Photographies Santiago Navarro y Aldo Santiago

The enactment of the Law of Protected Areas has criminalized communities that have inhabited the Maya Biosphere Reserve (RBM) for decades, communities who have rights that were in place prior to the creation of the area. At the same time, conservation NGOs, in coordination with the Guatemalan government and the United Nations, have implemented various models and programs to combat climate change. These initiatives reinforce the discourse that promotes the eviction of peasants inhabiting the lands in northern Petén.

The Destruction of Community Models

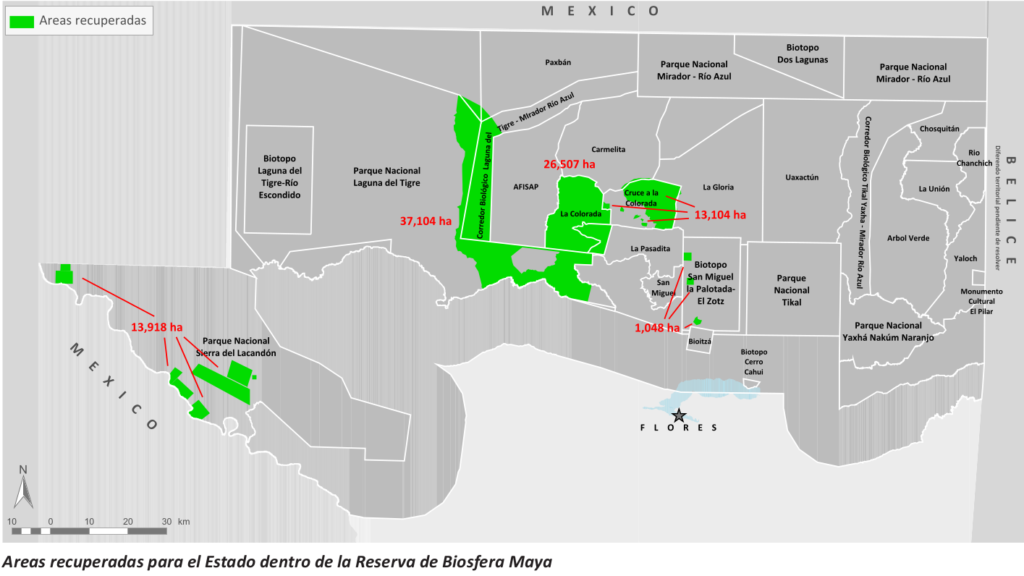

As a result of the Guatemalan State's policy to “recover governance” in areas designated for conservation projects and the sale of environmental services, numerous communities have been violently expelled from the region. This is most recently illustrated by the case of the community of Laguna Larga, who lived for almost two decades in the RBM Multiple-Use Zone.

Violent evictions of communities like La Florida, El Picudo, El Vergelito, Cruce Santa Amelia and Laguna Larga have taken place since 2007. Between 2009 and 2011 in particular, the intensity and degree of this threat led communities to denounce the clear policy of forced displacement.

Some communities, such as Pollo Solo and La Mestiza, currently have eviction orders and judicial processes underway. They are also the target of constant threats and violence, not only from RBM administrators—including the National Council of Protected Areas (CONAP) or the Nature Defenders Foundation—but also from public officials.

“The municipality, Ministry of Health and Ministry of Education are working together in the area; there is a deliberate strategy to harass the population”, denounced community members from Laguna del Tigre National Park (PNLT). The government's actions—its checkpoints and its negligence regarding basic services—limits sustenance activities for communities living in the region.

Read Part I ⇒ Guatemala: Petén at the center of the sustainable development plans of the NGOs

These testimonies concur with the experience of Laura Hurtado, director of Action Aid Guatemala, who says “the State has been ineffective in fulfilling its responsibilities; there has also been corruption and the use of violence. CONAP, the environmental authority, punishes a community member who extracts firewood more severely than a rancher who cuts down hectares to set up his farm”, the researcher says. In the history of community organizational processes, the destruction of Centro Campesino-the agro-industrial cooperative-is one of the most painful experiences in the memory of communities in the PNSL. In 1976 came the peasants who would found the Yaxchilán community on the banks of the Usumacinta River. However, by 1981 they were violently displaced by the Guatemalan army in the context of counterinsurgency in the Petén.

According to a report by the North American Congress on Latin America, after the Law of Protected Areas was approved (during the final years of the internal armed conflict), the world's largest conservation organization—The Nature Conservancy—subjected Centro Campesino peasants to extraordinary pressure to sell the Yaxchilán area. For years, the peasants refused to sell this area, as they rebuilt their community on neighboring lands.

In 1998, USAID granted US $450,000 to The Nature Conservancy to complete the purchase of over 10,000 hectares in Yaxchilán. Only 36 of 198 cooperative members signed this contract, in a context of threats and intimidation by the Nature Defenders Foundation.

According to community testimonies, after ten years under the management of Nature Defenders Foundation, these lands were devastated. The inhabitants of Centro Campesino blamed CONAP's corruption, in collusion with the Nature Defenders Foundation, for allowing illegal logging in the forests. So in 2008, the community started a reforestation process. Meanwhile, the Guatemalan State manufactured a discourse to criminalize them, calling them invaders, in order to justify evicting them.

Due to the strong organization of the cooperative, which even initiated a legal battle to cancel the deed of the sale of Yaxchilán, the government resorted to illegal strategies to force their displacement.

“They found a way to insert people working for CONAP and the Nature Protection Division (DIPRONA, by its Spanish acronym). They are like police, armed and everything. They infiltrated the community as peasants looking for work, but their objective was to gather information”. So recount the testimonies collected by Avispa Midia in the areas surrounding the PNSL.

“They found it easy to introduce gunmen, and they sent them on April 22, 2013. They killed five people who were critical in the community's organization: people who coordinated in education, the church, the land issue, and the local Community Development Council (COCODES, by its Spanish acronym). At the scene of the crime, they left a document framing other community members, which sparked internal conflict within Centro Campesino. The threats and violence unleashed after the murders led to the gradual displacement of 94 families”,

REPORTED PNSL COMMUNITY MEMBERS, WHO REQUESTED TO REMAIN ANONYMOUS TO AVOID RETALIATION.

“As soon as people left they installed a military detachment. The residents of Centro Campesino had a strong organizational process through cooperatives. This was an obstacle for the development of businesses on those lands, where they want to build hydroelectric plants, extract oil and water and promote tourism and plantations”, said PNSL community members.

“We are certain that it was a strategic eviction on the part of the State. It reminds us of the 36 years of war we lived through, because they are using the same methods to kill us: Taking water away from the fish is the only way to kill the fish. It's the same idea. They take away our land, and they are taking away our right to live”, peasants say. They also expressed anxiety about the constant threats from security forces, both public and private, who patrol the area.

Conservation: A Million-Dollar Bet in Guatemala

Community forest concessions in the Maya Biosphere Reserve, which are based on the production of raw materials for export, are the organizational base upon which a model of reference is being built. The objective is to use this model from the lowlands of Northern Guatemala to implement the Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation strategy (REDD+) throughout the Central American country.

Although the concessions were initially financed by the United States Agency for International Development through conservation NGOs, in recent years, corporations such as Ford (automobiles) and Cargill (agribusiness)—representing two of the main industries responsible for Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Emissions—have increased contributions, in order to keep the concessions operating under the umbrella organization, Association of Forest Communities of Petén (ACOFOP).

Read Part II ⇒ The commercial architecture of conservation in Petén

Since the late 1990s, Mesoamerican countries have carried out experiments in the implementation of Payment for Ecosystem Services programs (PES). Peasant and indigenous communities in the region have voiced repeated criticisms of these programs. These include: the lack of adequate opportunities for free, prior and informed consultation in the planning and implementation of projects; and the weakening of ancestral practices of forest management and governance. The latter is the result of the application of PES programs and the obstacles to native communities' territorial recognition processes—since local governments want to maintain ownership of the land in order to monopolize the eventual income derived from REDD+.

According to an October 2016 bulletin published by the World Rainforest Movement (WRM), the largest and most expensive REDD+ project in Central America is being implemented in Guatemala. It began in 2009, when the World Bank's Forest Carbon Partnership Facility (FCPF) granted US $200,000 to start preparation of the REDD+ National Readiness Preparation Proposal (R-PP).

The FCPF approved the R-PP document in 2011, and disbursed $US 3.6 million to the government of Guatemala. Additionally, Guatemala received contributions from USAID and the Global Environment Facility (GEF) in the amounts of US $5 and $44 million, respectively.

In April 2014, the Guatemalan government received more money by signing a technical cooperation agreement with the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), an implementing partner of the FCPF. With this agreement, the Central American country received an additional US $250 million.

The same WRM bulletin highlights that Guatemala was one of the first experimental laboratories for the implementation of PES projects. “In 1988, US energy company Applied Energy Services signed a contract with the NGO, CARE. The contract was to implement the first forestry project in the world specifically financed to offset GHG emissions. By investing in 12 hectares of eucalyptus and pine plantations in the Guatemalan highlands, the project would offset the emissions resulting from the construction of a 183-megawatt coal plant in Connecticut, United States. The program was a failure and contributed to an increase in the US's greenhouse gas emissions”.

Transformations

The enactment of Decree 4-89 in Guatemala marked the beginning of modifications in the local legal framework, which today enable the implementation of the REDD+ strategy in the RBM. This is legitimized through the Climate Change Law.

The decree establishes that CONAP, the National Forest Institute (INAB, by its Spanish acronym), the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Food (MAGA, by its Spanish acronym) and the Ministry of the Environment and Natural Resources (MARN, by its Spanish acronym) will be the institutions responsible for ensuring “the conservation of forest ecosystems and the promotion of environmental services that reduce GHG emissions”.

In turn, the law establishes that MARN will manage carbon markets, for which it must create the Unit for Greenhouse Gas Emissions Reductions and Removals Project Register. This entity's task will be to monitor REDD+ projects. The Climate Change Law is the product of years of consultation with the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and Rainforest Alliance—who identified and filled legal gaps in order to facilitate the implementation of REDD+.

In 2009, the Guatemalan State formalized the Climate Change Technical Unit at MARN to head development of the national strategy to reduce deforestation, which includes the REDD+ mechanism. However, the legal framework to implement the PES has transformed and been refined since enactment of the Forest Law in 1999, which promoted economic incentives for reforestation and forest management projects.

Pushing Forward REDD-plus, a document prepared by The Forest Dialogue (committee of experts from Yale University), highlights a 2010 reform to the Guatemalan legal framework: the creation of the law for the Small Stakeholders Incentive Program (PINPEP, by its Spanish acronym), directed by INAB.

This program offered to grant incentives even if landowners did not have property titles. Approximately US $40 million were channeled annually through the Global Environment Facility, which was established in 1992 at the Earth Summit, through a partnership between the World bank and European cooperation.

At the same time, INAB manages the PINFOR program for protected areas. By 2017, it had established more than one million hectares of tree plantations, “forests” managed for protection and production. PINFOR continues to operate through the work of NGOs such as Rainforest Alliance—which even certifies lands with oil palm in southern Petén.

“The experience in Guatemala shows how national processes interact with market conditions. Because pilot projects implemented by civil society could choose to work mainly with voluntary markets, there is considerable pressure on the government to develop a national strategy and establish sub-national reference levels to avoid the ‘leakage’ of emission reductions to other countries”, cites the report by The Forest Dialogue.

In addition, CONAP's operational framework makes it possible to transfer the responsibilities of protected area management to private actors. It also allows the use of financial mechanisms, such as the one established by the Fund for the Conservation of Tropical Forests—a product of the debt-for-nature exchange between the governments of Guatemala and the United States. This 2006 agreement was for US $4.9 million over a period of ten years. Managed by The Nature Conservancy and Conservation International, it provided vital funding for the execution of CONAP projects in four priority regions in Guatemala: the Maya Biosphere Reserve, the Western Volcanic Belt, the Cuchumatanes Region, the Motagua–Polochic system and the Caribbean Coast.

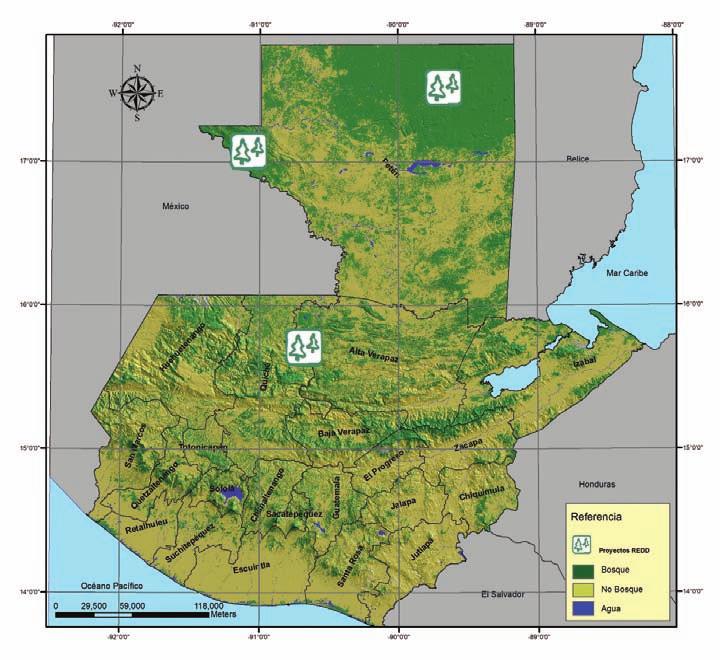

Guatemala is currently implementing three REDD+ pilot projects. However, Pushing Forward REDD-plus underscores that it is a disadvantage that these projects are not representative of the national situation. These programs, developed and implemented in coordination with NGOs, are:

1) GuateCarbon forest concessions project in the RBM, promoted by the Association of Forest Communities of Petén and Rainforest Aliance.

2) Sierra del Lacandón National Park project, promoted by the Nature Defenders Foundation, Oro Verde and Rainforest Alliance.

3) Lachuá National Park project, promoted by the Laguna Lachuá Foundation and the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

GuateCarbon: Trading with Forests

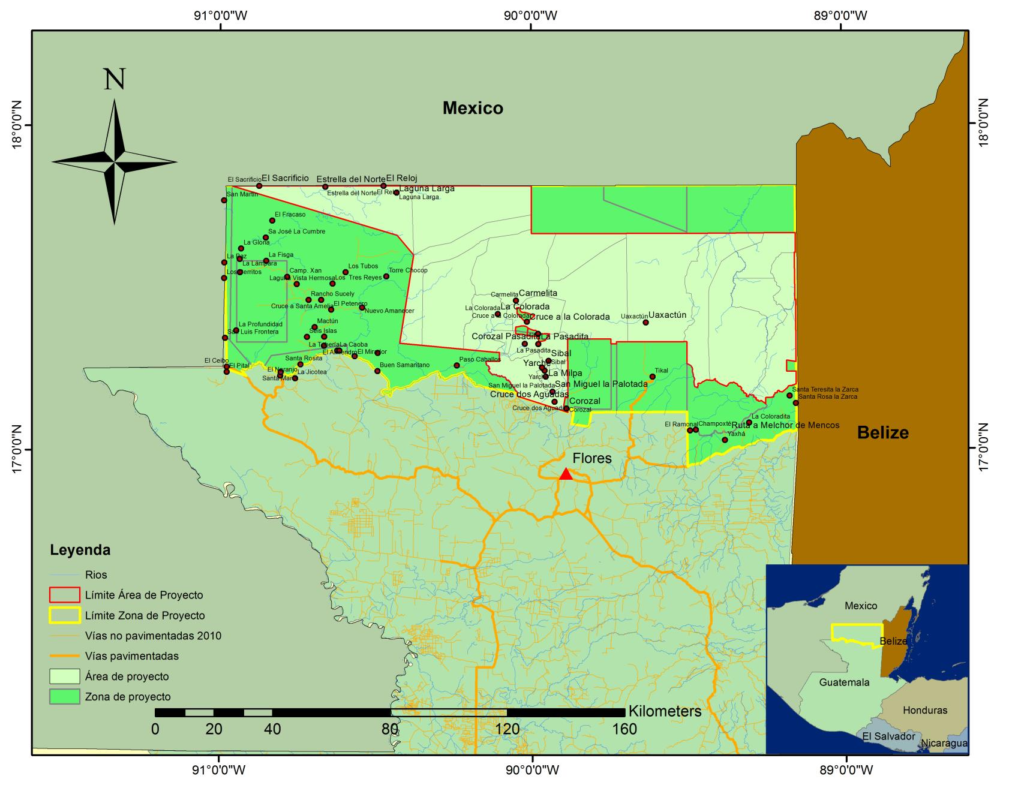

The project, “Reduced Emissions from Avoided Deforestation in the Multiple Use Zone of the Maya Biosphere Reserve in Guatemala”, was created in 2006. After going through different stages, it is currently promoted as GuateCarbon. With assistance from Rainforest Alliance, Wildlife Conservation Society, Agexport and ACOFOP, as well as funding from USAID and IDB, GuateCarbon aims to start selling carbon credits for 30 years.

The aim is to sell pollution permits generated in 721,000 hectares of the RBM multiple-use zone. In addition to community and industrial forest concessions, this area also houses the communities of Estrella del Norte, El Reloj, El Sacrificio and El Jaguar, which—like the evicted Laguna Larga community—are considered illegal.

GuateCarbon is part of the National Action Plan against Climate Change that Guatemala drew up in 2015 with the aid of IDB consultants. Ratified by the Secretariat of Planning and Programming of the Presidency in November 2016, the plan creates the conditions to reap the benefits of forest carbon—through a legal and technical framework designed to access international markets.

In this million-dollar plan to reduce contamination, Guatemala committed to reducing 12 million tons of carbon dioxide (CO2), more than half of which GuateCarbon will “absorb” by making 1.2 million carbon credits available.

In July 2017, one month after the community of Laguna Larga was destroyed, each carbon credit issued by GuateCarbon was valued at just over US $3. At this price, project officials calculated receiving US $3.84 million. “We hope that clients not only see carbon, but also see biodiversity, community development, forest cover. Last year, the payment for some credits was US $17 each”, announced project operators to the Guatemalan press.

For the 30-year period in which GuateCarbon will operate, from January 30, 2012 to January 29, 2042, an estimated 38 million carbon credits will be issued. With these credits, the expectation is to receive over US $122 million from the sale of pollution permits to companies throughout the world.

However, there is disagreement about tenure rights in regards to who receives the income from the sale of carbon. “What benefits will communities receive, if not direct income for their REDD+ actions? If payments for ecosystem services are made, who will receive the money—the government or communities? Forest concessions have a concession contract; they are not owners. Whoever receives the money should be the owner, but the concessions do not agree”, reflects Rosa María Chan, a former government official who highlights this still unresolved point of contention between the State and forest concessions.

“They tell us that the money also comes from Germany, that there's a fund from different countries assigned for the care and protection of these areas. But this money legally does not reach the communities, where it should go. It stays in the offices of these institutions that are in charge and does not go any further”, says Ignacio, a peasant from the community of Nueva Jersalen II in the PNSL. He has denounced the Nature Defenders Foundation's invitation to communities of the region to participate in REDD+ projects.

“They proposed an incentive to us, and it was a nice amount. They told us they would give us money, but that we had to sign a document. They are very sly; they say that with that money we can build a school, a classroom. But once received, that money takes away our right to use this beautiful forest, which we want to be communal”, shares Ignacio. He and his community protect the forest and surrounding bodies of water without any payment.

The Alternative Proposal and Government Intransigence

On September 26, 2016, dozens of peasants gathered in the Guatemalan Congress to present the Alternative Proposal for Integral and Sustainable Development. The proposal is focused on securing tenure for the 40 communities living in the PNLT and PNSL—both on the Mexican border.

In a room packed with local and international media, government officials—including high-ranking military officers—showed a friendly attitude. This was very different from their usual treatment of peasants, for whom this moment marked the end of a process that began in 2008. It also marked the beginning of a new stage in their struggle for the recognition of their communities in the Maya Biosphere Reserve.

Among the main demands in the document to the Guatemalan State, those that stand out are: to recognize, ensure and guarantee the continued residence of communities in Sierra del Lacandón and Laguna del Tigre; to recognize them as Multicultural Communities (based on the current plots that communities possess); and to commit to respecting all of their rights as guaranteed under national and international law.

Furthermore, the communities demand resettlement and reparation of damages for the displaced communities and families of Centro Uno Macabilero, Pollo Solo and Centro Campesino in Sierra del Lacandón, and El Vergelito and 47 families from La Mestiza in Laguna del Tigre.

The communities' most important demand is that they be granted collective property rights that ensure their continued residence in the protected areas. From their perspective, collective rights will allow them to prevent the individual sale of lands—and thus avoid land grabbing of large areas by actors and industries with economic and political power.

Cooperation?

In 1997, CONAP tried to regulate human presence in the RBM area. To this end, it created the Cooperation Agreements in partnership with the Nature Defenders Foundation. Communities denounce that the agreements were not mediated by dialogue processes and were decided unilaterally.

The reality is, no community that has signed a Cooperation Agreement is guaranteed permanence in the area, because—according to CONAP—the agreements “do not entail ownership, lease or concession”. Such was the case of the communities of San Miguel, Centro Uno and El Limón: despite having cooperation agreements and forest concessions, they were displaced from their lands, which are now control points for the army and CONAP.

These agreements are framed within the policy on Human Settlements. The concept of “human settlements” refers to communities in a way that confines them to live in precarious conditions, or to be displaced without state institutions having the obligation to relocate them. “In 2004, I was involved in drafting the policy on Human Settlements. We tried to coordinate activities and determine under what conditions communities could remain. But the adoption of this policy was useless, because ten years went by and the Guatemalan State ignored it. This is why we currently have a new crisis”, says Laura Hurtado.

“CONAP's agreements with communities only benefit the State. Any violation of the agreements by the communities places them at risk of expulsion. Peasants communities cannot grow food or own livestock, so their means of survival are being taken away from them”, says Luis Solano, a Guatemalan researcher who has focused his study on Petén for decades.

According to press releases from human rights defenders and community organizations in Petén, “a fair agreement between CONAP and the communities would have three objectives: First, it must be legitimate for the people involved; therefore it will be signed after a real consultation, so as to include our communities' needs and demands. Second, the agreement should represent a balance between the interests of the State and the interests of our communities. In contrast to the unequal terms that prevail in the Cooperation Agreements, points of agreement that are advantageous to both parties shall be sought. Finally, the agreement will lead to legal certainty over the land, with the aim of protecting and recovering the environment. In this recovery process, our communities will be allies, rather than being stigmatized”.

On November 4, 2016, the Presidential Dialogue Commission officially established a High-Level Round Table between the Guatemalan State and the communities of Laguna del Tigre and Sierra Lacandón. However, the government has continued its policy of accelerating evictions of communities through judicial proceedings steered by the Public Ministry and CONAP—which contradicts its official position of seeking a peaceful solution to the land conflict.

After the alternative proposal was presented, a dozen meetings were held with the objective of reaching agreement on the rules that would govern the round table for dialogue—which would be established in an agreement signed by the communities and the State.

According to spokespersons from the peasant movement, the alternative proposal was just a starting point, “which failed because the government did not have the capacity, or the will to continue with the dialogue process. On the contrary, the criminalization of communities increased. The government continued spreading unfounded accusations that we are terrorists and drug traffickers”, say spokespersons from the organized communities. Avispa Midia contacted them after a series of community protests to demand restitution of the community of Laguna Larga.

According to a community press release, on March 21, 2017 one of the last meetings took place, wherein they confirmed the Guatemalan State's lack of political will. A day later, on March 22, personnel from the Guatemalan Army, DIPRONA and CONAP entered the work area of the La Mestiza community in the PNLT, with the intention of arresting the community members present. “Security agents stated that they were there to protect US citizen, Roan Balas (director of Wildlife Conservation Society in Guatemala), who was present at the time and claims to own those lands”, informed the Guatemalan media.

“Thereafter came the state-driven eviction of Laguna Larga, and that's when the “good faith” in the negotiation broke down. They kept inviting us, but it was a strategy to wear us down; because the officials never really discussed our proposals at the round tables,”

SAY COMMUNITY MEMBERS.

“Our proposal is lawful and is in demand of our rights. It is based on human rights, environmental protection, the political constitution of our country and international treaties. The government's silence is further evidence that we must follow through with our claim against the Guatemalan State before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR)”, reported community organizations, in response to the government's official position that has blocked dialogue over months.

In August 2017, the IACHR made a visit to the encampment of displaced persons of Laguna Larga, and in September issued precautionary measures regarding the rights to life and integrity of the evicted population.

Despite these recommendations, the Guatemalan government has been consistently denounced for not complying with its legal obligations. Officials make visits to the encampment on the border with Mexico—visits that are pointless because they go without medical personnel. There are even indications that the Land Fund is making displaced people sign individual requests for land, despite the fact that the demand is for collective restitution.

“The State is not complying with any of the precautionary measures that the IACHR granted to all inhabitants of Laguna Larga, who are surviving due to the support of their own community members and human rights organizations from Mexico and Central America”, said spokespersons for the peasant movement, who requested to remain anonymous to avoid retaliation.

Even so, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) in Guatemala—which is the obstacle to dialogue on the side of the State—is attempting to mediate the conflict. UNDP also finances PES conservation projects throughout the country.

“On June 27, 2018, we were summoned to meet with UNDP representatives in the capital. We have previously requested information from them, and asked them if they were financing carbon projects in Petén. The United Nations also sat down with state institutions in meetings to discuss modifications to the protocols on international standards on displacement; Guatemala has committed to complying with these protocols”.

This strategy is part of UNDP's investments in strengthening the “institutional framework for dialogue and socio-environmental conflict management in Latin America”. It is part of UNDP's actions to consolidate safeguards (measures to anticipate, minimize, mitigate or otherwise treat the adverse impacts associated with a given activity), which will allow for the implementation of more REDD+ projects in Guatemala.

“It is necessary to support the operations of institutions through the use of alternative dialogue mechanisms, with strategies based on the monitoring, prevention and analysis of complex problems. This should be done in such a way that parties can come to agreement upon the proposed demands, with the state obligations and company commitments that those entail”, said Rolando Luque, former head of the National Office of Dialogue and Sustainability in Peru. Along with officials from various Central American countries, Luque participates in United Nation workshops focused on conservation policies.

“We made a simple request to UNDP, that in the meeting with the State, nothing be done behind the communities' backs. If they are developing a protocol, we are requesting to participate, because they have an obligation to inform us of what they are doing”, claimed community organizations after recent events.

“We resist the farm, the environmental institutions and the transnational corporations that take away life”. Rocío García recalls, word for word, this phrase that she heard during her work in Izabal department—another region where plans to commodify nature are being implemented.

“...because they always dispossess peasants in the same way; they leave them without their means of livelihood and try to suppress their organizational practices and their relationship with nature. This is why communities see all these projects as another form of dispossession”, the Guatemalan anthropologist adds.

“I believe in conservation, but it must recognize the rights of communities and the possibility of their development”, says Laura Hurtado, director of Action Aid Guatemala. According to studies by her organization, “the best conserved areas are where communities are present, especially indigenous communities. Conservation has been promoted here in a completely incorrect and ineffective way. They are still in conflict with the communities, and they are not stopping the illicit activities that are plundering nature”, reflects the researcher.