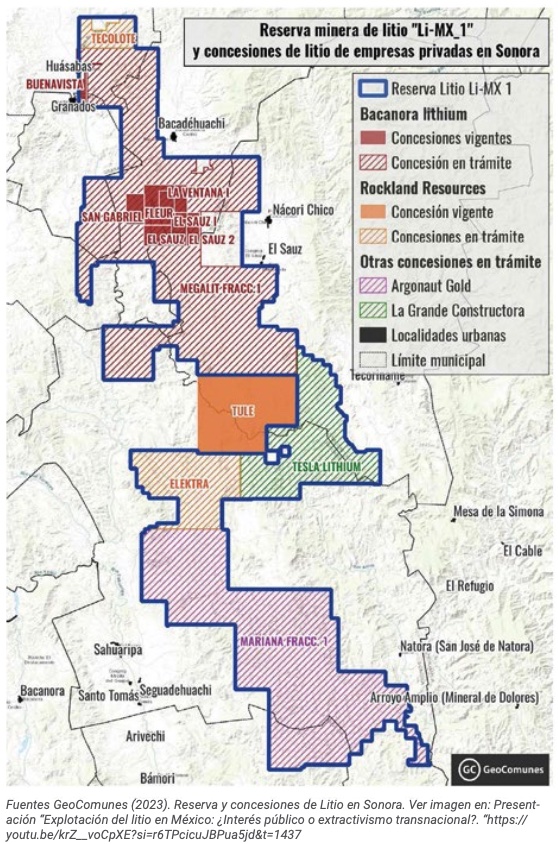

In the transformation of the energy grid for the automotive industry, GeoComunes emphasizes that “Plan Sonora adds projects that continue the agreements of the T-MEC, like committing the lithium in Mexican subsoil to supply the US automotive production lines.”

As such, the Mexican government and its infrastructure projects serve the production of US electric cars. And due to the relevance of minerals for the production of these cars, the GeoComunes collective stresses the role of the state company, LitioMx, through which Mexico will regulate private investment in lithium extraction.

“Sonora has the most extensive lithium deposits in the country, which in September of 2023, ceased to be under the control of the Chinese company Ganfeng Lithium. This happened as a result of the government canceling the company’s concession, being the only reserve the Mexican Geological Survey had decreed for the exploitation of this mineral in the country,” emphasizes the report.

Mining, Environmental Risks, and Opacity

In the analysis of the energy reconfiguration and production lines, GeoComunes highlights that lithium isn’t the only mineral needed for the production of electric cars.

“We must pay attention to the expansion of steel, aluminum, and copper production lines, mining that already has an important presence and socioenvironmental footprint in the northeast region,” contextualized the collective during the presentation of the report.

For the investigators, the Plan Sonora promotes mining extraction in the region, an industry which has already proven to be a risk to the environment and natural resources.

Suffice it is to say that, on August 6, 2014, there was a spill of 40 million liters of acidulated copper sulfate in the Bacanuchi and Sonora rivers. The ecocide, which affected more than 22,000 people, was the fault of Grupo Mexico, one of the largest mining companies in the country which to this day has not complied in remediating the environmental damages.

Ecocide in the Sonora Rivera, which took place in 2014, following a spill by Grupo Mexico.

For GeoComunes, it is alarming that the renewed impulse in mining for the components of batteries and electric systems for electric cars is being presented beneath the “false argument that it is necessary extraction to fight climate change.”

Compared to a conventional gas-powered car, the production of an electric car requires six times the amount of metal, principally copper, graphite, and nickel. The International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates that it could duplicate the copper demand between 2020 and 2040.

It is also worrying that Plan Sonora has been unveiled “little by little,” through informal declarations and without a guiding plan that clarifies its territorial scope, its different components, and the possible effects it might have on the environment.

Militarization

According to the researchers, there is a common factor in the different projects of territorial reorganization being pushed by the current administration of Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO). That is, “the presence of armed forces as administrators, builders, and security forces of infrastructure projects.”

GeoComunes explains this situation to be controversial and worrisome, because of the very little transparency and information of the plans of the federal government “in relation to this project and the militarization of the region.”

One of the many strategic projects of Plan Sonora that are in the hands of the armed forces is the expansion of transportation infrastructure, like the makeover of the Guaymas Port. This project began in 2022 and seeks to convert the port into a “modernized center of distribution that can move 3 million containers, competing with the US port of Long Beach, California.”

With this modernization, an administrative change was also made. The Guaymas Port will now be managed by a decentralized company of the Secretariat of the Navy, who also will manage the airports of Obregón and Guaymas, both in Sonora.

“The only information on the matter is what was given in the press conferences of the president of the nation and the government of Sonora, the heads of the Secretariat of the Economy and Foreign Affairs during their tours of the region, and mentions from the US government, which more often than not are ambiguous, brief, and even contradictory,” explains the analysis.

In addition to energy, mining, lithium, and electromobility, the Plan Sonora includes human capital and state of the art infrastructure, “the latter, being the construction of six scientific parks.” In other words, the idea is to strengthen the industrial corridors that “imply risks in industrial, environmental, and economic security” for Mexico.

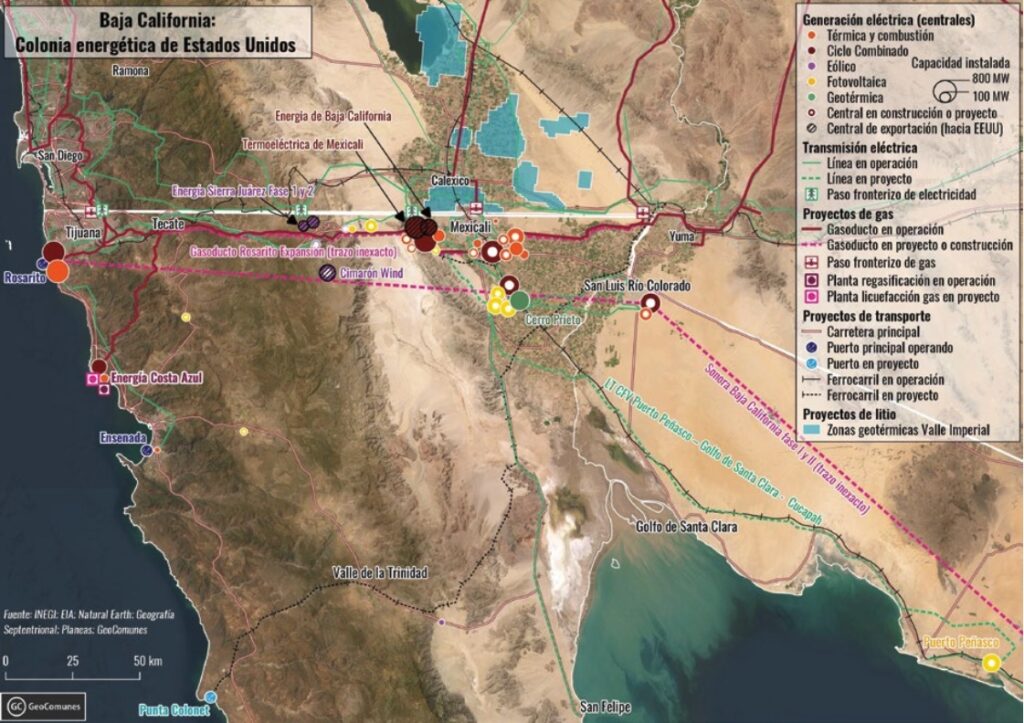

Baja California, a US Energy Colony

If the northeast region, according to GeoComunes, represents the energy subordination of Mexico to the United States, the territories and natural assets of Baja California stand out, where projects have been expanded that constitute a North American “energy colony.”

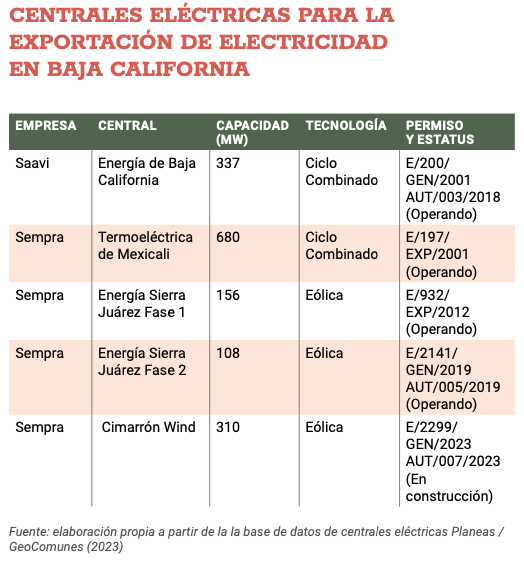

The researchers point out that Baja California currently generates 1,281 megawatts dedicated to the exportation of electricity. Furthermore, infrastructure is being built to provide an additional capacity of 310 megawatts. This is relevant because 90.5% of the electricity exports are generated in this region.

GeoComunes contextualizes that in its totality the electricity generation for exportation is the property of private companies that are directly linked to electricity border crossings. “According to data from CEC (California Energy Commission), as a whole, in 2022 these export plants sent 4,209 GWh to the state of California,” the report details.

This exportation of energy, especially from renewable sources, is expected to increase in the coming years, with California recently approving a law establishing that for 2045, they will only consume electric energy from renewable sources, “which may support the installation of more projects to import energy classified as “clean” from Baja California and Sonora,” the report states.

In the northeast they are also projecting to install energy storage systems composed of battery farms to compensate for the intermittency of renewable energies, such as the battery farm promoted by the company Sempra in Mexicali, Baja California.

The Role of Sempra

The Plan Sonora is linked to the predominance exercised by the North American company, Sempra, whose investments are spread out in different sectors of energy generation. During the last two decades, Sempra has expanded widely in Mexico, particularly in the border region, “together with the energy infrastructure in a magnitude that, in the particular case of Baja California, has arrived to determine a great portion of the local energy metabolism,” sustain the researchers.

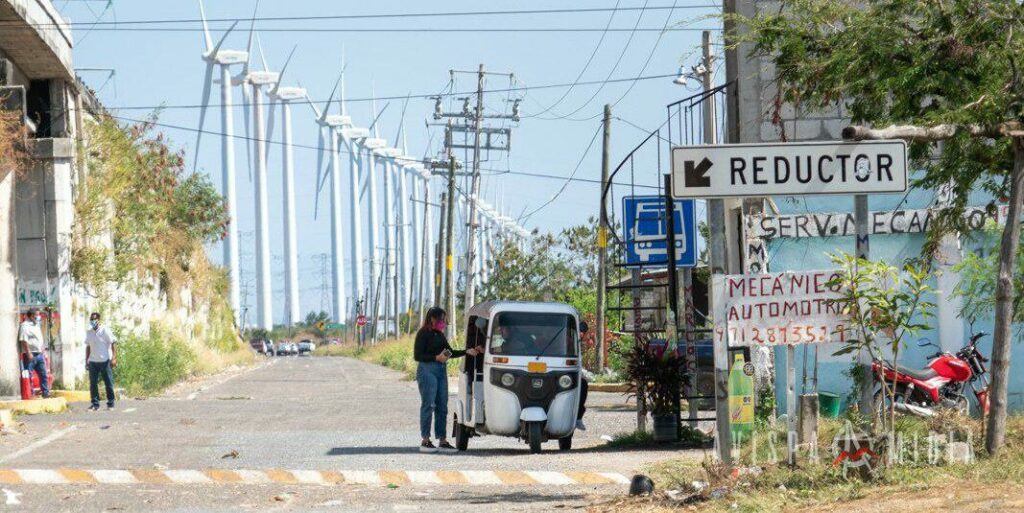

Sempra possesses infrastructure for electricity generation via fossil fuel combustion and renewable sources. The wind energy park, Energía Sierra Juárez, in the mountains close to Tecate, Baja California (IEnova)

To dimension the role of Sempra in Mexico, the researchers detail that the company is the owner of seventeen gas pipelines—with more than 2,900 kilometers of pipeline operating and 200 km currently in construction. They also own oil and liquefied natural gas storage terminals, residential methane gas distribution networks, as well as combined cycle, solar, and wind power plants, which together represent annual earnings of nearly $400 million dollars.

Sempra is one of the companies that benefited the most from the opening up of the energy sector to private investment, which took place during the 1990’s principally in methane gas, which quadrupled its assets after the energy reform of 2013.

Currently, in spite of Sempra having only 5% of the electricity generation capacity connected to the Baja California Electric System (SEBC), it maintains control of 74% of the electricity exportation capacity, and 100% of the gas pipelines.

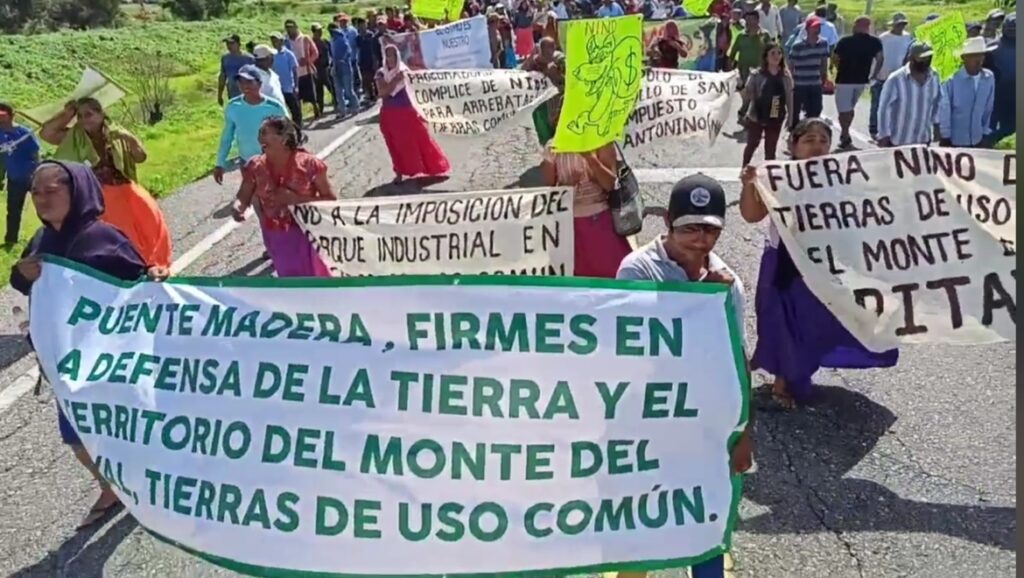

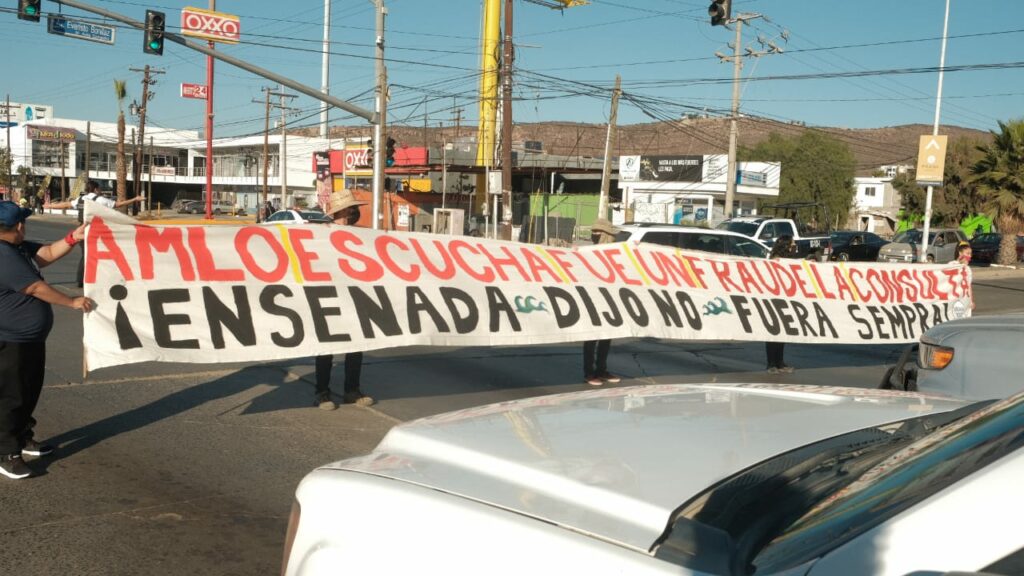

Protest against the results issued by the Ensenada City Council regarding the neighborhood consultation to determine the expansion for the Regasification terminal, Sempra, Energía Costa Azul.

It should be stressed that Sempra also controls 100% of the land and maritime border importation points through which methane gas is imported to Baja California. 81% of the generation capacity connected to the SEBC and 80% of the capacity for electricity exports that are not connected to the local grid depend on those importation points. This confirms Sempra’s predominance in the sector.