Translated by Martha Pskowski prepared this article for publication in English.

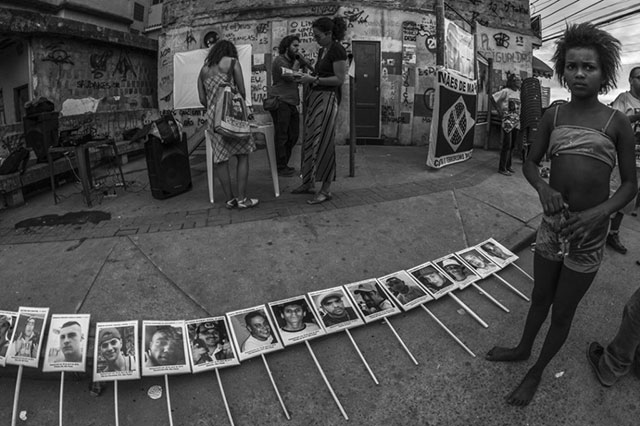

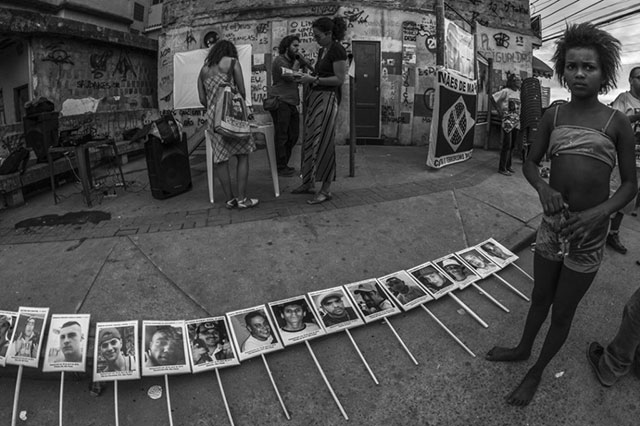

At least 77,206 people have already been displaced from Rio de Janeiro as the city prepares to host the Olympic Games on August 5-21, and police raids -- predominantly against Black youth in favelas and working class neighborhoods -- have intensified.

According to Larissa Lacerda, a member of the Rio Cup and Olympics Popular Committee, since the start of 2016, police raids in the favelas have provoked mass killings of poor, Black youth. Lacerda's organization is a collective that brings together unions, NGOs, researchers, students and impacted communities. She said she expects the situation to only get worse in the final days before the start of the Olympic Games, just as abuses worsened before the Panamerican Games and the World Cup.

"We are seeing an increased militarization of the city, in the context of a violent and racist security policy that particularly impacts Black youth who live in working class neighborhoods and favelas," Lacerda told Truthout. "These youth are murdered on a daily basis by police. But everyone is impacted by these policies that are based in fear, that create walls, both visible and invisible, and promote the social and spatial segregation of the city, and the increasing criminalization of social movements."

The Olympic Games in Rio de Janeiro will be the first Olympics to be held in South America specifically and only the second Olympic Games to be played in all of Latin America (with the first being in Mexico in 1968). Rio's transformation began with the World Cup in 2014. The projects undertaken for the World Cup -- including modernizing sports facilities, new transportation infrastructure, urbanizing marginal neighborhoods, and the restructuring and beautification of public spaces -- supported Rio's bid to become the host of the Olympic Games as well.

Since Rio de Janeiro was selected as host, mass media, politicians and various analysts have emphasized the benefits of increased investment in the city. In contrast, activists and social organizations have decried the mega sporting events as a direct attack against the most vulnerable sectors of Brazilian society.

Displacement and Police Raids

The Rio Cup and Olympics Popular Committee has reported that at least 22,059 families -- in total 77,206 people -- were displaced in Rio de Janeiro, between 2009, when Rio was chosen as the Olympic host, and 2015.

While the government avoids providing official statistics about sporting events, based on research in their communities and state statistics, the Popular Committee estimates that at least 4,120 families have been displaced and at least 2,486 more are at risk of displacement due to the infrastructure projects required for the Olympic Games.

The majority of displacement takes place in neighborhoods where real estate speculation has led to big returns for investors. In the past three years, the value per square meter of real estate in Rio de Janeiro has increased on average 29.4 percent, but there are some parts of the city, such as the Vidigal favela, where it has gone up as much as 481%. Of Rio de Janeiro's 11.8 million residents, between 1.5 to 2 million are spread between 900 to 1,000 favela neighborhoods. The favelas are settlements characterized by informal buildings, low-quality housing, limited access to public services, high population density and insecure property rights.

"The relocations related to the Olympic Games have affected thousands of families through coercion and institutional violence, gravely violating human rights,"

SAYS THE POPULAR COMMITTEE'S REPORT.

Brazilian authorities, to guarantee their bid for the Games in 2009, promised improved public security. According to the Brazilian government, public security planning began with the Panamerican Games in 2007 and the 2014 World Cup.

Youth are murdered on a daily basis by police.

Meanwhile, an Amnesty International report, "Violence is not part of this game! Major risks for human rights violations in the 2016 Olympic Games," warns that Brazilian authorities and the Olympic organization have put into practice the same security policies that led to an increase in murders and human rights violations by security forces since the 2014 World Cup.

Since 2009, police have killed 2,500 people in the city. "Justice was served in a small fraction of these cases," argues Atila Roque, Executive Director of Amnesty International in Brazil. The vast majority of the victims have been Black youth in favelas and working class neighborhoods.

Authorities recently announced that close to 65,000 police officers and 20,000 military troops will take part in security operations during the Olympics, making it the largest operation in Brazilian history, according to Amnesty International. The plan foresees part of this security force carrying out raids in the favelas. In the past year there have been high rates of human rights violations in the lead-up to the Games, with continued murders of youth in the favelas.

"Social Sanitization"

Since 2011, to prepare the city for mega sporting events, what Lacerda terms "social sanitization" operations, including clearing homeless children and youth, have taken place in areas in the city with tourism potential.

"In spite of the difficulties in obtaining specific statistics, reports have increased from youth and also adults who live in the streets," explains Larissa Lacerda.

The UN Committee on the Rights of Children, in its 2015 report on issues facing youth in Brazil, denounced the government initiative to "clean up" the city for the 2016 Olympics and issued the following call: "The Committee is very concerned with the high number of children living in the streets who are vulnerable to extrajudicial killings, torture, forced disappearance, recruitment by criminal groups, drug abuse and sexual exploitation." The committee also indicated it is necessary to promote laws against arbitrary detention of youth in the streets.

A Failed State

A wall in a favela in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. (Photo: Aldo Santiago)

A wall in a favela in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. (Photo: Aldo Santiago)

There is less than a month until the Olympics begin and Brazil is in the midst of a political and economic crisis, following the Senate decision to suspend president Dilma Rousseff for 180 days. Many people in Brazil and internationally consider Rousseff's ouster a coup d'etat. During the 180-day period she will be investigated for manipulation of public funds between 2014 and 2015.

"Rio de Janeiro is in the midst of a social and economic chaos," says Felipe Araújo, a resident of the Banqu neighborhood and researcher at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro. "Professors in the state system and at two universities have been on strike for more than three months. Teachers' salaries are frozen. Students continue to mobilize and demonstrate solidarity, despite the repression they have faced. The civil police are striking over their salaries and a lack of infrastructure, and the health system is in a serious crisis."

Meanwhile, Michel Elías Temer, of the Brazilian Democratic Movement Party (PMDB), affirmed on the day he assumed the presidency that the Olympic Games are an opportunity that "will improve the image" of Brazil and will contribute to "the international positioning of our economy."

The governor of the state of Rio de Janeiro, Francisco Dornelles, decreed a public emergency in the state's financial administration: The state was no longer able to maintain public services like health, transportation and education. Temer's interim government approved on June 22 a sum of $895 million for security and the completion of a subway line to connect visitors to the Olympic venues.

"The priority is not the people and their quality of life, but these big events, which in reality are a way to justify the flow of public resources for construction, favoring the contracting companies and a supposed growth in the tourism sector. In practice, this does nothing to help poor people, because all of the income is concentrated in big companies,"

SAYS ARAÚJO.

In terms of public security, it is important to mention that Brazil does not have riot police. It is the military that is sent to the streets to contain social discontent. Brazil's military structure was inherited from the coup d'état in 1964 and leaders were trained according to US and French military doctrine. This repressive and abusive legacy is on display today.

The United States suggested anti-terrorism security measures to Brazil, which appear to have been very influential in mega sporting events, such as the World Cup and the Olympics.

In 2010, under former President Luiz Ignacio Lula da Silva, Brazil signed a cooperation agreement with the United States which allowed for the US company Academi, previously known as Blackwater, to train the military police to prevent terrorist activities during the World Cup and the Olympics. Even though during the World Cup there were no terrorist attacks, in the Olympics the interim president is adopting the same discourse.

Unfulfilled Promises

A favela in Rio de Janerio, Brazil. (Photo: Aldo Santiago)

A favela in Rio de Janerio, Brazil. (Photo: Aldo Santiago)

The state's expressed motive is security, which has justified increased segregation of rich and poor in the city. Yet the Popular Committee shows in its report that the authorities are not complying with the majority of its promises to improve quality of life in the city.The projects that they are carrying out lack a basic respect for human rights.

Rio de Janeiro's government promised, for example, a "revolution in public transportation" in the infrastructure projects for the mega sporting events. However, the Popular Committee shows that the enormous investment in public transportation is distributed unequally. Investment only benefits a small portion of the population, concentrated in the rich neighborhoods of the city. Meanwhile, transportation lines that connect the rich neighborhoods with poor neighborhoods have been cut.

Working conditions have also suffered. For example, the Popular Committee denounces the repressive measures the government has taken against street vendors. This is due in large part to the construction of exclusive commercial zones, promoted by FIFA and its sponsors, surrounding the sports stadiums.

Another serious human rights violation, reported by the Public Labor Ministry of Rio, was carried out by Brazil Global Services, one of the construction companies contracted to build the Olympic Village. The company held 11 workers in conditions that the Public Prosecutors office compared to slavery. They were held in a house that was infested by cockroaches and rats and reeked of backed-up sewage.

According to the Committee report, since the selection of Rio to host the Olympics, environmental protection has been lauded as an important component of the construction projects. However, among other damaging projects, the Transolympic Via, which was built for the games, resulted in the destruction of 200,000 square meters of the Atlantic Forest. These projects violate the same environmental laws that in other instances have been used to justify the violent expulsion of entire communities in the name of conservation and to combat global warming.

According to Larissa Lacerda, the Olympic Games' legacy in Rio de Janeiro will be an even more segregated and exclusionary city. "Olympic City's design was premised on the deepening of socio-spatial inequalities, and it was built on a foundation of a policy of 'cleaning up' the city," she said.

Published in ⇒ Trutout

A wall in a favela in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. (Photo: Aldo Santiago)

A wall in a favela in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. (Photo: Aldo Santiago) A favela in Rio de Janerio, Brazil. (Photo: Aldo Santiago)

A favela in Rio de Janerio, Brazil. (Photo: Aldo Santiago)